ONE hundred years ago, on October 15 1919, a British government committee under the chairmanship of Walter Long met for the first time to draft the fourth home rule bill, which became known as the Government of Ireland Act 1920 in its final form.

This act led to the partition of Ireland. The committee’s first decision was to create distinct legislatures for Ulster and the southern Irish provinces. This was the first time that a separate parliament was proposed for Ulster.

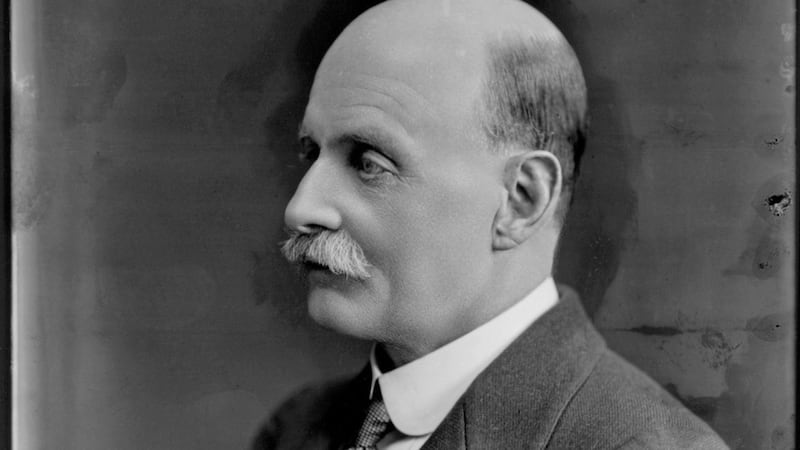

Walter Long was a staunch unionist and rabidly anti-Sinn Féin. Unsurprisingly, the make-up of Long’s committee was unionist in outlook. There was no nationalist representation whatsoever nor were nationalists even consulted. Ulster unionists were the only Irishmen consulted during the drafting of the bill.

Before the end of the First World War, the exclusion of Ulster, or at least some of Ulster, was the only option being considered in terms of special treatment for the province. On June 16 1919, Long was approached by John Atkinson, a unionist politician, lawyer and judge from Drogheda, Co Louth, who argued that neither the 1914 Home Rule Act nor home rule all round would work. He favoured a scheme that would place Ulster on a par with other provinces within a federal system.

On July 24 The Times of London publicly advocated the two-parliament option for Ireland for the first time. It proposed two provincial or state legislatures, one for the three southern provinces and one for Ulster, with the ultimate aim of an "establishment of an All-Ireland Parliament".

Days later, Long claimed that The Times’s "carefully thought-out scheme" was worthy of close examination.

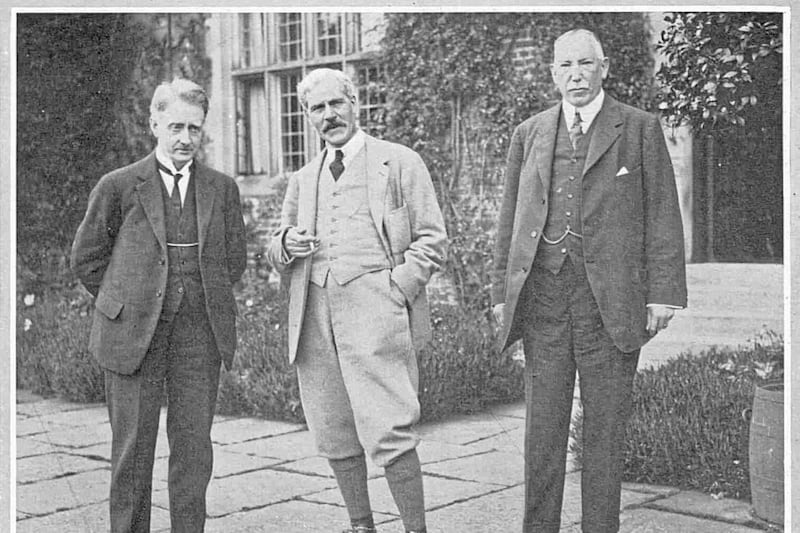

Throughout the summer of 1919, Long made a number of visits to Ireland to consult on the Irish question with the lord lieutenant, Lord John French, and the chief secretary, Ian MacPherson. Based on those meetings, Long sent a memorandum to David Lloyd George, the British prime minister, on September 24 recommending two parliaments for Ireland. This memorandum formed the basis of the subsequent Government of Ireland Bill.

