“I have a new dream. It is to return to Northern Ireland in a few years with my young son. We will roam the country, taking in the sights and sounds of that lovely land. Then, on a rainy afternoon, we will drive to Stormont and sit quietly in the visitors’ gallery in the Northern Assembly. There we will watch and listen as the members debate the ordinary issues of life in a democratic society: education, health care, tourism and agriculture.

"There will be no talk of war, for the war will have long been over. There will be no talk of peace, for peace will be taken for granted. On that day, the day on which peace is taken for granted in Northern Ireland, I will be fulfilled and people of good will everywhere will rejoice.”

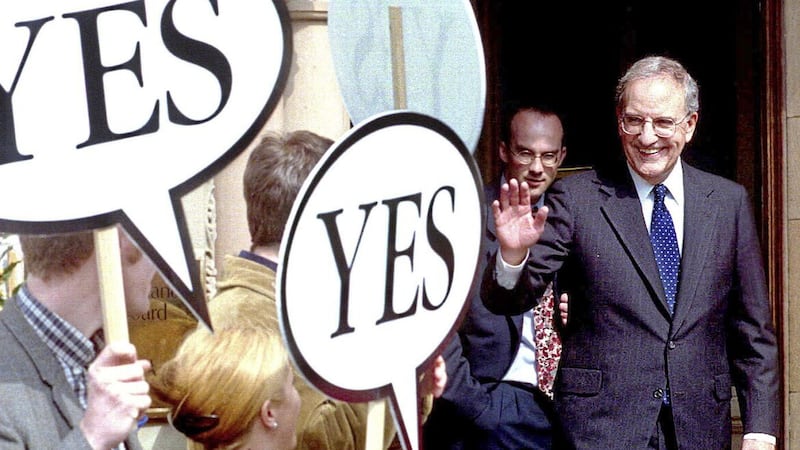

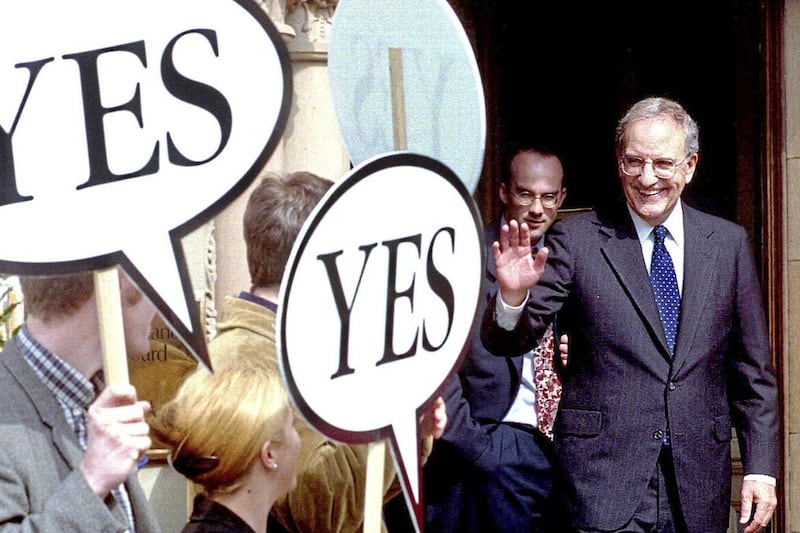

That was George Mitchell, speaking six months after he had brokered the Good Friday Agreement. I can’t remember if he and his son Andrew, now 26, ever made that trip and sat in the gallery listening to members debating the ordinary issues. I hope they did, because at almost 90 it’s unlikely that he will now be able to do so. Maybe Andrew can complete the dream for him at some point, although it can’t be taken as a given that the assembly will even meet again, let alone debate ordinary or extraordinary issues.

There was a time when I shared George’s dream. I hoped that I would be able to sit in the visitors’ gallery with my own children (who says I don’t believe in spoiling them) and allow them to watch civil debate combined with consensual governance.

Indeed, one of the reasons I voted Yes in 1998 was my hope that the next generation would have political choices and expectations that weren’t available to me between 1973 (my first vote) and 1998. I hoped the shadows of the gunmen and serial gurners would be blotted out by the sunshine of new ways of doing political business in Northern Ireland. And I hoped my children would be able to take part in serious, honest political discussions without having to worry which foot their friends kicked with.

We are not there yet. Nowhere near it, in fact.

In fairness, I knew it would be a long haul before we removed enough baggage from the past to clear a walkable path for our children to lay the foundations for the way forward.

I knew we would continue to scratch old scabs and sores; continue to doubt the sincerity of old opponents; continue to believe that ‘themmuns’ had got the better part of the deal; and continue to judge every piece of legislation against the yardstick of who had compromised more.

We are certainly better off in terms of personal safety. We don’t gather around the radio and TVs to hear the last bulletins of local news and worry about members of the family who haven’t returned home at the expected time.

We don’t collectively leap at the sound of a backfiring car or worry too much about a couple of guys standing at a corner. We don’t automatically assume that an unexpected thud is a bomb. We don’t have to walk behind the coffins of those slain by one paramilitary group or another. And yes, for all of that we should be grateful.

And yet... On Tuesday afternoon the threat level in Northern Ireland was raised from ‘substantial’ to ‘severe’, meaning that attacks are now highly likely. Not much of a 25th anniversary present, is it?

The assembly remains in suspended animation, as it has for most of the five years since the 20th anniversary. There’s a lot of hoopla about the GFA right now, but very little about how, exactly, we make it through the next 25 years.

We don’t hear the debates in the assembly, but we can see the daily consequences of the failure to resolve problems in health, education, infrastructure and just about every other area of governance. The thrill of 1998’s hope has morphed into a catchpenny cliché to be trotted out by politicians in a variation of “At least the bad old days have gone”. Have they? Isn’t that their shadow I can see creeping across the landscape?

In an essay for a special issue of the Fordham International Law Journal in April 1999 (celebrating the GFA), Billy Robinson and Stevie Nolan wrote: "Our prejudice, mistrust and unwillingness to talk have prevented us from resolving our conflict, and unless we do, it will return. Violence is not new to this island and there is no certainty that it will not return. In 1921, when the last peace treaty was signed, it was signed by two warring governments, no one voted for it, and even fewer agreed. This time we have voted, we do have agreement, and we have the best chance in our histories to break that cycle of violence. If the opportunity presented by those who have taken risks to bring about this agreement is not to be wasted, then we must all take responsibility to ensure its success."

They were right. And they remain right. The 1998 peace/political process is closer to collapse than most people realise, partly because too many continue to delude themselves with the belief that it is too big to fail. It isn’t. It is failing every day: and every day of failure drags it further away from its intended purpose.

And here’s the real kicker: its failure will signal that we cannot find a way to make Northern Ireland work, which will, in turn, raise a new host of questions about what to do next. Nothing persuades me that we are ready to face that brutal reality.