THE Ulster unionist opposition to home rule which ultimately led to the partition of Ireland was based not just on religious differences and concerns but also on real and perceived differences and concerns over issues such as identity, the economy and language.

Other than the issue of identity, most of the other arguments used to resist home rule have eroded over the last 100 years.

Religion and a united Ireland

Unquestionably, the largest division between Ulster unionists and Irish nationalists was over religion, with unionists believing their Protestantism would be supplanted in a home rule parliament dominated by Catholics.

Religious tensions were aggravated by two papal pronouncements published shortly before the introduction of the third Home Rule Bill in 1912. The first, the Ne Temere decree of 1908, declared that all mixed marriages not celebrated before a Catholic priest would be invalid. The second, Motu Proprio, Quantavis diligentia, issued in October 1911, forbade lay people from suing ecclesiastics in the law courts unless they had permission from their bishop. The two Vatican decrees were used extensively by unionists as a tool to oppose home rule, claiming it would lead to Rome rule.

Read more:

- DUP leader Sir Jeffrey Donaldson: No united Ireland in my lifetime

- Poll shows expectation of united Ireland within 10 years

- Carl Frampton: Assembly needs to return before any discussion on United Ireland

The Catholic Church went on to exert enormous influence and power over the Irish Free State. This influence has all but evaporated now, with Ireland becoming an increasingly secular nation. While the fears of unionists over religion were genuine and, in some cases, well-grounded 100 years ago, there now is little fear of being unable to enjoy full religious freedom in a united Ireland.

Many unionists at the time of partition, as well as most members of the British establishment, not only linked religion to national identity but to other characteristics too, many of them deeply offensive and supremacist towards Irish Catholics.

'Energetic' unionists vs 'lawless' Catholics

Northern unionists were characterised as industrial, business-like, pragmatic, energetic and law-abiding, with Irish Catholics perceived as possessing the opposite traits of being agrarian, unbusiness-like, superstitious, lethargic and lawless.

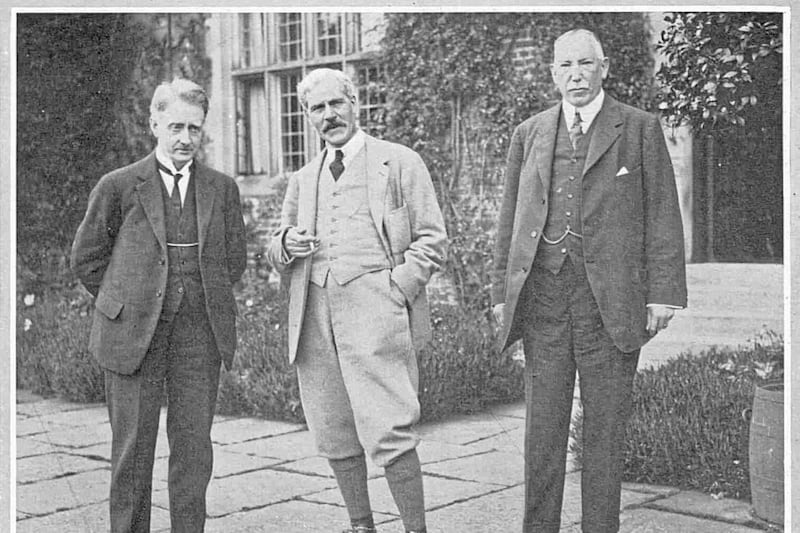

In 1918, one Tyrone unionist politician described the south as "barren, impoverished, badly governed and backward… pauperised owing to the incurable laziness of its people". The simian caricature of a ‘typical’ Irishman, drunk and violent, was much in vogue throughout Britain at the time. Andrew Bonar Law, Conservative British Prime Minister from 1922 to 1923, referred to the Irish as "an inferior race".

These feelings of supremacy were substantiated for many unionists by the economic miracle experienced by Belfast at the time. Although this came to a halt in the early 1920s as the shipbuilding and linen industries declined, the latter terminally so, and did not spread to most parts of the six counties that went on to form Northern Ireland, it provided ample proof to unionists that their future was better served remaining in the UK, with its large economy driven by its global empire.

The Irish state was impoverished for decades, torn apart by a civil war at its foundation, an agricultural economy dependent on Britain, scourged by emigration, seen by unionists as being ruled by a Catholic cabal who desired to turn Ireland into an Irish-speaking Celtic mystical land.

UK or united Ireland 'choice between civilisation and barbarism'

To internal critics of Northern Ireland in 1923, it was easy for Minister of Labour John M Andrews to patronisingly respond that "it was up to their people to remember when they were criticising them what they had saved them from. They had saved them from being submerged in the Free State… It was all too sad for words there". For some unionists, remaining in the UK or joining a united Ireland was "a simple choice between civilisation and barbarism".

Expressions and feelings of supremacy may still exist and perhaps Suella Braverman was pointing this out (even if she does not realise it yet) when she referred last week to marches in Northern Ireland as "an assertion of primacy". Thankfully such expressions hold little currency any more and are rightly condemned by most when they are dragged to the surface.

Brexit is often cited as a catalyst for a united Ireland but arguably a far greater driver for unity – the transformation of the south’s economy and society over the last 30-plus years – is mentioned far less frequently.

Read more:

- Patricia Mac Bride: Would we be better off in a united Ireland?

- Brian Feeney: United Ireland needed to end north's permanent state of crisis

- Alex Kane: A united Ireland is not the answer

In 1921, people from the UK earned more, lived longer, had access to better education and health resources. The introduction of the welfare state in the late 1940s resulted in free education and healthcare (through the NHS) and far superior pension and welfare benefits. While Northern Ireland always lagged behind other regions in the UK, there were few tangible attractions south of the border to entice people to advocate for unity.

Today's Ireland a strong, confident country

Today the Irish state is a confident country with a strong economy that compares favourably on most parameters to Northern Ireland and indeed to the UK overall. As columnists of this newspaper, Patricia Mac Bride and David McCann, have previously highlighted, wages and welfare benefits are higher in the south.

While it does not have free access to healthcare at the first point of entry for all, the healthcare system is teetering at the seams in the north, as it is throughout the UK. Although the healthcare system faces deep problems in the south, life expectancy is now higher than it is in the UK. In Ireland, the average life expectancy is now 82 years. In 1922, it was 57.

While economies fluctuate, it would take something seismic for the Irish economy to collapse to depths experienced before the 1990s – an act of national sabotage such as leaving the EU, perhaps. Even during the height of the late 2000s financial crash that afflicted Ireland more than most, it remained one of the richest countries in the world.

As the prospects for a border poll appear slowly on the horizon, those of us who desire a united Ireland can now confidently proclaim that unionist fears from a century ago over religion, the economy and society have eroded.

Being part of a united Ireland should now offer real improvements to the lives of people from Northern Ireland who could save themselves from an increasingly impoverished UK.