THE butterflies start doing a loop the second Chris Lynch shuts his hotel door and sets off to meet the Australian national team and staff at Sydney’s Olympic Park.

Ahead of a friendly double-header with Ecuador last month, this camp is the first time the Socceroos have come together since departing Qatar in early December, their stoic performance against eventual champions Argentina gaining greater kudos the longer the World Cup wore on.

It is a first for Lynch too. Appointed Australia’s national wellbeing manager just weeks before the action got under way in the Middle East, the time between has been spent trying to establish where he fits in the system, and what he can bring.

“You’re sitting back and analysing things - what’s currently in place? What do the coaches see as beneficial – what is their view of wellbeing?

“It’s a very new concept, and wellbeing means different things to different people. I am part of embedding what the wellbeing identity is for Football Australia... essentially supporting the personal development and wellbeing of players and staff representing the national team.”

Having made the two hour trip across from Adelaide, the west Belfast man attends training for a couple of days before the first Ecuador friendly.

So much in life right now is new - new country, new house, new job. Just last week he and partner Marli welcomed new baby Finley James into the world.

Yet watching the players, the different drills, the subtle movements, the shouts, the sounds, the laughter, it all feels familiar. He could be back on Hannahstown hill, a gale blowing across Páirc Lámh Dhearg, or Casement, his and many others’ field of dreams, so reminiscent was it of the place where it all began and, ultimately, what brought him here.

Sport has always been at the epicentre of everything for Chris Lynch. Early years living in Ballycastle coincided with Antrim’s unforgettable run to the 1989 All-Ireland hurling final, an immersive experience even as innocent eyes followed from the fringes.

“That lit a fire in so many people.

“‘Sambo’ [Terence McNaughton], ‘Humpy’ [Paul McKillen]… the beautiful jersey with the pinstripes. Watching that team and what they did, I knew I wanted to play for Antrim.

“If you can’t see it, you can’t be it.”

That ambition was realised, though not necessarily how he imagined.

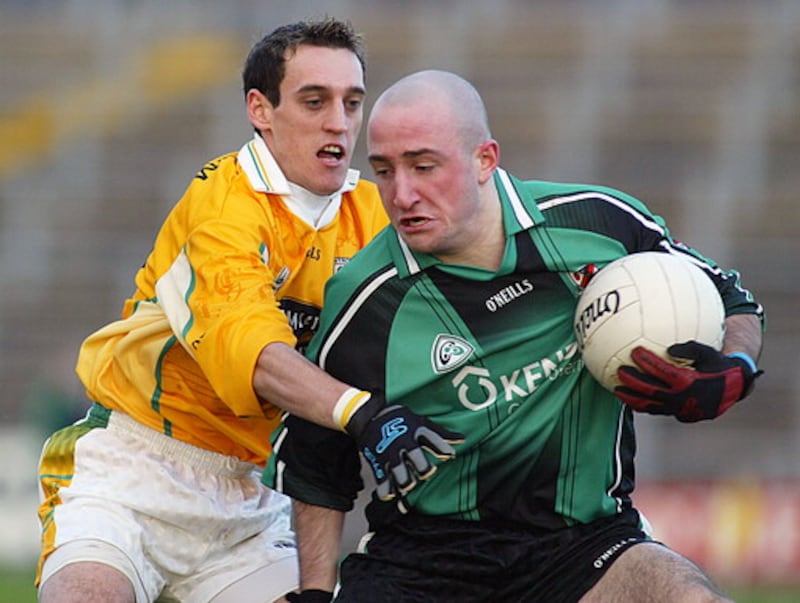

Lynch played county minor and U21 in both codes, became understudy to Saffron stalwart Sean McGreevy between the sticks before telling PJ O’Hare he wanted to try his hand out the field, where he played for Lámh Dhearg.

“I was wing-forward, half-back, corner-back.

“PJ’s son Adam would always be with the squad when PJ was there, and he used to say I’m the only man who ever played every position for Antrim. He was probably right.

“It was a blessing and a curse.”

When a shattering knee injury signalled the premature end of a stop-start inter-county career at 25, Lynch would have given anything for one more campaign. One more game even. Wing-forward, half-back, corner-back, goalkeeper even. It didn’t matter.

Instead, mourning the death of a dream became all consuming, to the point where darkness descended day and daily.

From that suffering, though, came strength, a different sporting path leading to a new life, and a new love, on the other side of the world.

********************

IT was 2008 when the first warning signs began to appear, not that he knew what they were.

By that stage Chris Lynch had been around the Antrim senior set-up for seven years, performances for the county U21s ensuring a swift segue into boss Brian White’s thoughts as the number one jersey, unwittingly, became his focus.

