IT is almost forgotten that the DUP boycotted the North South Ministerial Council (NSMC) in 2021 before it withdrew from Stormont in February 2022, also over the Northern Ireland Protocol.

The last time the NSMC met was in July 2021. The DUP has had a difficult relationship with it, with a Belfast High Court judge ruling that one of its Assembly ministers, Edwin Poots, acted unlawfully by not attending meetings with his Irish ministerial counterpart Charlie McConalogue.

Reticent of engaging in any north-south body, the DUP wishes to expand relations with other parts of the UK instead, as outlined by Sir Jeffrey Donaldson’s recent call for an east-west council.

Interestingly, the main opposition to the Council of Ireland, the first north-south body proposed after the partition of Ireland, was not from Ulster unionism, but from Sinn Féin.

Read more:

Cormac Moore: Nationalist divisions pose obstacle to united Ireland

United Ireland: How a border poll will be called - an explainer

Under the Government of Ireland Act 1920, a Council of Ireland was planned to be composed of 20 members from each parliament to look after areas of common concern between both jurisdictions. The British government claimed that the council would lead to "the peaceful evolution of a single parliament for all Ireland".

While Ulster unionists accepted the Government of Ireland Act and its Council of Ireland provisions, they sought to dilute its powers through amendments as the Bill made its way through Westminster for much of 1920. By the time it became an Act, the Council of Ireland had responsibility for railways, fisheries and contagious diseases of animals, but both parliaments, through identical acts, could delegate it with more powers at any time.

It is important to note that while Ireland may have been a member of the United Kingdom, it was, before partition, treated as a separate unit with many all-Ireland departments run from the Dublin Castle apparatus such as the Board of Education and the Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction.

The Council of Ireland provisions in the Government of Ireland Act should not, therefore, be seen as an enlightened piece of legislation aiding to unite Ireland when the Act itself was responsible in the first place for dividing it and the many all-Ireland departments in existence at the time.

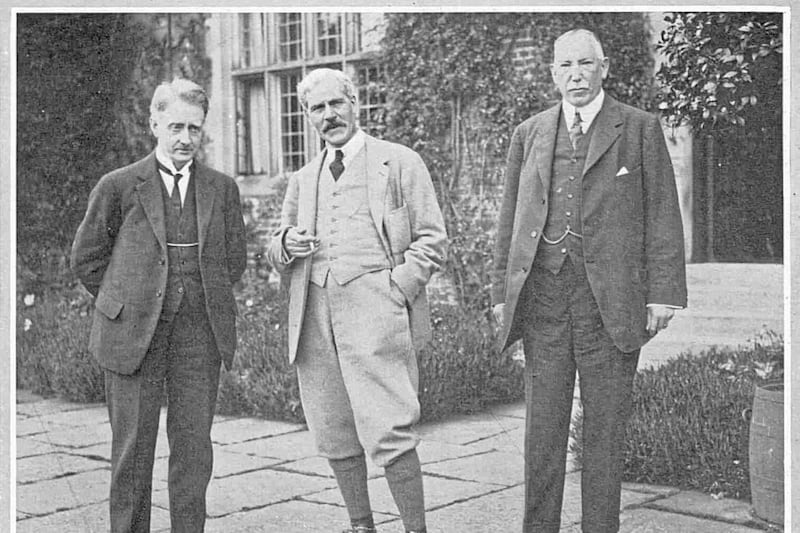

On becoming leader of the Ulster Unionist Council in February 1921, James Craig talked of using the Council of Ireland to address all-Ireland problems. He stated he was prepared to meet Sinn Féin leader Éamon de Valera through the council, whereby both men could "discuss all matters which were considered to be for the benefit of Ireland as a whole".

At the northern government’s first ever cabinet meeting on June 15 1921, Northern Ireland’s 20 representatives for the Council of Ireland were selected, led by Craig, with 13 from the House of Commons and seven from the senate.

The Government of Ireland Act 1920 was of course rejected by Sinn Féin who instead negotiated the Anglo-Irish Treaty of December 1921 with the British government. During the Treaty negotiations, Sinn Féin’s lead plenipotentiary Arthur Griffith criticised the north being offered 20 members on the Council of Ireland, the same as the 26 counties combined. Despite Griffith’s misgivings, the Council of Ireland was retained under Article 13 of the Treaty, with the Free State parliament empowered to elect its Council of Ireland members instead of the defunct Southern Ireland parliament.

The Free State provisional government showed no desire to make the Council of Ireland operational, with Michael Collins and Craig, in the first of their two short-lived pacts, of January 1922, endeavouring to find ‘" more suitable system than the Council of Ireland… for dealing with problems affecting all Ireland". Craig believed, in its proposed form, the council would be more of an irritant to both sides and suggested that it might be replaced by joint meetings of both cabinets.

