Being under siege, or at least the perception of being under siege, has been the default position of Ulster unionism for some time. This almost permanent state of facing down an existential threat has galvanised supporters over the years.

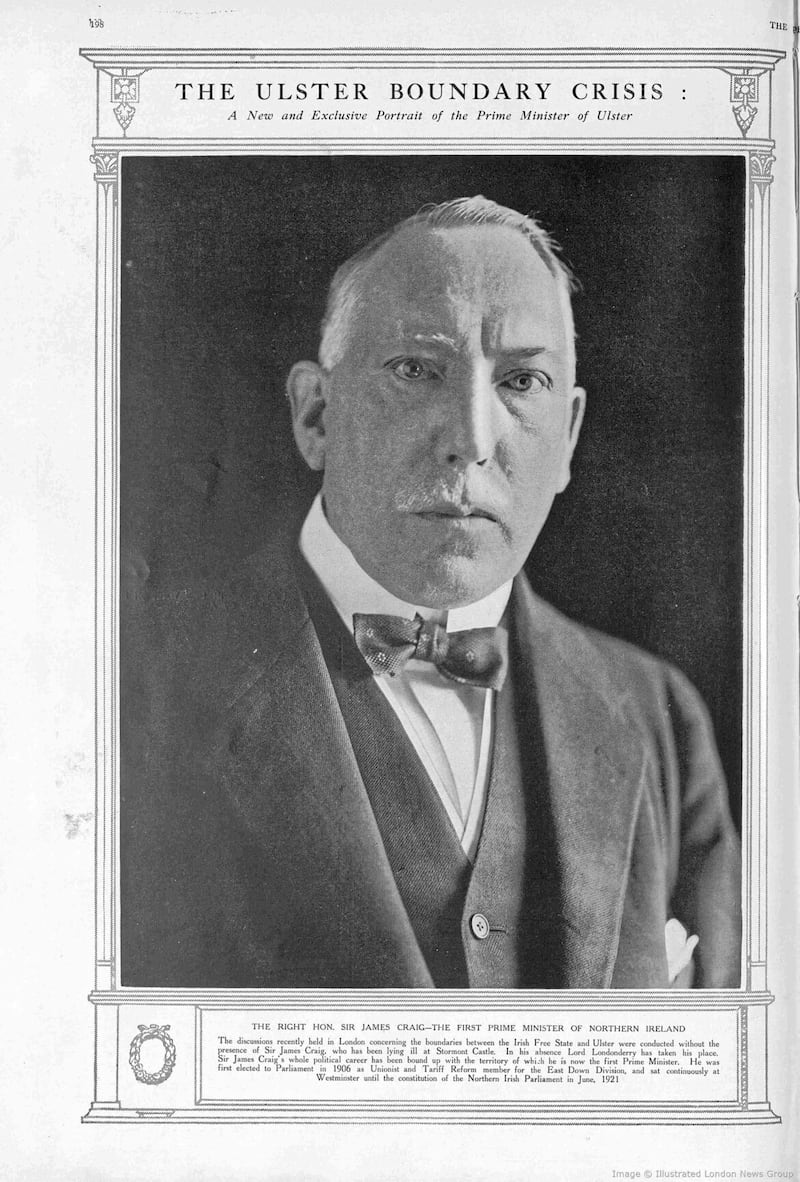

Edward Carson’s successfully-led campaign of resisting all attempts at being forced into a Dublin-run Home Rule parliament and James Craig’s (also successful) campaign of not giving an inch of northern territory to the Free State during the Boundary Commission crisis have provided inspiration to Ulster unionism ever since and in many ways shaped its strategies right up to the present day.

But while such inflexibility may have succeeded in the past, it will not today, as unionism finds itself in a far weaker position than ever before.

Read more:

- Partition: WT Cosgrave talked about united Ireland but wasn't serious about interests of northern nationalists

- Cormac Moore: Was Eoin MacNeill to blame for Boundary Commission's 'disastrous' outcome?

- Why did the Free State impose a hard land border in Ireland 100 years ago?

Unionists were able to resist all attempts to pressure them into a Dublin parliament during the third Home Rule crisis because of the substantial support they received from senior British, particularly Conservative, politicians. Although the Conservative Party used the crisis in Ireland to further its own ends, many were sincerely committed to the Ulster unionist cause, particularly its leader Andrew Bonar Law.

