MOST people would agree that there will be a border poll in the not-too-distant future. There still is some debate on when the conditions are likely to be met for the British Secretary of State for Northern Ireland to trigger a border poll.

Drafted in the 1998 Good Friday Agreement for the Secretary of State alone to call one, the criteria required for him or her to do so is a little vague. And given the deep distrust many nationalists have of previous British administrations, there are fears that the British government cannot be relied upon to act fairly in calling for such a poll.

There are also concerns that, as has happened at the time of Ireland's partition, the goalposts will be moved and that the requirement of '50 per cent, plus one' supporting unification in both Irish jurisdictions, as also conveyed in the Good Friday Agreement, will no longer suffice.

The late Seamus Mallon's comments that there should be consent for Irish unification within both communities were rightly criticised as granting a permanent veto to unionists and adding more weight to a unionist's than to a nationalist's vote. Once a unionist consents to a united Ireland, surely that person is no longer a unionist, thus allowing, under Mallon's suggestion, all remaining unionists, regardless of their dwindling numbers, to block a unification path indefinitely.

Nationalists will also have noted with trepidation recent attempts by unionists to move the goalposts, such as Ian Paisley Junior's introduction of a referendum supermajority bill at Westminster and suggestions within unionism that Northern Ireland should remain or not within the UK based on a UK-wide vote.

Some of the sharpest criticisms came on the back of political scientist Professor Brendan O'Leary's recent comments that Irish unification would be more successful if there was, what he called, "losers' consent".

Read more:

Why did the Free State impose a hard land border in Ireland 100 years ago?

Partition at 100: Brexit trade barriers an echo of the past and the 1923 customs barrier

Partition: The Free State's abandonment of northern nationalists

From listening to O'Leary's recent comments and from reading his book Making Sense of a United Ireland, it is clear he is not arguing that "loser's consent" must happen for a united Ireland to come into being. He insists Irish unity must be based on a majority of votes in both Irish jurisdictions, but that the success of unification would be greatly helped by unionists accepting the result, a wholly reasonable assertion to make.

Yet, some nationalists felt this was another attempt to introduce a unionist veto on Irish unity, another attempt to move the goalposts again. While ill-founded in this instance, Irish nationalists', particularly northern nationalists', fears of decisions being made always to their detriment are deep rooted. We need to look at how Ireland was partitioned to understand where much of these fears stem from.

As the Decade of Centenaries commemorations have shown us, a lot happened in Ireland from the introduction of the Third Home Rule Bill in 1912 to the shelving of the Boundary Commission report in 1925, resulting in Northern Ireland's territory remaining unaltered.

When partition was first considered as a realistic option to overcome the impasse created by Ulster unionism's opposition to home rule, initially the plan was for the temporary exclusion of some Ulster territory from a home rule parliament. By the time the border was essentially finalised in 1925 to a permanent two-thirds unionist majority for six Ulster counties, the goalposts had been moved to an entirely different playing field, such was the skewing of decisions in favour of Ulster unionists.

