The Government of Ireland Act 1920, which was responsible for partitioning this island, was introduced by the British government to solve the ‘Ulster Question’ and not the overall ‘Irish Question ‘ – which it did anything but solve.

Similarly, there is a danger that the recent Safeguarding the Union deal, in attempting to solve the ‘DUP Question’, might contribute to undermining stable politics in Northern Ireland.

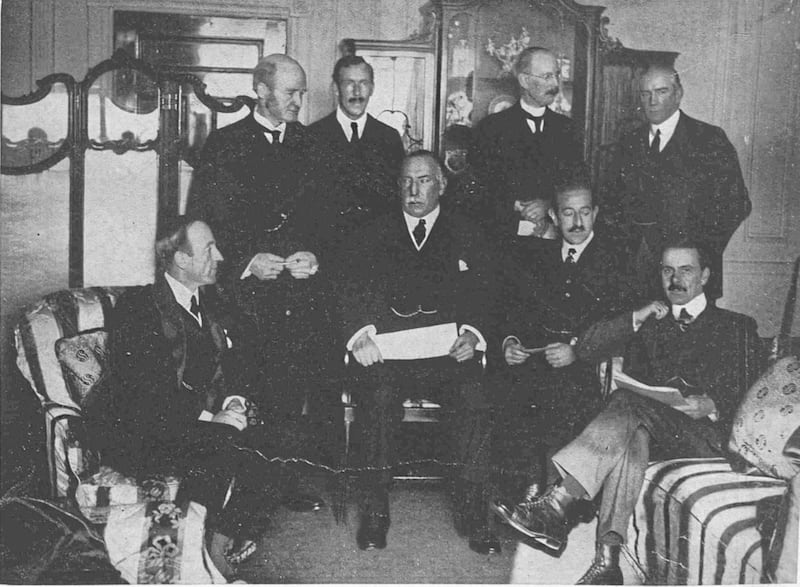

The committee established by British Prime Minister David Lloyd George to draft the Government of Ireland Bill was unionist in outlook. There was no nationalist representation whatsoever, nor was the advice of any nationalists sought during its drafting. James Craig and his Ulster unionist associates were the only Irishmen consulted. To ignore and then impose a solution on the citizens of Ireland demonstrates that the British government’s aim was to secure an agreement acceptable to Ulster unionists and no-one else.

Partition through the Government of Ireland Bill was not introduced by an impartial British government to solve the incompatible ethno-religious divisions in Ireland. As with other partitions it was involved in, the partition of Ireland was an attempt to extend the lifespan of the British Empire.

By offering nationalists far less than they demanded, and Ulster unionists far more than they sought, the bill clearly had only one audience in mind. With Sinn Féin in the ascendancy in the south and west of Ireland, the British government knew the legislation was unenforceable outside of Ulster. It was never the intention to do so.

- UK Government Command Paper: What’s in the Donaldson deal?Opens in new window

- Red, white and blue command paper seeks to restore unionist veto at Stormont – Brian FeeneyOpens in new window

- Heavy with spin, jaundiced and gratuitously insulting to non-unionists, the command paper is window dressing - Deirdre HeenanOpens in new window

Unsurprisingly, the Government of Ireland Act was rejected by all shades of nationalism, by southern unionists and opposition parties in Westminster. The Manchester Guardian said: “An act which should have been an act of conciliation and friendship has taken on the guise simply of another exercise of power.”

The Government of Ireland Act reminds me of the 2020 Trump administration’s plan “Peace to Prosperity: A Vision to Improve the Lives of the Palestinian and Israeli People”, authored by a team led by Trump’s son-in-law Jared Kushner. In having no input to a one-sided plan that would have had huge consequences for them, the Palestinians rejected it. While Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu declared it “the deal of the century”, Palestinian opponents dubbed it “the fraud of the century”. Despite the arrogant posturing of Kushner, his agreement was of course doomed to failure.

For the British government to negotiate exclusively with the DUP following the Windsor Framework in March 2023 poses similar problems. The government was, of course, limited in what it could grant the DUP, given its agreement with the EU – certainly not enough to meet all of its seven tests. The one-sided negotiations, however, should never have happened in the first place and, as Professor Deirdre Heenan stated in this paper on Monday, it “sets a very dangerous precedent”.

