EVEN at 80, Gerry Storey remains a man in demand. Try his mobile phone and, if you’re lucky enough to get him, the conversation generally goes one of two ways.

“I’m just on my way down to Dublin here, can you give me a shout later?” or “I’m just at the club here, can you give me a shout later?” He isn’t making up excuses, and when you do eventually catch up, he is all apologies for his unavailability.

Storey still trains the Irish women’s squad at the National Stadium every Saturday and is at his famous Holy Family Golden Gloves gym, just off North Queen Street in north Belfast, almost every day in life.

An original arrangement to meet at 1pm is moved forward an hour to allow the veteran coach to attend a photoshoot at Belfast Metropolitan College. Four days a week, Storey takes training sessions at City Centre Gym as part of Ireland’s first ‘boxing academy’, which was launched at Belfast Met last September.

At 12pm last Thursday lunchtime, Holy Family is empty apart from a gentleman patiently waiting for Storey in the hope that he can help him find a new home for some fitness equipment.

History leaps from the four walls of the gym. Muhammad Ali. Joe Frazier, a personal friend later in life. Hundreds of four-by-six prints of club nights at home and across the world intermingle with images of legends of the fight game.

As you stand at the entrance, high on the right is ‘paradise row’ - a line of shamrocks the length of the wall that bear the name and picture of some of the club’s most famous sons who have worn the green vest of Ireland.

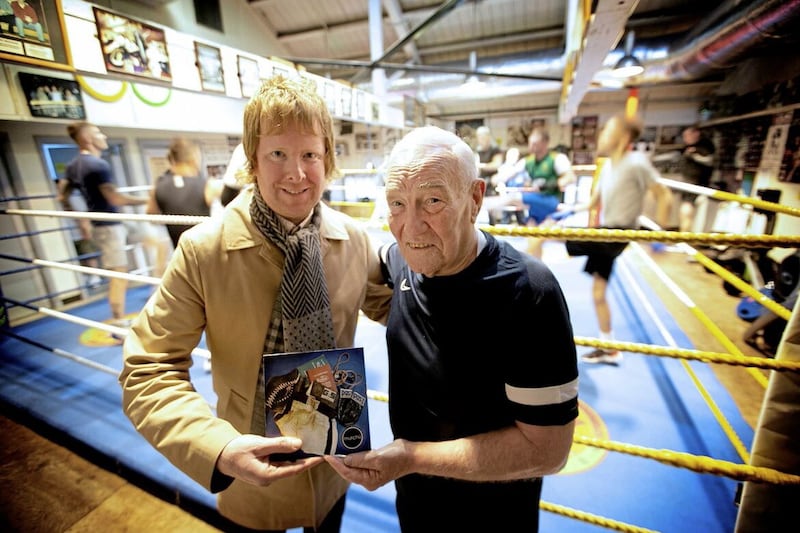

“There’s been some rows over these,” laughs Hugh Russell, the Irish News photographer and 1980 Olympic bronze medallist whose name and face take pride of place on ‘paradise row’ and elsewhere.

On the opposing wall hang the Olympic rings, which contain the names of all the fighters from the club who have headed far and wide to compete in ‘the greatest show on earth’. There are five, and counting.

When Storey arrives a few minutes later, rushing from a prior engagement, it isn’t long before the repartee between master and former student kicks off: “He told me lies for two years,” says Storey, pointing at Russell.

“He was going on for 11 for two years and, every time it came up to the championships and we needed his birth certificate, he took the flu and you didn’t see him for a few days.”

Russell, brought up at nearby Duncairn Parade, first walked through the doors of Holy Family when the club was based at Patrickville at the bottom of the New Lodge. He was nine-years-old - you had to be 11 before you were allowed to lace up gloves.

“Once the championships were over, the wee head came round the door and he was in again for another year. If he’d entered, I’d have found out his right age and I wouldn’t have let him in.

“The first time we took him to Dublin, he was only three stone seven or something like that - he could never make four stone. We put him on the swinging stool in the stadium and I had to lock my knee in it to stop him from swinging on out,” he said, before Russell piped up: “You wouldn’t have to put your knee on it now.”

‘JERSEY’ Joe Walcott versus Joe Louis. Early 1948, weeks after the pair had met at New York’s Madison Square Garden, the Alhambra theatre in High Street were showing the film of the fight.

