FOR nine decades the Irish social movement Muintir na Tíre (Irish for 'People of the Land') has been embedded in rural communities across the 26 counties.

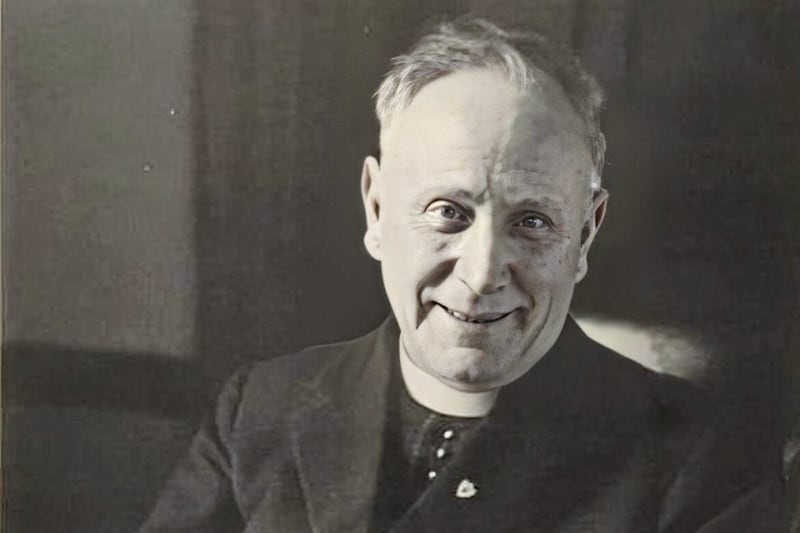

The organisation, founded by Limerick-born priest, Fr John Hayes, played a significant role in periods of the Irish state's social life in the 20th century. Its leading role in rural electrification in the 1940s modernised many rural Irish homes. Its later campaigning for Ireland’s entry into the EEC convinced many to embrace Europeanism and the benefits that conferred.

The organisation's forays over the border into Northern Ireland's six counties are perhaps less well known.

While it did not take root in the north as it did in many parts of the south, the organisation was not without its successes here.

In fact, it even had the backing of one prominent future Stormont parliamentarian.

First formed in May 1931 as a short-lived rural cooperative organisation, Muintir was an amalgam of influences whose roots were to be found in Ireland and Europe of the late 19th century.

In an Irish context, its most obvious inspiration was Horace Plunkett’s Irish Agricultural Organisation Society, which provided Hayes with a real working example of a rural cooperative.

Read more:Ninety years on, 1932 Eucharistic Congress remains a defining moment in Ireland's history

A practical blueprint was not enough for Hayes to capture the rural imagination.

Coming from a strong Irish republican family, Hayes looked to Michael Davitt’s Land League for a cultural glue which could bind Ireland’s agricultural population to the nationalist tradition.

This was partly personal, as Hayes's own family were evicted during the Land War. A 12-year period of exile from the farm saw several Hayes family members born and die in a hut provided by the Ladies Land League. Hayes took these Irish ideas and merged them with Catholic social teaching in the form of Pope Leo XIII's 1891 encyclical, Rerum Novarum, to provide an economic solution that could transcend class divisions.

When the cooperative organisation failed to take hold, Hayes, rather than give up and walk away, convened a series of weekend retreats for himself, group members and some of Ireland’s prominent Catholic social thinkers.

This was to chart a way forward in their mission to ‘save rural Ireland’.

Basing their ‘Rural Weekend’ gatherings on a French format, the ‘Semaines Rurales’ (Rural Weeks), Muintir emerged as a ‘community development’ organisation with a much wider focus.

Armed with the most up-to-date Catholic social teaching in Pius XI’s Quadragesimo Anno of 1931 (which was published exactly a week after Muintir’s launch), the new-look organisation once more reached into Ireland’s nationalist past.

Mining the community ethos of the Irish cultural revival organisations, Hayes gave Catholic teaching an Irish cultural sheen. In his own words, the new look Muintir would "work for the social, cultural and economic welfare of the people of Ireland".

