MY favourite headline from last week was wonderfully surreal: 'Colombian President Juan Manuel wins Nobel peace prize, despite peace deal being voted down in a referendum.'

So why did he win it? Why didn't the judges just decide to withhold the prize this year? Better still, why isn't the Nobel peace prize awarded only after it is clear that the peace agreement is actually working and has made a difference to the politics and society of the country concerned? To paraphrase Yeats: "Peace comes dropping slow, but peace prizes nowadays are as thick on the ground as the dashed hopes and broken promises of the agreements for which the prizes were awarded."

In 1976 the Nobel Peace prize was awarded to Betty Williams and Mairead Corrigan for founding the 'Northern Ireland Peace Movement.' Their efforts, though well intentioned, didn't make a button of difference here. The Troubles continued for another 20 years, their movement didn't produce new political parties, they weren't responsible for anything of lasting political significance and the movement itself became embroiled in internal squabbles before disappearing.

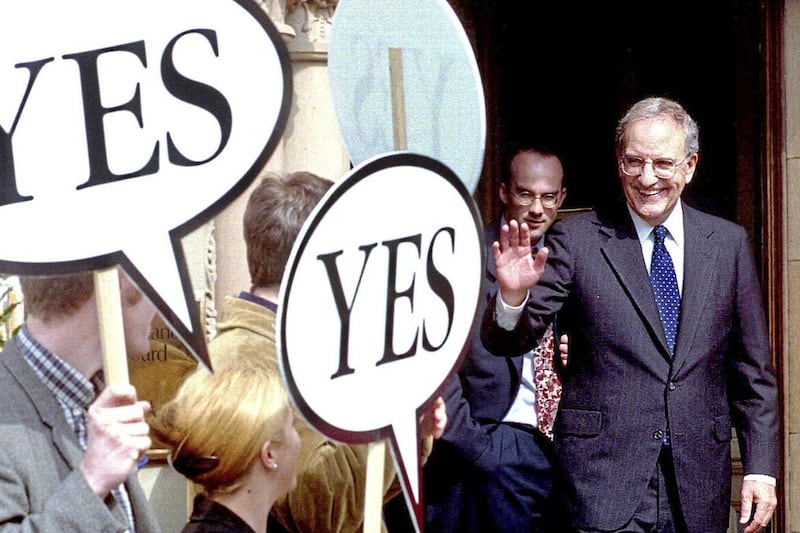

In 1998 David Trimble and John Hume were the joint winners for, 'their efforts to find a peaceful solution to the conflict in Northern Ireland.' Yet both the UUP and SDLP were later shafted by the British/Irish/American governments and looked on helplessly as the DUP and SF concluded an entirely different agreement which resulted in a sectarian headcount at the heart of government and a blind eye being turned to just about every difficult decision they were asked to make.

In 2009 Barack Obama - barely settled into the White House as President - won for his 'extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and cooperation between peoples.' Hmm, I wonder what the judges would think of his efforts now that he's reaching the end of his term of office; particularly the legacy of his key diplomats, John Kerry and Hillary Clinton? A lot of fine words, an awful lot of pieces of paper, never-ending meetings, and yet precious little to show in terms of anything being settled, let alone nailed into place.

In 2012 the European Union won for, 'over six decades contributed to the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy and human rights in Europe.' Ironically, the prize was awarded at the same time as the EU was coming under huge internal political and financial crisis and when a new form of virulent nationalism was raising its head across a dozen or so member states. No mention, of course, of the fact that eight of the EU states were in the top 20 of the world's largest arms exporters: keeping their own backyards clean while selling death across the world. And let's not forget the numerous awards to Middle East leaders - Israeli and Palestinian particularly - for agreements and peace deals that toppled back into war before the ink was dry.

Peace prizes, especially the Nobel one, have become like Oscar ceremonies. It's usually the flashy, studio-hyped, massively-marketed films that make the most noise and win the Oscars; yet within a few years they're mostly forgotten and don't stand the test of time. Peace prizes are now handed out to make governments and party leaders feel good about themselves. They're also handed out as part of an orchestrated publicity hoopla to boost the confidence of voters and old enemies who might just be in the mood to fall for the Pollyanna spiel peddled by government-funded PR companies - some of which have been set up for that very purpose.

When it was announced that Trimble and Hume had been nominated for the Nobel peace prize I wrote that they should turn down the prize or, at the very least, ask for the award to be held over until, "it has become clear that the people of Northern Ireland have bought into the deal, that all of the parties and paramilitaries are honouring their side of the bargain and that a new political/societal era has kicked off." Peace prizes should never be given in hope: they should be given as a reward for measurable delivery and palpable change.

I supported the Good Friday Agreement because I believed that it offered an opportunity that wouldn't come along for, perhaps, another generation. But that's all it was; an opportunity. I acknowledged - and wrote about it at the time - that the agreement mightn't work. I knew that 'constructive ambiguity' could very quickly turn into destructive clarity. I accepted there were huge risks, but I believed that the risks were worth taking. But at that point none of this, the agreement, the hope, the negotiation process, or the lead negotiators, justified the award of a peace prize. It was nothing more than a PR, political marketing prize: as are most of these peace prizes.

Peace should be its own reward. Citizens should be the collective beneficiaries. Parties should build the post-conflict societies. I think it's about time we stopped handing out prizes to the chosen few. If they've done well, history will be kind to them. And that should be good enough.