The Council of Ireland was put in cold storage for five years in an agreement reached between the Irish Free State and British governments in late 1922. Three years later, in December 1925, having never convened, the council was disbanded in the tripartite agreement following the post-Boundary Commission debacle.

While it was considered an ‘irritant’ to the Northern Ireland government, the Free State government readily abandoned it. Due to the enhanced and independent nature of the Free State’s political status, the remit of the Council of Ireland had changed from dealing with all-island issues to ones just affecting Northern Ireland.

The Free State government ascertained this would have not helped towards unity, with Finance Minister Ernest Blythe claiming it would have done more harm than good as it would have acted "as a constant source of irritation to the Six Counties".

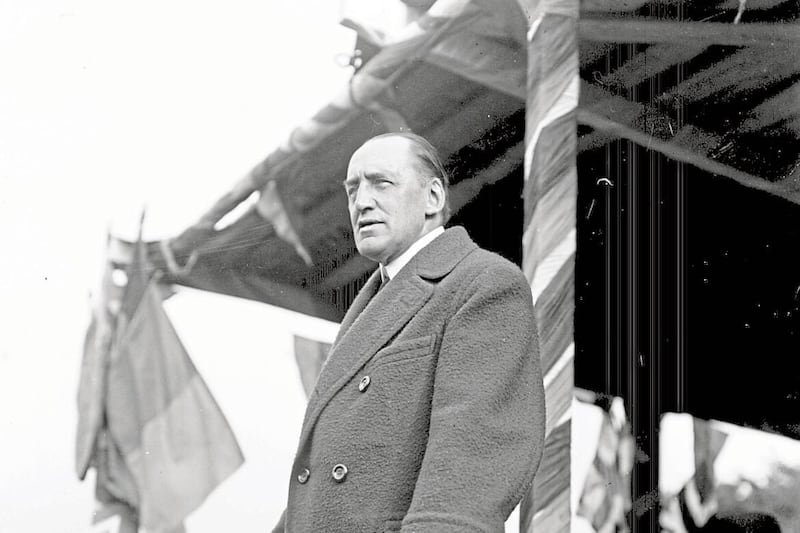

Mocking the Irish Labour Party leader Thomas Johnson’s ‘obsession’ with the Council of Ireland as a means to bring about Irish unity, Justice Minister Kevin O’Higgins viewed it as a trivial body that only deliberated over "thistle cutting" and "sheep dipping". He failed to add that the Council of Ireland could have increased its powers at any time and that perhaps the real reason behind the Free State’s government reticence towards it was that the Council of Ireland would have forced the Free State government to recognise Northern Ireland as a legitimate entity in a very public way.

In lieu of the Council of Ireland, Craig "suggested joint meetings of the two governments in Ireland 'at an early date' so that both governments could deal with charges brought by one against the other", to which Free State Executive Council president WT Cosgrave agreed – but both never met each other again. In fact, the next meeting between the heads of both Irish governments occurred 40 years later when Seán Lemass met Terence O’Neill in 1965.

When the Troubles broke out, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael-Labour Irish governments pursued a more active involvement for the Irish state in northern affairs, including by then not only support, but active pursuance of a Council of Ireland with executive powers.

A Council of Ireland was a key component, along with power-sharing, of the Sunningdale communique of December 1973 agreed between the Irish and British governments, as well as the Ulster Unionist Party, the SDLP and the Alliance Party. While the power-sharing executive met briefly, the Council of Ireland did not, and was one of the major reasons for the widescale unionist opposition to Sunningdale which resulted in its collapse by May 1974.

An iteration of the Council of Ireland concept, the North-South Ministerial Council, with real powers and not just ‘a chat show’, was insisted upon by Taoiseach Bertie Ahern in the negotiations that led to the 1998 Good Friday Agreement.

Now, the North South Ministerial Council, with a full-time secretariat headquartered in Armagh, is responsible for six implementation bodies including Waterways Ireland, InterTradeIreland and the Language Body, as well as overseeing six areas of co-operation between north and south, namely agriculture, education, the environment, health, tourism and transport. From 1999 to 2021, there were 26 plenary meetings between northern and southern ministers.

While the north-south features of the Good Friday Agreement do not capture the public imagination as other parts of the agreement do, and, as with the Northern Ireland Assembly and Executive, North South Ministerial Council meetings have been cancelled and boycotted at different stages, the work of the north-south bodies has continued and has significantly contributed to both jurisdictions, economically and socially.

They are a far cry from the ‘thistle cutting’ and ‘sheep dipping’ powers of the Council of Ireland as imagined by Kevin O’Higgins, as is the Irish government’s approach to and embracement of north-south bodies.