For Hayes, however, this meant all of Ireland, north and south. He viewed the six counties as fertile ground for his ideas on empowering rural people without the need for government interference, in line with Pius’s teaching.

Questions, nevertheless remained. With such a Catholic nationalist outlook, would an organisation like Muintir be welcomed in the north, never mind succeed?

Hayes believed he had a trump card. Despite being guided by Catholic social teaching, Muintir, he insisted, was a Christian movement rather than a narrow Catholic one.

Indeed, the organisation had some Protestant inspiration in the form of the Danish Folk High School movement, founded by Lutheran Bishop Nikolaj Grundtvig.

Muintir's constitution even enshrined Christianity, rather than Catholicity. This stance came at a price, however, as it occasionally brought the organisation into conflict with some of the more dogmatic members of the Irish hierarchy.

Furthermore, Muintir attracted some prominent Protestant members, including Seanad Éireann member Robert Burke.

Regardless of its ecumenism, the organisation faced an uphill battle if it was to gain a foothold in Northern Ireland.

Challenges of this kind did not dampen Hayes's enthusiasm. As early as 1933 he attempted to stage one of the organisation’s ‘Rural Weekends’ in Ireland's ecclesiastical capital, Armagh.

Despite the leader's desire to establish his organisation across the border, he was cautioned against doing so at this time. He was told "the north was out of bounds, politically and religiously".

This was despite backing from Archbishop of Armagh, Cardinal Joseph MacRory. The Archbishop personally wrote to Hayes around this time, stating: "Any practical movement aiming at keeping the people on the land and making them happy there must, I believe, win the approval of every thinking man.

"Moreover, in the greater part of Ireland it is Catholic Action of the very best kind. You can, therefore, count on my wholehearted sympathy and support."

Making do with staging the next weekend gathering in Dundalk in 1934, Hayes could not hide his obsession with going further north and crossing the border.

At Dundalk Hayes exclaimed in his keynote address: "If we got 20 good men in the north, it would be in our hands for years. We are planting the seeds tonight in the northern soil."

Although Hayes maintained regular contact with a wide range of people in the north, it would take him another eight years before he seriously attempted to gain a foothold in the region.

In February 1942, while the world was at war, Hayes travelled north to promote his organisation.

By highlighting the similar situation facing rural people on both sides of Ireland's dividing line, he hoped to win support from northern Protestants. He met with rural and community groups from across the religious and political spectrum at several venues, including Queen's University.

While he had previously tried to 'plant himself' in Northern Ireland without success, on this occasion he had a man on the inside.

This was Northern Irish civil servant Gerard Benedict Newe. Newe, a public servant in the Ministry of Health and Local Government, would later join Brian Faulkner’s cabinet as minister of state with responsibility for community relations.

He was an early convert to Hayes’s ideas, and had corresponded with the rural leader for many years.

It was, however, through his work as editor of the Ulster Farmer that Newe was able to grant Hayes audiences with northern farmers and their representatives in Belfast.

The Irish priest’s northern trip was closely followed by the British and Irish press who viewed it as a diplomatic mission to establish Muintir in "the partitioned area".

Although he held many significant meetings, the main engagement was a lecture given in the legendary venue of St Mary’s Hall in Bank Street. The Ulster Herald noted that the hall was packed with 1,200 people made up of "professionals, businessmen, industrial and agricultural workers, and representatives of all shades of religious and political views".

Also covering the proceedings was the northern correspondent of de Valera’s Irish Press.

This paper had done much to elevate the Muintir leader’s profile in the south. It now claimed that the Belfast audience received Hayes as if "he was Father Mathew and Dan Ó Connell in one".

Hayes thrived in front of audiences. He had already gained a reputation as a magnetic public speaker, addressing audiences in Ireland, Rome and Argentina. Nevertheless, this was new territory.

While Muintir was anti-sectarian, it was an unknown quantity in Belfast and Hayes's words had to be chosen carefully.