The 12-year-old Gerry Storey went along to see Louis - ‘The Brown Bomber’ - in action, but left awe-struck by the skills of the man in the opposite corner: “I couldn’t get over this old guy going into the ring with the white shorts with a red diamond, shuffling, throwing feints to his left, then coming back to the right with a left hook.

“When the fight was over Louis was announced as the winner but he was already in the dressing room, he thought he was beat. And he was beat. From then on, I idolised Jersey Joe, still do.”

He didn’t know it then, but his calling to boxing was about to be answered. His father left when Storey - the youngest of four siblings - was just two-years-old. As he grew older, Storey was getting into scraps in the street and was up to no good before Jim McStravick, a professional boxer from the New Lodge, took the young man under his wing just months after his trip to the Alhambra.

“Jimmy took me by the ear one night and gave me a bit of a lecture," he remembers.

“My mother brought the four of us up on her own, my two sisters and my brother. So I reckon Jim was watching out for me because of that and he brought me up to the club. That was my introduction to boxing.”

A lazy eye put paid to his own career between the ropes at just 18 - “it was like looking through a car window that’s steamed up” - and fears that he could be left blinded if he carried on saw him turn his attention to coaching.

“When I boxed, my mother would have been doing a lot of worrying. I didn’t really realise how serious it was but, when we knew enough about it, we just said I couldn’t take a chance. By that time, I had been doing a bit of work with the younger ones and Jim took me aside one day and said ‘you're gifted at working with the kids’.

“The club was based at Chichester Park then, the Holy Family youth club and we moved down to Patrickville. There was an extension built for a card room and they give me it for two-and-six a week. That was us every night in the week then.”

That was just the beginning and, long before the High Performance unit, Storey was Ireland’s first national coach, taking teams to the Olympic Games in Munich (1972), Montreal (1976) and Moscow (1980).

Despite working at Belfast’s docks, boxing was now Gerry Storey’s life. His beloved late wife Belle used to joke about the transformation from part-time to full-time commitment.

“She was very understanding,” he said.

“She used to say ‘when I first got married and people ask me where Gerry is, I would look at my watch - now I look at the calendar’.”

But Storey’s bread and butter was at home in Belfast and at the height of the Troubles, while many clubs folded and interest in sport subsided, Holy Family thrived. Catholic, Protestant, it didn’t matter. Once inside, there was to be no mention of religion, no football shirts and, controversially for a boxing gym, no swearing.

“Big Stan Corbett, before he came in, he’d stand outside the door ‘f-f-f-f-f-f’, and that would do him until he got out.

“I never really would have said anything, but a lot of them would have just avoided it out of respect if I was there.”

Despite all that was going on in Belfast during the 1970s, Storey helped keep the international scene alive by bringing teams into Ireland. After being invited to a meeting of the UVF army council, he agreed to help organise shows at the Loyalist Club on Rumford Street, off the Shankill Road, with parallel events in the nationalist Ardoyne area often taking place in the same week.

Future stars like Russell and Gerry Hamill were often involved, as was Barry McGuigan. Storey remembers McGuigan’s father Pat would drive to Belfast from Clones every Friday to leave his son with the Storeys, before collecting him on Sunday night. It was a tough grounding but, no matter where they went, the Irish team was roared on by a partisan crowd.

“It was hard to get teams to come in then because they were afraid to come into the north, especially Belfast.

“A lot of them just had to trust me and they did. You would have a show in Rumford Street on a Tuesday night, Crumlin Star on a Thursday. It was a big thing for Ireland to box on the Shankill, but we had teams from Poland, Germany, Scotland, Italy all come over... Before you knew it, we were established.

“Supporters were coming in from both sides. At one show I saw big men crying with each other because they hadn’t seen each other since the start of the Troubles.”

His cross-community involvement didn’t end there as, during the 1981 Hunger Strikes - with tensions at their height - Storey received another unexpected request, this time from the Maze prison.

“The Sports Council and other ones from the government told me the paramilitaries on both sides wanted me into the cages to train them,” he recalls.

“They told me all the prisoners in the Maze, on both sides, were refusing to take part in physical education and that none of them were speaking to anybody. I went out to talk to them, the governor was with me, and met the OCs of each compound. It was strange, but I agreed to do it.

