RUMOUR always only is what it is until proven otherwise. Innuendo operates off the same loose principle. How often does a whisper turn into a echo and later prove to be no more than a murmur?

Players and squads are so insulated now from the outside that nothing gets out. Or in. Or if it does, it’s diluted as quickly as possible. The public crave information and insight, which is why any snippet or loose off-the-record comment is taken as gospel disseminated to the masses.

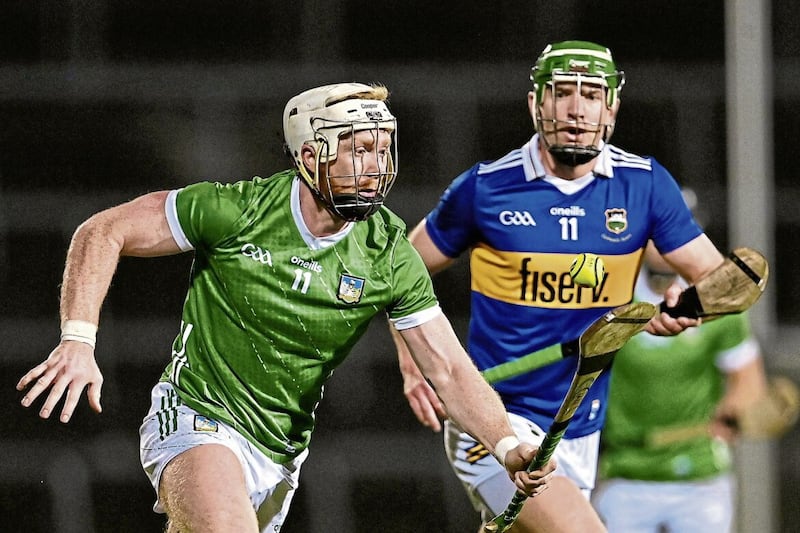

The word on the ground in Limerick over the last week is that Cian Lynch has been playing out of his skin – at centre-back.

Lynch has no history of playing in the position, but with Limerick without the services of Declan Hannon, their captain and leader, slipping a two-time hurler-of-the-year in as his replacement, with Lynch having missed the Munster final through injury, seems like the perfect response.

Lynch is more known as a midfielder and forward – so why would Limerick need to go down that road anyway when they have so many fluid defensive options?

Kyle Hayes did well when taking over at number six after Hannon went off in the Munster final. Dan Morrissey can play there. So can Barry Nash.

Darragh O’Donovan has done a stint at centre-back in the past. Outside of Hannon, Diarmaid Byrnes is the best club centre-back in Limerick with Patrickswell.

Richie English and Colin Coughlan can also play there. Getting another established defender to slip in to Hannon’s role would still mean having to start either English or Coughlan, which is something John Kiely and his management seem reluctant to do.

Despite his inexperience in the role, it would still seem like a job Lynch would be more than capable of. As well as being as brave as a lion in the air and on the ground, his reading of the play, combined with his intelligence and playmaking genius, could give Limerick a whole different kind of creative platform from which to build.

Whether or not Limerick have been toying with the idea, it’s still not like them to pull a rabbit out of the hat, especially when it hasn’t been their style in the past.

Tipperary were thrown off track when Hayes turned up at wing-back in the 2020 Munster semi-final, while Cork were flummoxed when Hayes landed in at full-forward in their first round-robin game last year. But they don’t see those marginal gains of being any real consequence to them.

Everything they do is in plain sight. Every match Limerick play is analysed in microscopic detail, frame by frame, but there is no secret.

Limerick’s predictability in so much of their play is their greatest strength because they are so comfortable and so good at what they do.

Limerick are the exemplars of that governing principle that practice is a particular type

of repetition without repetition.

Much of that philosophy governs the thinking of Paul Kinnerk, the tactical mastermind and key strategist behind Limerick’s dominance. Limerick’s system of play has become heavily ingrained now from repetition without repetition because Kinnerk repeatedly challenges the players through representative learning design.

