IN the years of Ireland’s partition, the Anglo-Irish War of Independence and subsequent civil war, Irish nationalism was riven with division and rivalry.

While the starkest example of this division was between pro- and anti-treaty Sinn Féin and IRA members, primarily over sovereignty issues, resulting in the cataclysmic civil war, there also were intra-nationalist divisions between republicans and constitutionalists and even between northern and southern nationalists, albeit the latter was rarely admitted overtly.

Although intra-nationalist rivalry is normal, particularly when seeking votes from the same pool of the electorate, a lack of unified approach within Irish nationalism towards partition, an issue all strains opposed, hindered its response to the division of Ireland. Unity within nationalism may not have prevented partition from happening but it could have mitigated against its worst excesses.

Ireland unification

Today, political parties who desire a united Ireland, north and south will need to work together, including by respecting each other’s differences, to achieve Irish unity.

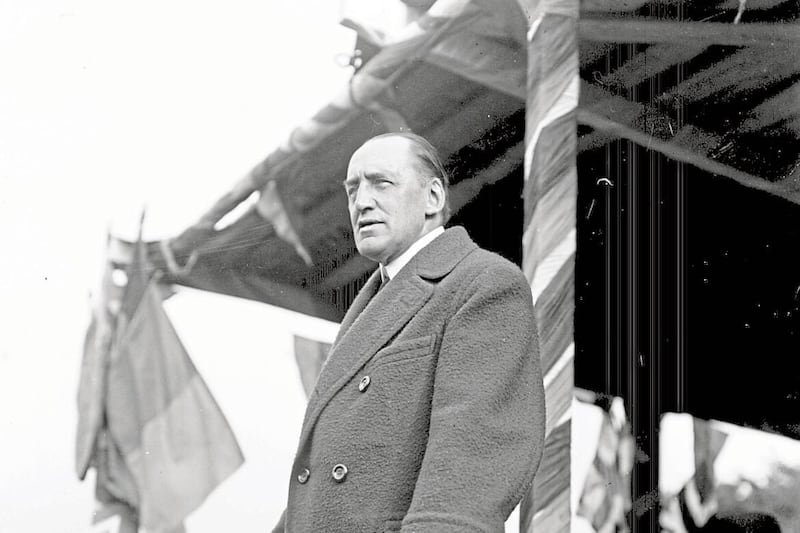

Recognising its political weakness in Ulster, Sinn Féin agreed to an electoral pact for the province with the Irish Parliamentary Party in the 1918 UK-wide general election. The pact worked for seven of the eight constituencies chosen, with the preferred nationalist candidate winning those seats. It collapsed in Down East when Michael Johnson refused to stand down in favour of the Sinn Féin candidate, Russell McNabb. The nationalist vote was therefore split with the unionist candidate David Reid, winning the seat as a result.

Read more:

Cormac Moore: Was Eoin MacNeill to blame for Boundary Commission's 'disastrous' outcome?

United Ireland: How a border poll will be called - an explainer

An anti-partitionist electoral pact was also agreed between Sinn Féin and Devlinite nationalists for the 1921 election to the Northern Ireland parliament. It proved ineffective though, as both parties only won six seats each, with Ulster unionists winning 40 out of the 52 seats.

Nationalist candidates winning 33 per cent of the total vote and only 23 per cent of the seats is partly explained by the breakdown in the pact, with Sinn Féin leader Éamon de Valera complaining that the Devlinites made no effort to secure second preference votes for Sinn Féin.

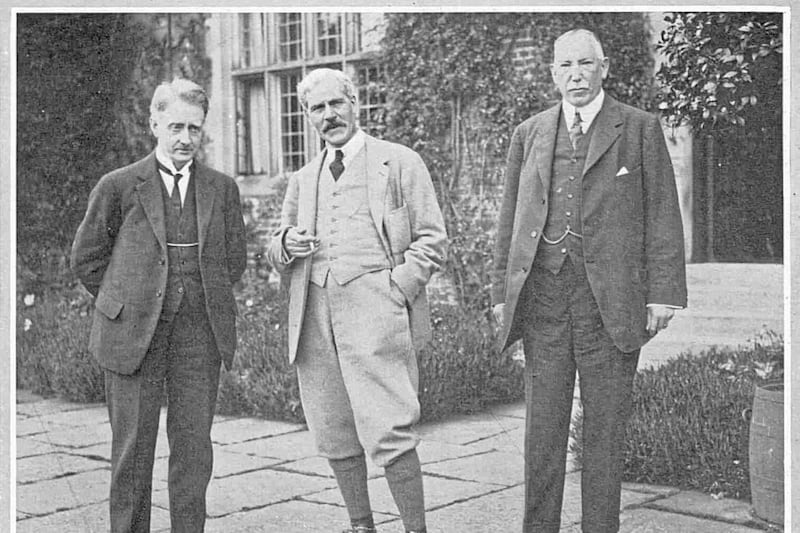

This may partly explain why, when Sinn Féin established a special Ulster committee in September 1921 to advise on Ulster during the Anglo-Irish Treaty negotiations, it rejected the help of resident northern nationalist advisers, such as Joseph Devlin.

