KIDS have lived through the pandemic for the best part of two years now - but many of them, and particularly the younger ones, don't really understand how viruses spread, exactly why handwashing is so important, and how the vaccines work.

So The Royal Institution (RI, rigb.org) is using this year's televised series of three Christmas Lectures to explain all about viruses, through easy-to-understand, child-friendly demonstrations.

The 'Going Viral: How Covid changed science forever' lectures will be led by England's deputy chief medical officer Professor Jonathan Van-Tam.

"The Christmas Lectures are famous for their big, spectacular demonstrations, and there's nothing like hands-on exploration for getting younger children fascinated by science," says Dr Daniel Glaser, the RI's director of science engagement.

"So we thought why not combine the two with some fun experiments that are really easy for families to do at home? Each of the experiments demonstrates a scientific process and gives an easy-to-understand explanation of one or more of the ways Covid is changing science forever.

"And what's more, they're perfect for keeping children occupied for a couple of hours during the school holidays this week..."

Here are a few of the experiments that kids - and parents - can try together...

1. DANCING PEPPER

THIS experiment uses water surface tension to demonstrate why it's easier to kill viruses when you wash your hands using water and soap.

You'll need: A shallow dish, water, ground pepper and liquid soap (washing up liquid will do).

Instructions: Pour some water into your dish and sprinkle pepper on it. Dip your finger into the liquid soap, then dip it into the water - the pepper should move away from your finger and out towards the edge of your dish.

What's going on? Water is slightly sticky - its molecules stick together, giving water an elastic-like skin on top. This is called surface tension and is the reason you can overfill a cup with water without it spilling, and why some insects can stand on water.

Soap reduces the surface tension, making the water spread out and lose this surface skin. As the water spreads and flattens, it carries the pepper along with it. Some pepper might sink to the bottom because the water's surface tension isn't enough to hold it up.

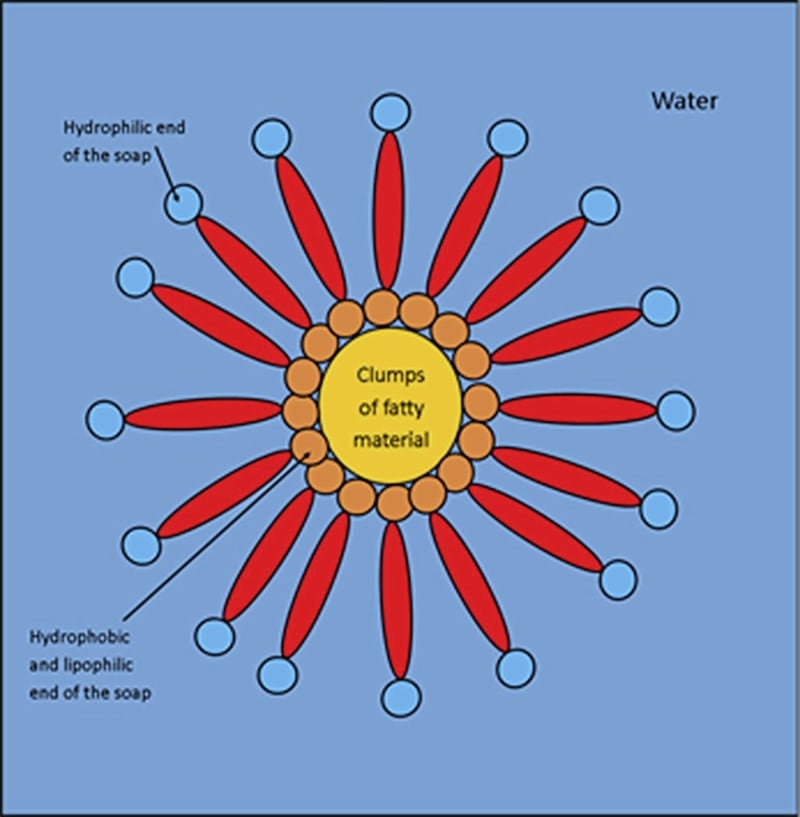

This shows why it's much easier to get rid of grease on a dirty plate, or a virus on your hands, by using soap. Grease, and the outer layer of a virus, is made of fat. Fat and water don't usually mix easily, but soap is an emulsifier, which makes it much easier for them to mix.