In a humble, but direct appeal to those not of his faith, Hayes implored the Belfast audience to help him "build a strong rural community united in its Christian heritage".

Understanding what could be termed the sensitivities of those in front of him, Hayes proclaimed that "names and flags avail nothing" if there is no economic security. And security, he argued, could not come to any country without a strong united rural population.

Confident in his ability to deliver the message of Christian unity to a divided audience, Hayes concluded by stating, "there is a problem that I have made no reference to specifically. You all know it.

"A solution must be found, and it is for the people of Ireland to find it. Let Ireland begin to show a Christian way and we shall solve problems greater than the border."

While solving the border issue was unrealistic, Hayes’s trip bore immediate fruit. A relationship developed with members of the Young Farmers' Clubs of Ulster.

This organisation, founded in 1929 by journalist and educator, William Stavely Armour, had similar goals to Muintir's.

Several months later, the northern organisation sent a delegation to Muintir’s ‘Rural Week’ gathering at Mungret College, Limerick.

According to the Irish Independent, the Farmers’ Clubs, then led by William Rankin, were welcomed to Muintir na Tíre not as outsiders, but as kindred spirits.

Throughout the 1950s there appears to have been a more serious attempt at gaining a foothold in the north. The organisation’s monthly newsletter, The Landmark, raised hopes in early 1950 that branches would soon be established in Tyrone.

The paper argued that they would be welcome additions to the "North of the Boyne" cluster which included Monaghan, Cavan and Louth branches. A Tyrone branch was eventually established in 1953 in Carrickmore. At the branch’s dedication ceremony, the local priest and chapter president, the Rev P Hughes, PP exclaimed that Muintir was "beyond the pale of party politics and open to all."

Throughout this period Newe corresponded with Hayes from his Bedford Street offices, advising on strategies to establish Muintir in more northern parishes. Newe explained to Hayes that by engaging with "the Belfast (Protestant) press" Muintir could reach "decent people who have a genuine fear of Rome".

They were people, Newe argued, Muintir desperately needed to win over if they had any chance of success.

Hayes, by now a Canon, travelled north several times during the decade to breathe life into the organisation’s "northern campaign".

In late 1954 he attended the Ulster Council of Muintir na Tíre conference in Omagh, something which was unrealistic only a few years earlier. He also travelled to Ballymena and Cushendall, meeting with local clergy and farmers, encouraging them to grasp the nettle and establish Muintir branches.

Further inroads north were made over the next several years. In July 1955 The Landmark revealed that 44 new branches had been established in the past year, with 16 in northern counties.

While this was quite impressive, some northern branches quickly folded. While not a uniquely northern problem (many branches in the south outside of the organisation's Munster heartland also folded) the issue of partition was blamed on the disappointments in those territories.

Truthfully, by the 1950s Hayes had spread himself too thin, and long-term health problems were catching up with him. By 1956 the organisation could boast branches in England, the United States and even in Africa.

On a trip to Lancashire in late 1956 to launch the first branch of Muintir na Tíre in England, Hayes fell gravely ill. Sent home to Tipperary to recuperate in a nursing home, his condition worsened and he died on January 30 1957.

His funeral on February 1 was a national occasion. Mourners came from across the country, and even some Dáil business was suspended as a mark of respect.

Interestingly, it was noted by Hayes’s close friend and church historian, Fr John Ryan, that people from "the 26 counties, as well as admirers of very different outlooks from the six counties" came together to pay tribute to the departed rural leader.

In the aftermath of Hayes’s passing, Muintir was, for a time, effectively rudderless. Hayes was the lynchpin that held the organisation together.

With his passing, much of the interest in Northern Ireland waned. Muintir (which at times encountered severe cash flow problems), seemingly preferred to consolidate their position in the south.

Nevertheless, Hayes’s determination to bring rural Northern Ireland in line with the south in Christian harmony provides us with a fresh perspective on cross-border cooperation at a time when state level collaboration was virtually non-existent.

Dr Barry Sheppard is a Belfast-based historian and formerly the host of History Now on NVTV