Even though Bonar Law was born in Canada, he was from an Ulster-Scots background, his father having been born in Coleraine, and was considered an ‘orange fanatic’. Unlike Boris Johnson’s commitment to the DUP that there would be no Irish Sea border under his watch, Bonar Law was not lying when he claimed at a large unionist rally in Blenheim Palace in July 1912 that if Home Rule was imposed on Ulster, he could "imagine no length of resistance" Ulster would go to "in which I should not be prepared to support them".

It was under his leadership that the Tories fused together Liberal unionists and Ulster unionists to form the Conservative and Unionist Party. Carson and Craig knew they could go to great and extreme lengths to resist Home Rule by the explicit support of the Conservative Party and the implicit acquiescence of the Liberal government, a lukewarm ally of John Redmond’s Irish Parliamentary Party at best.

After the First World War, the Liberal prime minister David Lloyd George, a brighter and more capable version of Boris Johnson, who wanted a deal on Ireland, any deal, as long as he made it, was constrained by the control unionist-supporting Conservatives had over his government.

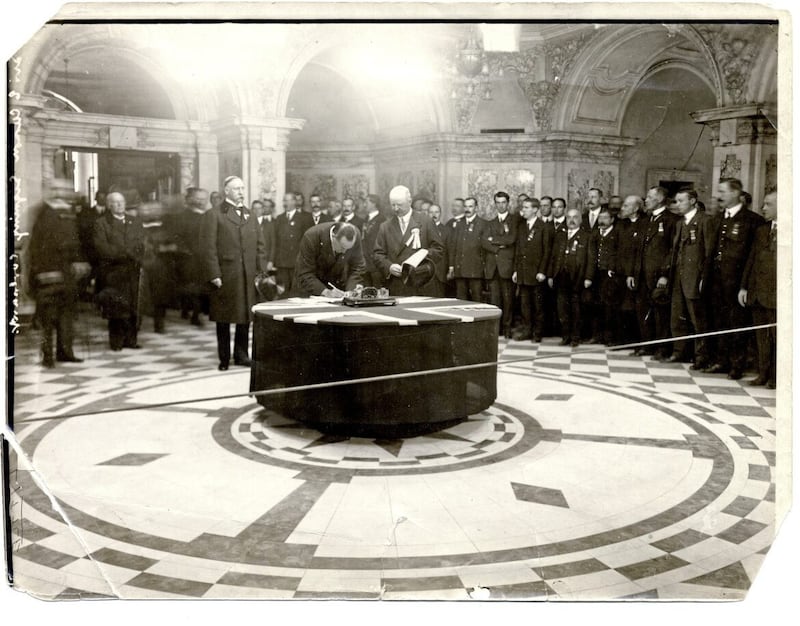

The main commitment of the Conservatives – who won 379 seats in the 1918 general election – was that there would be no coercion of Ulster into a united Ireland. This paved the way for the Government of Ireland Act 1920, partitioning Ireland in the sole interest of helping unionists.

Fast forward to today, and unionists find themselves short of allies in British politics, certainly allies who can further their interests at policy and legislative level. Most in Westminster now have little interest in and even less knowledge of Northern Ireland.

Demonstrating an enormous capacity for strategic blunder, the DUP did not make the most of its fortuitous position of holding the balance of power after the 2017 UK general election. Instead of accepting Theresa May’s deal which would have retained Northern Ireland’s trade position fully aligned with the rest of the UK, the party chose to ally itself with the Conservative’s European Research Group (ERG), with many quixotically hoping for a hard land border.

Jacob Rees-Mogg and Suella Braverman are no Andrew Bonar Law or Arthur Balfour. And neither are Sammy Wilson or Ian Paisley Junior a Carson or a Craig.

