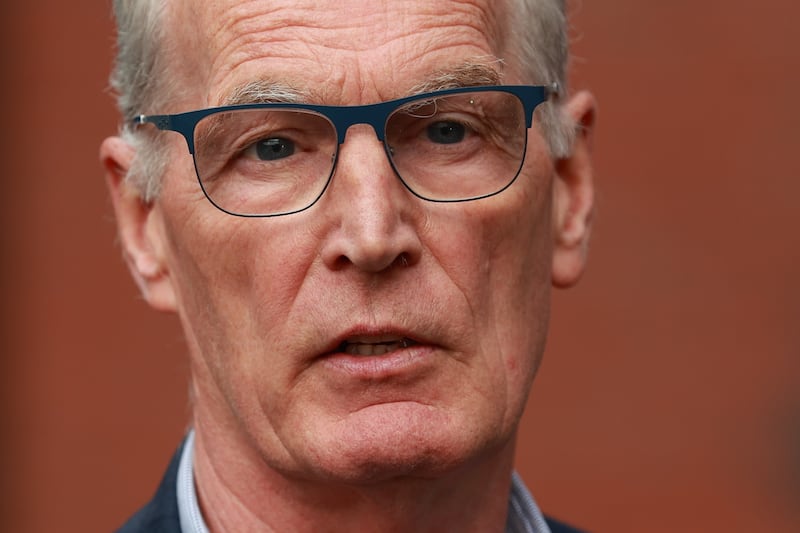

“It’s time to begin planning for the delivery of all public services on a fully integrated, all-Ireland basis,” Declan Kearney posted on X last Friday.

The Sinn Féin national chairperson has written about this before. Integrating public services would appear to make perfect sense for republicans, as a strategic objective and a conveyor belt of interim achievements en route to a united Ireland. If Sinn Fein gets into power on both sides of the border it will have to do more than set up a citizen’s assembly and pester London for a border poll. These are stalling tactics, as would be clear after several years in office. However, Kearney is setting his party an extraordinary challenge. Even apparently straightforward cross-border cooperation tends to prove enormously difficult.

Assuming devolution returns, the Good Friday Agreement provides almost limitless scope for all-Ireland integration - in theory. Stormont and the Irish government can work together through the North-South Ministerial Council to cooperate on anything within their remits “where there is a mutual cross-border and all-island benefit”.

They can do this through existing structures or by setting up a new cross-border body. Sinn Féin could propose creating ‘Educate Ireland’, for example, to harmonise exam systems and professional qualifications so pupils and teachers could transfer more easily between jurisdictions.

The fact is that more people are engaged with the idea of Irish unity..

— Declan Kearney (@DeclanKearneySF) December 29, 2023

The discussion is now centre stage.

It’s time to begin planning for the delivery of all public services on a fully integrated, all Ireland basis. pic.twitter.com/CseKxsdsNJ

In practice, unionists would veto this proposal and anything like it. A new cross-border body would require cross-community support in the assembly. Sinn Féin could attempt harmonisation without a new body by taking the education portfolios north and south and getting its ministers to work together. It lauded this exact possibility when it took the Department of Education after the St Andrews Agreement.

However, St Andrews introduced a petition of concern-type mechanism to the executive, allowing any three ministers to require a cross-community vote on anything significant, controversial or cross-cutting.

Unionist vetoes and Sinn Féin’s department picks

The DUP will have three ministers in a restored Stormont, including its deputy first minister, or four if the UUP goes into opposition.

Would unionists always veto cooperation? In 2013, DUP health minister Edwin Poots worked with his southern counterpart to establish all-Ireland children’s heart surgery in Dublin. Although Poots faced some tasteless gloating, he said the decision was too important to fret about any implied constitutional subtext.

It is unlikely the DUP would have such confidence as the second largest party, with Sinn Féin presenting every act of cooperation as advancing a united Ireland. Nor would most proposals be matters of life and death.

The departments Sinn Féin picks in any restored executive will be revealing. It is entitled to three, or four if the UUP and Alliance go into opposition, plus it will have first choice under the d’Hondt process. So it cannot pretend it wanted key departments and missed out on them - avoiding difficult jobs will be obvious.

Serious harmonisation requires choosing health and education, representing half and a fifth of the budget respectively. Housing is Sinn Féin’s stated priority in the Republic, so it might also need Stormont’s associated Department for Communities.

If Sinn Féin picked the right departments and the right policies to get past unionist vetoes, it would then hit the real brick walls of policy delivery: bureaucratic inertia and vested interests.

The departments Sinn Féin picks in any restored executive will be revealing... Serious harmonisation requires choosing health and education, representing half and a fifth of the budget respectively. Housing is Sinn Féin’s stated priority in the Republic, so it might also need Stormont’s associated Department for Communities

Little needs to be said about the challenge of delivering radical change in the public sector, let alone in two public sectors divided for a century. But it is especially telling that the trade union movement has always been organised on an all-Ireland basis, yet has never shown much interest in reducing cross-border barriers to employment.

Cooperation could also generate resentment from taxpayers and service users if it is seen as unfairly impacting costs and queues - this will be a risk wherever services are under pressure. Perversely, cross-border usage of services will probably always be low, confined by definition to border areas. During the pandemic it emerged only 550 children were crossing the border for school each day, in both directions. How many votes are there in making such services easier to use?

Unionists might hope Sinn Féin will disappear down a rabbit hole in pursuit of this all-Ireland vision. Sinn Féin might hope unionists will veto everything it proposes, letting it keep the vision alive while avoiding the blame for lack of progress.

Precedence suggests any such republican cynicism would be warranted.