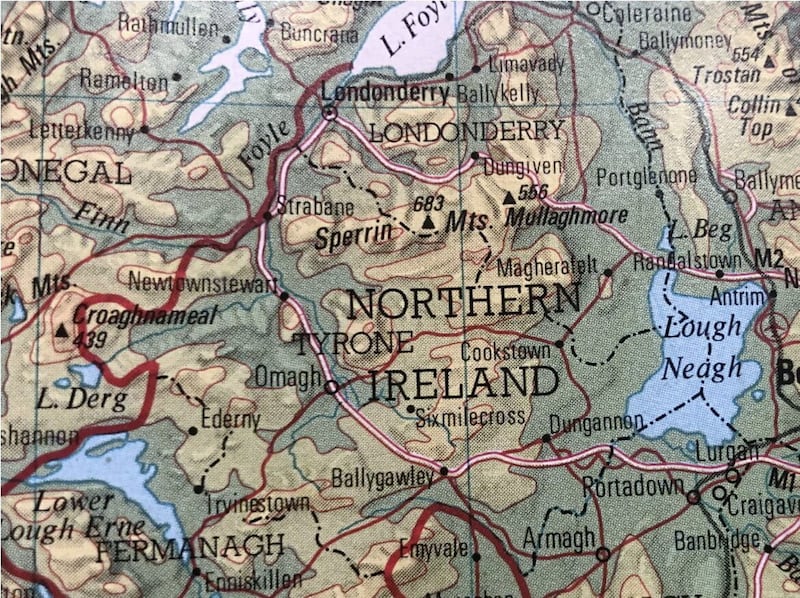

While John Redmond's Irish Parliamentary Party reluctantly conceded to the temporary exclusion of four counties from a home rule parliament, this was soon changed to six, with Tyrone and Fermanagh that consisted of Catholic majorities, included in the exclusion. Ulster nationalists voted in June 1916 to temporarily exclude six counties, however, the British government almost immediately changed the demands, insisting that their exclusion would be permanent

Nationalists were not even consulted on the framing of the scheme that led to Ireland's partition, the Government of Ireland Act 1920. The British government initially planned for the nine counties of Ulster to be included in Northern Ireland, claiming this would lead to eventual unity and that "the two religions would be not unevenly balanced in the Parliament of Northern Ireland".

This was soon changed too after Ulster unionists demanded the new devolved entity consist of six counties to ensure that a permanent Protestant majority would prevail.

The Government of Ireland Bill was further amended just to accommodate Ulster unionists. The amendments accepted included the limiting of the powers of the Council of Ireland from the Bill's original draft, and the ability to remove the Proportional Representation (PR) system of voting after three years, measures Ulster unionists sought and were granted to make partition more durable, more permanent.

Some Ulster unionists at the time, and since then, have claimed that they made a big sacrifice by conceding to a devolved government for Northern Ireland, and not remaining wholly governed by Westminster, as was their preference. In reality, it was not a sacrifice: it was highly advantageous for unionists.

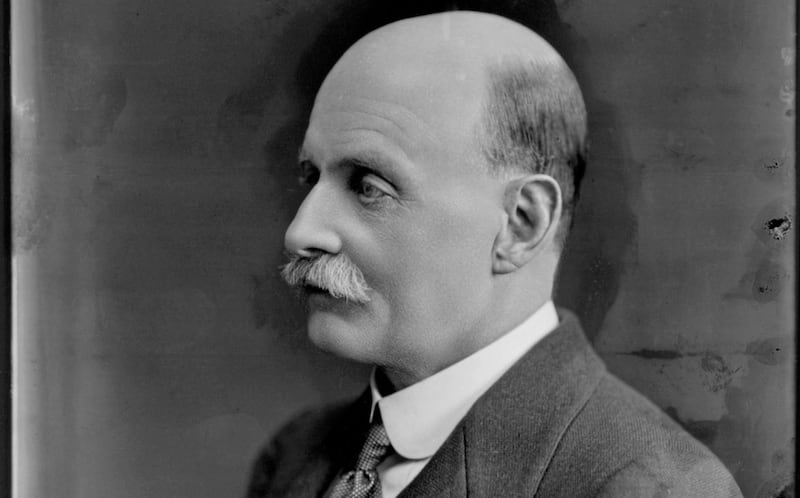

James Craig's brother, Charles, began to see the great benefits Ulster unionists would garner from having their own parliament, claiming: "The Bill practically gives us everything that we fought for, everything we armed ourselves for".

The Northern Ireland government, once in power, was soon able to disregard elements of the Government of Ireland Act, including the removal of the PR system of voting for local elections in 1922 and the open flouting of the Act's anti-religious discrimination clauses, without any sanctions from the British government.

Believing the Ulster question was settled by the Government of Ireland Act 1920, unionists were greatly perturbed by the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921, particularly by its boundary commission clause. Although Ulster unionists were not party to the Treaty, they were now obliged to adhere to its clauses. The boundary commission re-opened uncertainty and put Northern Ireland's future, at least significant parts of it, in doubt yet again.