Devlin, who had experience of negotiating with David Lloyd George, could have warned Sinn Féin to be wary of the British prime minister’s promises and commitments, which in turn could have prevented the vague and ambiguous wording of Article 12 of the treaty that resulted in such disappointment for nationalists by the Boundary Commission’s recommendations in late 1925.

Nationalist divisions

Division and lack of consensus also did not help nationalism’s attempts to successfully oppose Northern Ireland institutions. Even though many felt it was a temporary arrangement, the longer Northern Ireland existed and the more powers it received forced nationalists to choose between a policy of continuing to ignore its existence or using its institutions for the betterment of nationalists within Northern Ireland.

Recognising its institutions could be seen as legitimising Northern Ireland in many people’s eyes while ignoring the jurisdiction’s existence would mean no input whatsoever in shaping the policies adopted by the polity, regardless of its apparent temporary nature.

The lack of unity within nationalism on the issue of partition coupled with no strategic plans to overcome it or even deal with it effectively contributed to the terrible outcomes realised, particularly for northern nationalists.

Ambiguous on ruling coercion in or out, Michael Collins’s Provisional Government embarked on a non-recognition and obstructionist policy towards the north. When this failed, the Free State government sought better relations with the northern government but then did little to make this happen.

When there was co-operation between both Irish governments, it was done secretly, the Free State government always fearful of being identified as “partitionist” by its political opponents. Free State governments were more concerned about political divisions in the south than the schism they were fostering between northern and southern nationalists by their policies, which helped to copper-fasten partition.

How would a united Ireland work?

Today, there is a clear path to Irish unity through the mechanisms established under the Good Friday Agreement. While there are roughly 40 per cent committed unionists and 40 per cent committed nationalists who are unlikely to change their minds, about 20 per cent of the population of Northern Ireland need to be convinced that their interests lie in a united Ireland and not the United Kingdom.

This will not be achieved if only one version of nationalism is allowed to exist. To convince undecideds that a united Ireland will embrace differing political viewpoints and traditions, political parties who support Irish unity need to embrace each other and their differences more so than they do now.

Sinn Féin, the largest party in the north and likely to be the largest party in the south after the next general election, as well as being the most vocal proponent of a united Ireland, has a pivotal role to play here.

While its strategies of attacking the Irish state as being a ‘failed state’ and a ‘basket case’ might help to get Sinn Féin some votes in the south, it will not convince one undecided person to choose a united Ireland over the UK. It will have the opposite effect.

Although Michelle O’Neill has committed to being a ‘First Minister for all’ and demonstrated this in how she reached out to unionists on the death of Queen Elizabeth and the coronation of King Charles, Sinn Féin does little to prevent the toxic divisiveness of some of its supporters and members on social media platforms, who will not countenance any views contrary to theirs.

Zombie and Celtic Symphony

The recent hysteria over the singing of Zombie as well as the lyrics ‘Up the Ra’ from the Wolfe Tones' Celtic Symphony shows there is little scope for nuance currently from all sides, including from the Tánaiste Micheál Martin, whose suggestion that Sinn Féin is ‘infecting a new generation of young people’ was most unhelpful. It is apparent there is a much hatred within Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil for Sinn Féin, while Sinn Féin makes little secret of its revulsion of both parties. This antagonism will only increase as the general election in the 26 counties moves closer.

Northern nationalists have rightly been wary of political parties and governments from the south, who have in the past demonstrated sole interest in their own affairs and not those of the north. Contrary to what some claim, Fianna Fáil and Fine Gael are committed to a united Ireland though and will play an important role in convincing people to join a New Ireland, as will the SDLP.

Although some republicans believe that the Micheál Martin-led initiative, a Shared Ireland, is a sell-out, it is anything but. While it may not be as vocal as Ireland’s Future in calling and planning for a united Ireland, it offers practical, financial and educational support to foster better relations on the island, which surely must be seen as a good thing in a border poll context. It is perfectly ok to support Ireland’s Future and Shared Ireland.

To reach out to people who are not nationalists and who will decide the outcome of any border poll, it is necessary to embrace the different perspectives within nationalism and allow divergent voices to be heard and not shouted down.

If not, we are in danger of making the mistakes of the past by allowing intra-nationalist rivalry to scupper a clear opportunity to end partition and bring about a united Ireland.