The soap helps to break down the grease and the virus into smaller clumps, killing the virus in the process. The soap molecules then surround these clumps, making it easier for the grease, and virus, to be washed away.

2. LET'S MAKE SNOT

THIS demonstrates how essential snot is, and how it's one of our first defences against Covid and other viruses.

You'll need: Two old kitchen paper or toilet roll tubes, tissue or toilet paper, agar powder, gelatine or Vege-Gel, 100ml cold water, 2tbsp golden syrup or liquid glucose, green food colouring, a microwave-safe dish.

Instructions: Put the water into the dish and add the amount of agar powder or Vege-Gel that the packet says is needed to set 1 pint of water. Mix together.

Put the dish in the microwave and heat in 30-second increments until it's at boiling point. Remove from the microwave, and stir the syrup in. Be careful with the hot bowl and liquid. Add a few drops of food colouring and stir with a fork.

Leave your 'snot' for 5 minutes to set a little, before stirring and leaving for another 10-15 minutes, stirring occasionally, until it looks snotty.

Rip the toilet paper into little pieces - these are your viruses - and split them into two equally sized piles. Then paste lots of snot mixture on the inside of one of the two toilet roll tubes, before standing both tubes end-up, and drop half the paper pieces in each tube.

Lift the tubes up - how many paper pieces reached the table after being dropped down each tube?

What's going on? Snot is mucus in the nose. Mucus is a mesh of proteins, sugars and water, and is a very important defence mechanism for humans.

Your body is always secreting mucus, including in your nostrils and airways. This mucus is sticky and traps particles you breathe in, including unwanted viruses and bacteria. This is one of the body's first lines of defence against infection.

Each of the tubes is like the airway of the human body, leading down into the lungs. When you drop the paper (or viruses) down the tube (or airway) with no mucus, all the viruses get through and onto the table (or into the body). When you drop the viruses in to the airway with mucus, some of them get stuck in the mucus.

Once microbes, like viruses, are trapped in the mucus, they're vulnerable to the immune cells of our bodies, which seek and destroy viruses and other disease-causing organisms. Even if the immune system doesn't capture the particles, lots of snot is swallowed and stomach acid then destroys the particles trapped inside.

Your fake snot is made of very similar components to real snot (aka mucus), with the agar providing protein, the golden syrup providing sugars, and water.

3. BLOWING BUBBLES AWAY

WHY do viruses spread more easily indoors than out? It's all about the ventilation. And with a hairdryer and some bubbles, you can prove it...

You'll need: Bubble liquid and wand, a hair dryer or fan.

Instructions: Close the windows and doors of the room you're in and blow lots of bubbles into the air of the room through the wand. Wait a few seconds, and then run through the bubbles - many will pop on you. Be careful not to slip on any bubble mix on the floor.

Now blow approximately the same amount of bubbles into the air again, and then turn on the hair dryer or fan, and blow it at the bubbles for five seconds. Run through the bubbles again. How many popped on you this time?

What's going on? Viruses can be spread between people in several different ways - one way is when an infected person coughs, sneezes, speaks, sings or breathes and particles like droplets and aerosols are sprayed into the air.

If someone else breathes in these particles or they contact someone's eyes, nose or mouth they may also become infected. The bubbles represent a giant version of these particles, and when you run through them the bubbles pop on you and you become 'infected'.

A good way to reduce risk of transmission of viruses, including the virus that causes Covid, is to improve ventilation, such as by opening a window. This means the particles stay suspended in the air for less time and you're less likely to breathe them in. The fan or hair dryer shows how this improved ventilation works - blowing the bubbles away and making them disappear more quickly.