“You’d have been in with the UVF, or whoever, and they’d have said ‘how’re the boys getting on?’ The boys meant the Ra. I told them I was having problems getting basic boxing gear for them, so they said ‘take our stuff Gerry’ - as long as you have it back on Thursday.

“That’s how it was in there. They were killing each other outside, but inside it was different, they seemed to help each other.”

“MAKE sure you tell him the one about the ambulance…”

Hugh Russell has finished photographing his former mentor and is getting ready to move on to the next job, but not without a bit of gentle prompting. Storey smiles as Russell takes up the tale.

“Gerry’s car broke down on the motorway and he flagged down an ambulance. An ambulance! So we actually went to the fights in an ambulance. I’ve heard of boxers leaving a fight in an ambulance, I’ve done that, but going to a fight in an ambulance?”

On his way out the door, Russell turns on his heels once more: “Remember the time the police stopped you when we were all in the car? Tell him that one,” he adds before saying his farewells and heading down the stairs.

“I was stopped at Carrick town hall and the cops opened the door, they knew me anyway, it might even have been an RUC bill… How many were in the car?”

“Y’know… hold on... HUGGGGGGHHHH…”

Storey’s voice echoes around the gym and is followed by the gentle sound of footsteps coming back up the stairs: “Thirteen,” says Russell.

“Patsy Reid, the big heavyweight, they were all in it - from me up. We were all on top of each other in Gerry’s wee Polski Fiat, I think it was…”

Storey continues: “The cop opened the door and said ‘good Jesus Gerry, how many are in there?’ There was a full team and they all just came out one after another, boom, boom, boom…”

More than titles, more than money, more than gold, silver or bronze, it is the personal relationships Gerry Storey has built with his fighters - now friends - down the years that matter above all else.

Then, as now, he transcends generations. The likes of Paddy Barnes, Ryan Burnett, Carl Frampton and Michaela Walsh have passed through his hands in the past decade alone.

Barnes’ father, Paddy senior, used to tell his son to “go down and see your real da” when the three-time Olympian would sacrifice family arrangements for a session with Storey.

On the day of his 80th birthday - April 7 - he was greeted at the club by the sight of Barnes jnr hurriedly tying balloons to the railings. The pair formed a special bond after Storey helped turn Barnes from a novice who had lost his first 12 fights into a man tipped to win gold in Rio this summer.

“Paddy’s a winner, always has been," Storey says.

“Even when he was losing, he would have gone in with King Kong, he didn’t care. He just wanted to get in and win. I got a great kick when he won his first national title. Without saying it, or showing it, inside you get a great kick from it.

“The same way I always remember Hugh [Russell] and [Gerry] Hamill coming back from Dublin. They were down at the station and Hamill came out with Hugh on his shoulders. They were both national champions. That has never left me.”

The buzz he gets from seeing progress, no matter how slow, is undiminished: “I always refer to John McStravick and the others what they did for me - God knows where I’d have ended up if they hadn’t got me into the club. That has stayed with me all my life.

“Then when I realised what my mother went through bringing us up - you don’t think of it then, but as you get older you do. You wonder how many kids there were like me who were running about and maybe Jim and other ones brought them into the club.

“I get a great kick out of bringing them up from level A, B, C, D right up to international status. Any kid who comes in I’ll say, there’s your target. You start at the Antrim championships, then the nationals, then you’ll box for Ireland. Paradise row they call that,” he says, pointing up to the right.

“After that, you go to the Commonwealths, then the final stop is the Olympics. That’s your dream.”

Gerry Storey’s appearance at the Belfast Met photoshoot didn’t happen, lost in the mire of mulled over memories almost three hours later. A surprise visit from another club old boy, former featherweight champion Sammy Vernon, opens up another conversation and a whole new set of stories.

As the interview draws to close, attention turns to what the next 10 years might hold: “Something the same - I tell them I’m only starting in this game,” laughs Storey.

“God’s been good to me because I’m still able to run around like a wee lad. Maybe it does keep me going, I don’t know. When you talk about all the things that have happened, what do you do? It’s like a grain of salt, it happened and I just keep doing what I’m doing.”

The day Gerry Storey stops doing what he is doing will be a sad one for all who have been a part of Belfast and Ireland’s boxing story. But there are no plans to stand still just yet. Not while there are yarns to be told, champions to be nurtured and dreams yet to be fulfilled.

After all, life begins at 80.