Kinnerk’s coaching detail has developed so many enablers within their team that Limerick thrive on pattern recognition within their system. Limerick understand the principles and patterns and they can perceive and action those moments faster because there is a logic or a curriculum to what they are doing. And they play with such synchronicity because they have recognised the patterns developing.

As with any successful team though, there can be a tendency to inflate the myth around them from the outside.

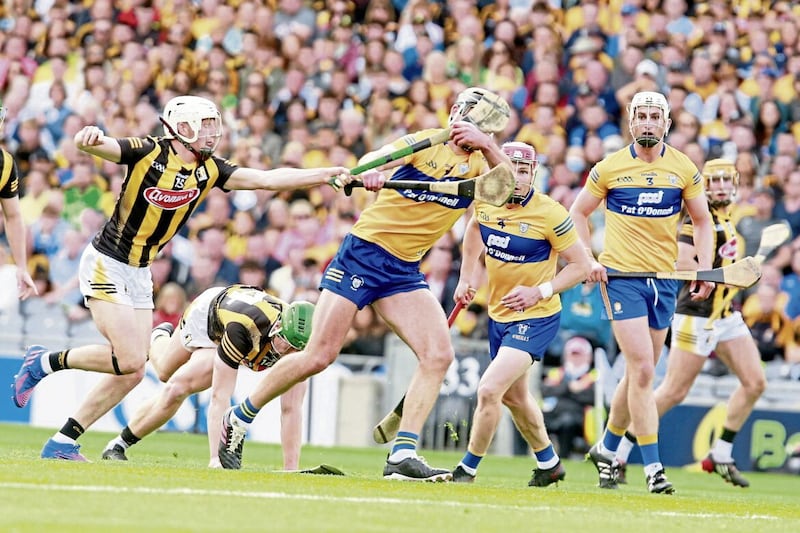

In so many ways, Limerick now are a carbon copy of Kilkenny at their peak under Brian Cody; they have the best players; they are physically superior to everyone else; their culture drives their ambition; their success pumps their confidence; their manager constantly demands more; the crucible of their training ground environment sets their standards.

Throughout Cody’s two-and-a-half decades as Kilkenny manager, their training sessions in Nowlan Park always had a particular meaning, standing for a value system which meant that there is no hiding place. Everything is revealed in plain sight, which means the ultimate test of the players’ endurance – mind and body.

Limerick’s crusade has been similar to Cody’s Kilkenny in their prime but the demands on the machine have been stress-tested to the limit this season.

Hannon is gone for Saturday’s All-Ireland semi-final against Galway. Seán Finn is out for the season with a torn ACL. Lynch has been injured again. Key players are still not performing at their usual levels. Limerick are not hitting their normal metrics. And yet, they are still winning.

Everything Limerick have built, everything they stand for, is controlled and deliberate, designed to protect against chaos and disruption.

Nobody has any right to doubt what they are capable of, but how much is too much?

Limerick’s turnover numbers in their own half have sky-rocketed because teams have gone after them higher up the pitch. Byrnes’s free-taking isn’t bumping up their numbers like it did last year. Limerick aren’t getting off as many shots.

They managed without Lynch last year. They won the Munster final without Lynch too, but Hannon’s loss now, combined with Finn’s, poses a whole new challenge – not because of the job Hannon does, but of how he does it as their leader.

The intensity and precision of Kinnerk’s sessions is like a firewall to prevent it from shutting down, or being shut down. But it’s still never that straight-forward.

When Kilkenny won the four-in-a-row in 2009, they looked untouchable at the outset of the Championship, but they needed an outstanding goalkeeping display from PJ Ryan in the final to win the All-Ireland.

Kilkenny only played four games that summer. Limerick have already played five.

When the wheels eventually came off for Kilkenny in 2010, injuries derailed them.

Limerick have overcome every challenge imaginable. But can they overcome a Galway side now who have been waiting 12 months – and longer – to take them down?

If Limerick do, they will lay another slab on their path to greatness.