While the agreement has not been outwardly opposed by most stakeholders, many of whom were just exhausted and desperate for Stormont to function again, the language used and some of the claims made in the UK-DUP deal, by just appealing to one party in a divided society, have the potential to cause problems in the long term. Interestingly, the SDLP was the only party that did raise objections at the outset, with Sinn Féin too excited about having the First Minister post to express any concerns before Stormont was up and running again and Michelle O’Neill was safely in office.

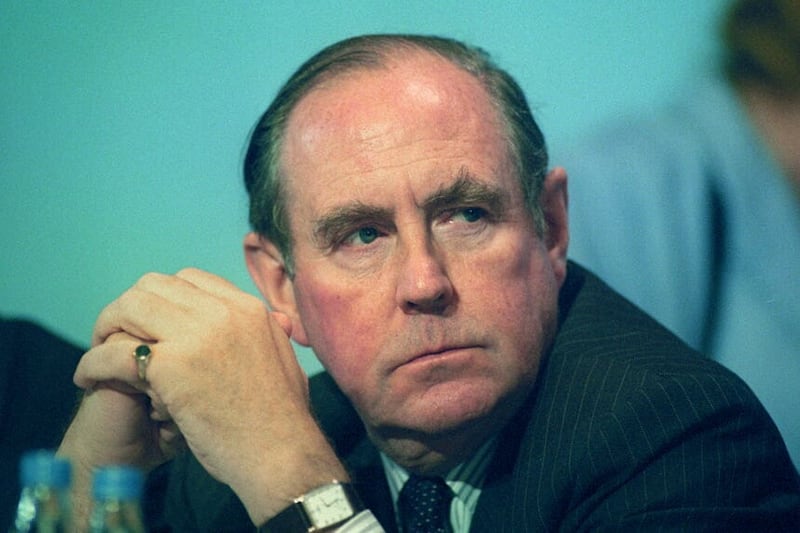

The deal reflects a further manifestation of a change in British government policy towards the north, one far removed from Peter Brooke’s claim in late 1990 that it had “no selfish strategic or economic interest” in Northern Ireland. Brooke’s comments at the time helped in no small way to pave the path for peace, culminating in the signing of the Good Friday Agreement eight years later. This perceived “rigorous impartiality” of the British government, so crucial for agreement to be reached then, now seems a distant memory.

Aside from the blatantly divisive title of “Safeguarding the Union”, the deal outlines how the British government will scrap all legal duties relating to the “all-island economy”, something it recognises as “one of the key concerns for unionists”. Advocating for Northern Ireland’s place in the union, the government claims that its “future in the UK will be secure for decades to come and as such the conditions for a border poll are unlikely to be objectively met”.

Speaking in the House of Commons shortly after the deal was published, Secretary of State Chris Heaton-Harris claimed that a vote for a united Ireland “absolutely depends on the consent of both communities”. That same day he admitted to a “GCSE-level knowledge of unionism”.

Wilful ignorance of their brief appears to be a badge of honour for many of the appointees to this post under this Tory government. Judging by his remarks on the requirements needed to call a border poll, he does not even have a GCSE-level knowledge of the Good Friday Agreement, which clearly states a poll will be called by the Secretary of State “if at any time it appears likely to him that a majority of those voting would express a wish that Northern Ireland should cease to be part of the UK and form part of a united Ireland”. Consent of both communities is not required. Scarily, he gets to decide when the conditions are right for a border poll to be called, an anomaly in the Good Friday Agreement that will become more apparent in the future.

There is a danger that the Safeguarding the Union deal, in attempting to solve the ‘DUP Question’, might contribute to undermining stable politics in Northern Ireland

It is not surprising that this jingoistic Tory government would loudly herald its unionist credentials, but it looks like nationalists will get little comfort from Labour too, who are likely to form the next British government later this year. Its leader, Keir Starmer, has claimed he would campaign against a united Ireland. Speaking to Sky News recently, the Labour Shadow Economic Secretary Tulip Siddiq, demonstrating about as much knowledge of the north as Karen Bradley did, when pressed if Labour would support a united Ireland, said the party wants it “to stay as it is”. The party that co-signed the Good Friday Agreement has also abandoned its commitment to “rigorous impartiality”.

While the UK-DUP deal is, of course, not as far-reaching as the Government of Ireland Act 1920, with the changes it provides already largely catered for under the Windsor Framework, the language used in this agreement, another one-sided one, is extremely divisive and further divorces the British government from its commitments to the Good Friday Agreement.