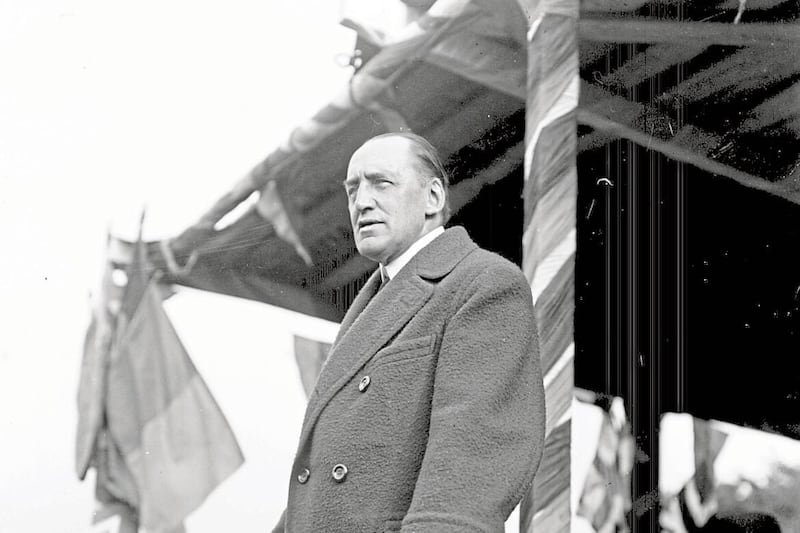

It is unlikely that Ulster unionists would have been as successful as they were without the leadership of Carson and Craig, the two towering figures in opposition to Home Rule and the two men most responsible for the establishment of Northern Ireland.

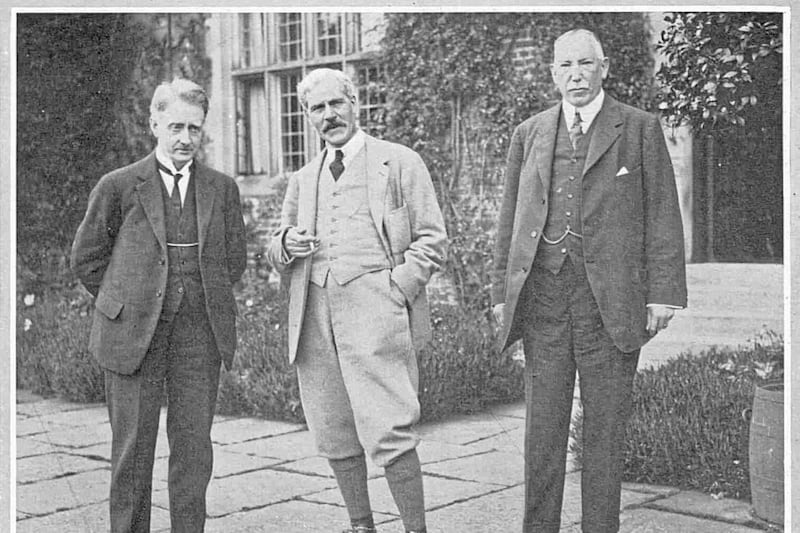

While Carson presented the public face, it was Craig who masterminded the Ulster unionist campaign against the third Home Rule Bill. Craig’s pragmatic and administrative skills complemented Carson’s charisma and power of oratory. Craig’s biographer St John Ervine claimed "effective apart, they were irresistible together".

Both were also deeply entrenched in British politics, and thus had a front seat table as Ireland’s future was being decided in Westminster. Carson was touted as potential leader of the Conservative Party after Arthur Balfour resigned in 1911 and served as a cabinet minister at different points in Lloyd George’s wartime government. After the First World War, Craig was in a unique position to influence British policy towards Ireland, serving in the British government from 1919 until 1921.

In his last role as Financial Secretary to the Admiralty, he was in effect the First Lord, as the office-holder Walter Long was too ill to carry out his duties. Craig was the main Irish person consulted on the Government of Ireland Bill, which allowed him to influence it in the interests of Ulster unionism. He was instrumental in ensuring that Northern Ireland consisted of six instead of the nine counties of Ulster and demanded from the British Government a special reserve police force for loyalists, the Ulster Special Constabulary.

Now, the party of Carson and Craig, the UUP, appears to be in terminal decline, while the largest unionist party, the DUP, seems to be leaderless and rudderless, too busy looking over its shoulders and allowing a blogger without any electoral mandate to dictate unionist policy.

Most distressing for unionists is how their position of dominance and strength has evaporated, a position gained by supportive British governments and strong, bullish leadership within.

The “permanent” majority is long gone, as is unionist monopoly rule, never to return. The tactics of Carson and Craig to resist all attempts at compromise can no longer be seen as strengths, they are now a sure-fire way to failure given the demographic make-up of the north today.

While many unionists still take solace in the days of the Solemn League and Covenant and “not an inch”, those days are over. As Lord Paul Bew recently pointed out: “Just being thran is not a political strategy”.

A totally new mindset is required if unionists are to have any chance of maintaining Northern Ireland’s position in the UK.