“I never wanted to be a goalkeeper,” he smiles, “I was just really good at it.

“My family almost disowned me for this, but at 14 I left Lámh Dhearg for St John’s… I had friends at school, one of my teachers was Raphael Gatt, I was put in nets one day and had a stormer. Next thing I’m being playing Beringer Cup for St John’s with ‘Locky’ McCurdy and guys like that, people I looked up to who had represented Antrim.

“I came in with Antrim under ‘Whitey’, and Sean [McGreevy] was brilliant with me. There was no rivalry - Sean loves Antrim, and he wanted me to be better because we were all in it together.

“It was a great group of players to be with, and coming up through minor and U21 you sort of believed you could do something. That’s one thing I learned from Anto Finnegan – Anto was a mentor when I first started going to summer schemes at Lámh Dhearg - big Joe Quinn, Frankie Wilson, being around Sean Kelly and the St Gall’s players, there was enough talent and leadership to do something special.

“Like, at U21 level we were beating Tyrone, we beat Armagh at Casement Park after going down to 14 men. There are systemic things in Antrim that just impacted - club rivalries being one of them – but you had people who wanted to take Antrim to the next level.

“And there were some incredible days. Being involved as sub goalkeeper when we beat Cavan [in the 2003 Ulster Championship], Darren O’Hare telling Tyrone we were coming for them… it was brilliant.

“Antrim was everything to me then.”

Tyrone, on the way to a maiden All-Ireland title later that summer, proved too strong for the Saffrons at a heaving Casement Park weeks later, building on those small breakthroughs something Antrim always seem to struggle with.

Lynch continued to learn from McGreevy but, surveying the club and county landscape – as well as considering his own playing ambitions – the time would come to stick or twist.

“I was playing outfield for Lámh Dhearg, there was good goalkeepers coming through like Chris Kerr at St Gall’s, John Finucane was there with Lámh Dhearg and Antrim and my own brother Damien was with the county minors… it made more sense to me to follow my ambition outfield.

“PJ told me I’d have to come to trials like everybody else - I went and he picked me. But I could never really lock down a position. Eventually when Jody came in I found a position at wing-back and went from there.”

Former Tyrone footballer Jody Gormley took up the Antrim reins in 2007 but, despite finally nailing down a starting spot, it wasn’t long before Lynch got itchy feet.

Now 23, and with friends jetting off to sunnier climes in search of adventure, there was a sudden appeal to upping sticks and sampling something different. When an offer arrived to head out to Boston and play for Aidan McAnespie’s in 2007, he was gone within a week.

It was only in later years, though, that the pieces of his story began to come together.

“I was basically just running away from my own mental health issues.

“I was playing really well, and any chance to pull on an Antrim jersey was a privilege for me because I sat on the bench more times than I played over the years.

“But there was something I just wasn’t dealing with in my head, I didn’t know what it was. I didn’t really sit down with Jody face-to-face, I just disappeared into the ether… I didn't handle it very well.

“There were a couple of deaths in the family, a break-up of a relationship… sport was my outlet, but there was just something that wouldn’t go away. You didn’t learn to deal with mental health issues growing up because people weren’t taught how to. You just… got on with things.

“At that time I just needed to get away.”

The knock-on was that he missed Antrim’s Tommy Murphy Cup triumph, with a double-whammy waiting around the corner.

After successfully trialling under new Antrim boss Liam ‘Baker’ Bradley upon his return, a delayed suspension arising from his transfer to McAnespie’s – “I wasn’t officially registered in America… somebody didn’t do the paperwork properly” – meant he wasn’t allowed to play any part in the county’s momentous run to the 2009 Ulster final.

Then, before the year was out, Lynch’s world was shaken to its core.

“When I came back from Boston I injured my knee playing for Lámh Dhearg.

“I got the operation, tried to come back, eventually did come back and play for Lámh Dhearg, then a surgeon tells you you’re not going to get back to that level, and that you couldn’t play for Antrim again.

“That was really hard, probably the lowest point in my life being honest, because you’re confronted with an identity crisis – it felt like it was the death of me.

“I’m working with young people now, talking about their place in the world, their passions, and something you realise over time is that what you do should never be who you are.

“I treated myself like a professional Gaelic footballer. I got jobs to work around football. No-one ever taught me – and even if they had I don’t think I’d have listened – how to deal with these things socially, emotionally, psychologically. It just wasn’t spoken about.

“So when something like that happens, it’s like a bomb going off.”

Lynch could feel his mood dip as each week passed, but coping with an existential crisis wasn’t something he was equipped for.

“It festered and festered. I didn’t want to tell people, didn’t know how to tell people.