The Government of Ireland Bill proposed that a Council of Ireland would be composed of 20 members from each Parliament. In the first year it would look after transport, health, agriculture and similar matters, afterwards working towards unity of the country. It was envisaged that the council would lead to the peaceful evolution of a single parliament for all Ireland.

Long knew the proposals would not placate Sinn Féin. It was never the intention to do so. The British government was only interested in securing the support of Ulster unionists. The Government of Ireland Bill did not try to solve the Irish question, it was an attempt to settle the Ulster question.

This was one of many objections from Ulster unionists. The main problems they had were; an admission of home rule, something they had never sought before; reduction of Ulster representation in Westminster to just 12 seats; and the abandonment of many Protestants and unionists to the southern jurisdiction.

Ulster unionists sought the six counties of Antrim, Armagh, Derry, Down, Fermanagh and Tyrone, and not the nine counties of Ulster, as this was the maximum area they felt they could dominate without being ‘outbred’ by Catholics.

To avoid a nine-county parliament, Craig had even suggested the establishment of a boundary commission to examine the distribution of population along the borders of the whole of the six counties. He would be vehemently opposed to the imposition of a boundary commission after the Anglo-Irish Treaty was signed in December 1921.

The decision of the Ulster Unionist Council was deeply unpopular among the 70,000 Protestants of counties Donegal, Cavan and Monaghan who were sacrificed to the southern administration. Thomas Moles, Westminster MP, explained that the three counties had to be abandoned in order to save the six counties: "In a sinking ship, with life-boats sufficient for only two-thirds of the ship’s company, were all to condemn themselves to death because all could not be saved?"

Ulster unionists outside of the six counties resigned from the Ulster Unionist Council. Many members of the Ulster Women’s Unionist Council from Cavan, Donegal and Monaghan also resigned. Outside of Ulster, southern unionists left the Irish Unionist Alliance and formed the Unionist Anti-Partition League, in opposition to the impending partition of Ireland.

Even though the Ulster Unionist Council endorsed the Government of Ireland Bill reluctantly, many Ulster unionists eventually concluded that the scheme proposed in the Government of Ireland Act "would cause the least diminution of their Britishness".

It has often been cited that the Government of Ireland Bill was allowed to pass relatively unchallenged due to the vacuum in nationalist representation at Westminster. There were just seven Irish nationalist MPs remaining in Westminster (six Irish Parliamentary Party members from Ireland and TP O’Connor from Liverpool) after the 1918 general election, instead of 80. It could be argued that even 80 nationalist MPs would have made little difference considering the make-up of the House of Commons after the election.

The Conservatives Party, Lloyd George’s Coalition Liberal Party and Irish unionists won over 500 seats, an overwhelming majority. It is doubtful that Sinn Féin’s presence would have made a difference.

Sinn Féin, of course, was not in the House of Commons to debate the Government of Ireland Bill. As the bill was making its way through parliament, the British government was waging a war with Sinn Féin and its military wing, the Irish Volunteers (renamed the Irish Republican Army). It was in an atmosphere of war, sectarian hatred and boycotts that the bill became an act on December 23 1920.

Despite the substantial opposition to the Government of Ireland Act, the British government continued with its implementation, with the act coming into effect on May 3 1921. Three weeks later, elections were held.

Known as the ‘Partition Election’, it determined the make-up of the first parliament of the new entity that was Northern Ireland.

:: Cormac Moore is the author of Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland, just published by Merrion Press.