4. SOAP: THE VIRUS KILLER

THIS is another simple experiment that shows just how important it is to use soap when we wash our hands.

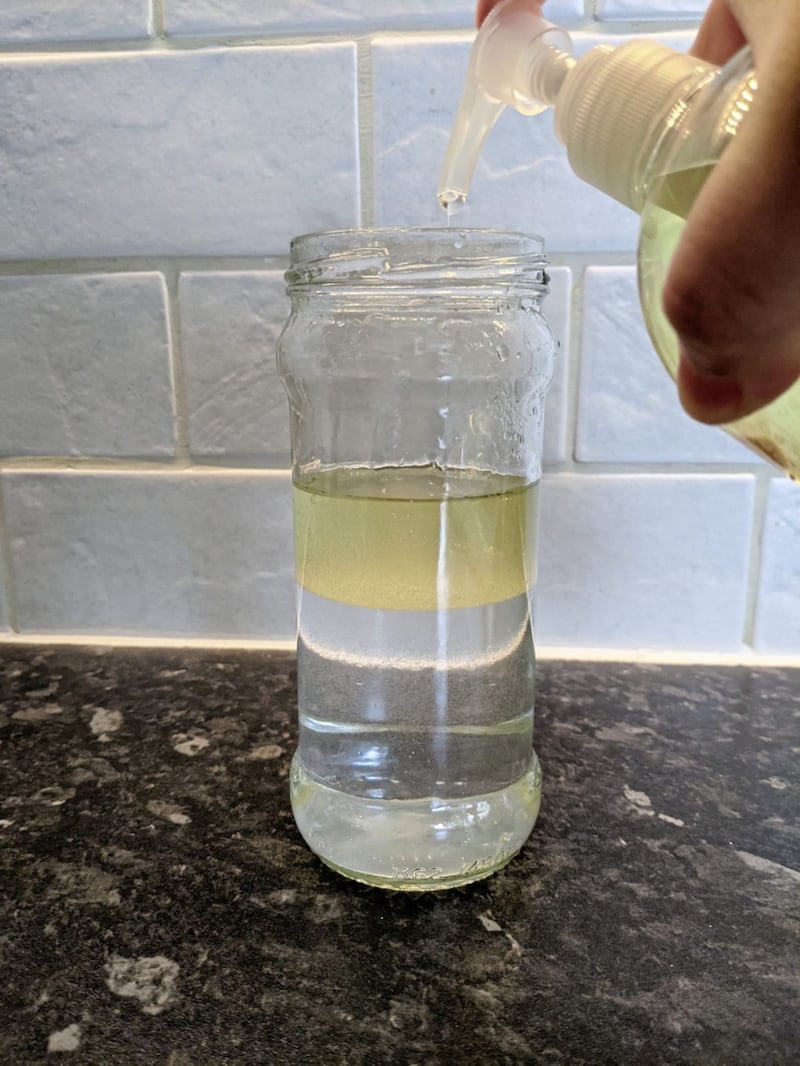

You'll need: Cooking oil, water, liquid soap (such as washing up liquid), an empty see-through bottle.

Instructions: Mix equal measures of the oil and water in the bottle before putting its lid on tightly and shaking it and then leaving it to stand. You'll see that the oil separates from the water and sits on top.

Add a few squirts of liquid soap, shake the bottle again and leave it to stand. The oil and water should now not separate.

What's going on? Lipids are a molecule that includes fats and oils. They're not attracted to water, but they're attracted to each other. Similarly, water molecules aren't attracted to lipids, but they're attracted to each other. Therefore, lipids and water won't mix.

The outer layer of a virus is made of lipids, so if you wash your hands with water only, it has no impact on the virus, because the water isn't attracted to this lipid layer. But if you add soap, the oil and water can combine.

This not only allows viruses to be washed away with water after you've added soap, but those soap molecules pull the virus's outer layer into pieces, so it can no longer infect a person.

The Royal Institution Christmas Lectures are at 8pm today, tomorrow and Thursday (December 28, 29 and 30) on BBC4.