“The GPA [Gaelic Players’ Association] was around then, but it was more about fighting for two jerseys a game, or stuff relating to money. It wasn’t really about what a union should be standing for, or what it is today.

“I became angry, I wasn’t a good person to be around. I isolated myself from the club, people didn’t really understand why I’d just taken myself away. I really struggled.

“I actually had planned to take my own life, then one day I was in the car with my mum driving home – we’d had a disagreement - and I just broke down in tears.

“It was a watershed moment. She was asking what was wrong but I didn’t know… I just couldn’t stop crying.

“It’s clear now I was suffering from depression, and that was about six or seven years worth of things I didn’t deal with all coming to the surface. Sport being taken away from me – as in being the best I could be, playing at inter-county level – was the final straw.

“I couldn’t understand what I was supposed to do with my life.”

Once the fog finally cleared, the answer was staring him right in the face.

********************

ACADEMIA was never high up on the agenda.

Lynch left De La Salle College after the first year of his AS Levels, repeating some GCSEs having put him back a year, meaning he was too old to play on school teams. So education was cast aside, the expectation then that no return ticket was required.

Fast-forward 10 years and it was time for a rethink. Determined to help other sportspeople who might find themselves facing a similar black hole, the ball began rolling when an access course through Queen’s University and Belfast Met led to a sports psychology degree at Liverpool Hope University, Lynch going on to complete his Masters at John Moores University.

From there, he gained experience working alongside Michael Press and Brendan Lynch at Cliftonville, while old friend and former Premier League forward, Paul McVeigh, invited him “to support the work he was doing in wellbeing and performance in football”.

“It was a long process but I found out that I could be good at academia if I took the same approach as I did when I was playing football, treating it like a performance, then seeing how far I could go.

“Once I found something that interested me, I felt invincible. It was like I’d been on an operating table and someone had brought me back to life.

“I wanted to know more about why I react the way I do, and why I behave the way I do.

Understanding yourself is your gateway to the world.”

And for all his studies and steps along the way in different parts of the world, the positive influences of key figures closer to home also helped him prosper.

“My mum started off at an entry level role in a travel agency, ended up in a director position, now she owns her own company and in 2019 was named female entrepreneur of the year. In their own right, I always got enough love and what I felt I needed from mum and dad to navigate the world.

“Then you look at someone like Paul Buchanan… every club in Ireland should have a Paul Buchanan. He is the life and soul of football in Lámh Dhearg, the constant light when there’s darkness.

“There’s other lessons you learn along the way too. When I was about 10 or 11 I went away to Whitley bay in Newcastle with a football team who were playing in a competition there. I travelled with them, but not to play.

“When I was there Jackie Maxwell – who was with St Oliver Plunkett - couldn't believe I wasn't playing so he made sure I got an opportunity… probably because they didn't have a goalkeeper with them!

“But Jackie dedicated his life to making sure young people had an opportunity to play sport, to get off the streets and learn life skills through football. Reflecting on those people, and my experiences of moving away from playing, it helped me see sport from a wider lens beyond just performance.

“People like Paul Buchanan and Jackie Maxwell, as well as other grassroots coaches and volunteers, are facilitating positive life experiences for young people who might one day make it higher. But at the bare minimum they'll have fun and a safe community in which to play sport.

“That’s what I want - to ensure sport has a positive impact on the wellbeing and experience of people who take part in sport at all levels.”

Which brings us to the here and now.

A role in the National Sports Institute of Malaysia was followed by a move to Australia Cycling, and eventually his current post working with the Australian men’s national team, U17s, U20s, U23s and the country’s para soccer team.

It is early days, but Lynch has big plans. He knows the cynicism that still exists towards his chosen field, and laughs when asked how a wellbeing manager might have been received in the Antrim dressing rooms he was part of around the early Noughties.

“PJ, Mickey Culbert… I dunno. ‘Whitey’ probably would have been open to it. He was always looking for that wee one per cent that could make the difference.

“The cynicism is frustrating on one level, but I can see where those people are coming from too, where there’s a lot of gurus and a lot of people see wellbeing and sports psychology as an exploitation area.

“It’s important that sport understands the role, the education and the training and the years it takes to get there. In elite sport, there’s always a need to be supported from a personal development point of view, including those navigating the transition beyond competing.

“My motivation was ‘if I’m going through this, somebody else is somewhere’, and if I can help through sport – which is my love – then brilliant.

“Somebody like Paul Buchanan – he gets it. He gets what it’s all about. He turns up, he smiles, and he makes 20 or 30 kids’ days at fundamental sessions. If those kids are going home smiling because they had a good time, their parents are happy… that’s why I love the GAA, love what it stands for.

“There’s nothing else like it anywhere.”