While the boundary commission was viewed as a major concession to Sinn Féin, the details and wording of the clause agreed to in the Treaty proved to be disastrous for Sinn Féin and particularly for northern nationalists close to the border.

Although Sinn Féin floundered greatly by acceding to such a vague and ambiguous clause and by not insisting on similar terms for a boundary commission to the ones that had convened in post-First World War Europe, British governments were misleading, if not downright dishonest, in how the boundary commission was ultimately interpreted.

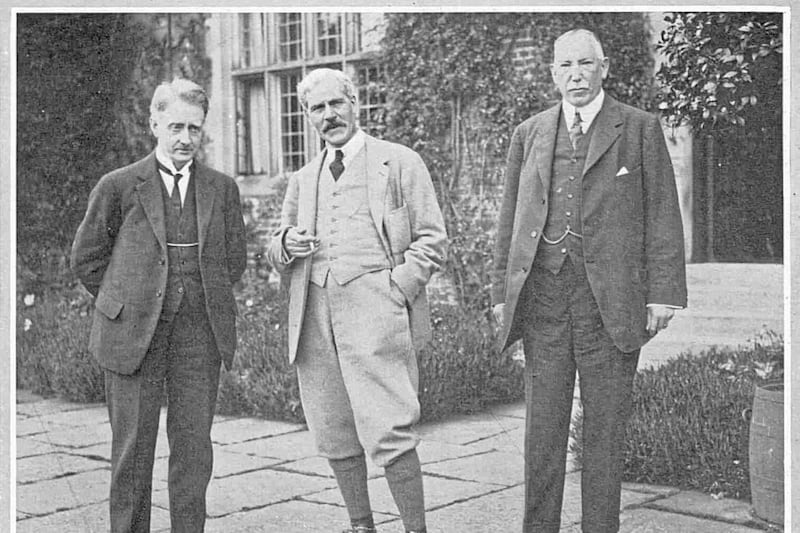

The judge appointed by the British government to chair the three-person boundary commission, was Justice Richard Feetham, a British-born South African-based judge with conservative political views. Unsurprisingly, all his interpretations and decisions favoured the unionist over the nationalist case.

In nationalist circles he became known as 'Feetham-Cheat'em'. He decided not to conduct a plebiscite, choosing instead to assume a quasi-judicial approach and ruling out wholesale transfers, disadvantageous to nationalists.

Feetham looked at economic conditions as they prevailed in 1924/25 and not how they were interpreted by the Treaty signatories in 1921, again disadvantageous to nationalists. In fact, Feetham refused to hear any evidence on how the Treaty signatories interpreted Article 12, despite its obvious ambiguities. This proved highly damaging for the nationalist cause.

Feetham decided that smaller units such as district electoral divisions, instead of large units such as entire counties, should form the basis of areas to be considered for transfer, also disadvantageous to nationalists. He also gave primacy of economic and geographic conditions over the will of the people, the primacy of the Government of Ireland Act 1920 over the Anglo-Irish Treaty, and that the Irish Free State could lose as well as gain territory, all decisions disadvantageous to nationalists. It resulted in the commission recommending minimal transfers to the Free State, but also transfers from the Free State to Northern Ireland.

Once this was leaked in November 1925 by the Morning Post newspaper, the Irish Free State government rushed over to London to have the report shelved, resulting in the border remaining as it was, as it does to the present day.

From 1912 to 1925, many decisions were made that resulted in the type of partition that was ultimately delivered. For northern nationalists, each step taken on the long meandering road to partition saw the goalposts move constantly, always to their detriment, resulting in what they believed to be a deeply unfair and immoral outcome.

While fears still exist that the same could happen again, and the path to Irish unity will be undermined by unfairness and the moving of goalposts to accommodate unionist demands, circumstances have changed considerably from 100 years ago.

The UK is in a far weaker political position now, as are Ulster unionists, and the terms as laid out by the Good Friday Agreement, an internationally recognised and respected agreement, are clear on what is required to bring about Irish unity.

:: Cormac Moore is author of Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland (Merrion Press, 2019).