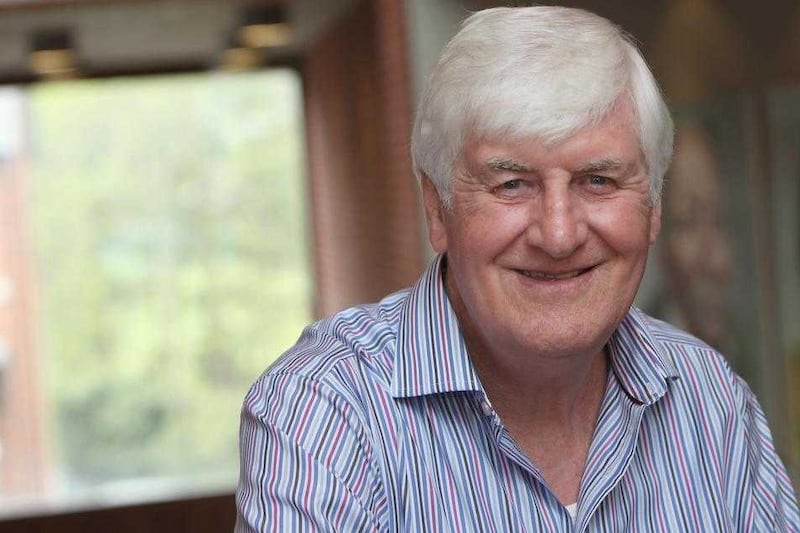

REV KEN Newell describes his late friend Fr Gerry Reynolds as “a man who came out of the future” in his memoir and, in truth, the same could be said about Newell.

A former moderator of the Presbyterian Church in Ireland, the north Belfast man formed a close friendship with Fr Gerry in the dark days of the 80s and this unbreakable bond lasted right up until the much-loved priest died last year at the age of 80.

As Newell recounts in Captured By A Vision, the pair went together to funerals of murder victims in the Falls and the Shankill in the 80s and early 90s, a time when the Troubles were in full flow and when such shows of fearless cross-community peace-building were rare to non-existent.

While Newell was brought up as a strict Presbyterian and even served as a chaplain in the Orange Order, the time he spent teaching in Indonesia in the mid-70s was life-changing.

Away from the “cramped evangelical mindset” he had developed in the deeply divided north of Ireland, his time working with and getting to know a Catholic priest in Indonesia made him come to realise that “the Catholic and Protestant churches are integral branches of Christ’s one church”, as he writes in his memoir.

He knew, on his return to the north in 1976, that he had to stop being a “passive spectator” and set out to be a peacemaker.

“When you’re a spectator, you’re protecting yourself and that’s a natural instinct,” he says, speaking to Weekend at the Lyric Theatre in Belfast. “But nobody is safe unless we’re all protected. Whenever there’s pain or sorrow or animosity around you, your community is not well.

"Being in Indonesia made me think, 'Could I do this in Belfast?’ It seemed like an answer to the plague of sectarianism and division and violence.”

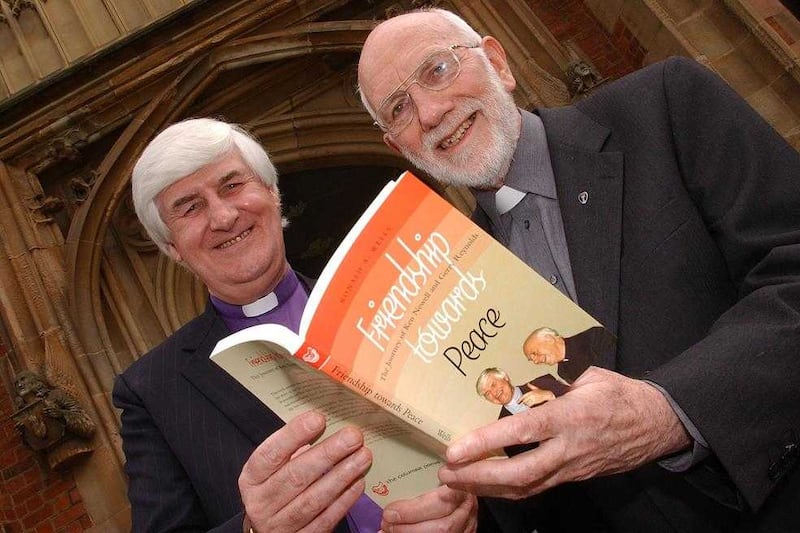

He is full of the highest praise for Fr Gerry. As minister at Fitzroy Presbyterian Church in south Belfast for 32 years, Rev Newell and his Catholic compadre were the key figures in the inspirational cross-community Clonard-Fitzroy Fellowship.

“Fr Gerry was somebody who just won his way into your heart. Fitzroy has just built a new welcome centre and Gerry had a welcome centre all around him. He was a wonderful man.

“He had wonderful sayings. One is 'When your heart is open, there’s always somebody coming towards you’,” says Newell with a hearty laugh.

“You can never tell if the chemistry is going to work, but with Fr Gerry and myself it definitely worked. He took me into the heart of the Catholic community in west Belfast and I took him into the heart of Fitzroy and the people absolutely loved him.

“I still think about him and talk about him. He was an absolute gem and I loved him dearly.”

In his book, Newell recounts a funny story about a cross-community event in the Ballynafeigh Orange Hall on the Ormeau Road, when Fr Gerry cut through any tension in the room by trying on an Orange sash.

“He was a lot of fun. When the Orangemen saw him put on the sash, they did laugh,” he says.

He writes about how one woman from the Falls Road wasn’t as enamoured with Fr Gerry and the sash and nudged him in the ribs saying, 'Father, you don’t have to go that far...’

Newell and Fr Gerry were involved in secret discussions with republican and loyalist paramilitary groups and helped contribute to the eventual IRA and loyalist ceasefires of 1994. The two were famously awarded the Pax Christi International Peace Prize for a ‘grassroots reconciliation initiative’ in 1999.

“I discovered in some of the hardest paramilitaries I ever met that deep deep down, they wanted something better,” says Newell. “They wanted peace and not violence; they wanted recognition and not being sidelined; they wanted access to an equal and fair society.

“People thought '30 years is long enough’ and thought there was a better way. Hume and Trimble and others began to frame that vision. I’ve still got hope for our country.”

And while he writes that “we are more than capable of transforming our own country”, he admits in person that “political egotism” is hindering political progress in the north.

“The peace has come but it hasn’t come with a calmness of respect for each other,” he says. “There’s still a lot of resistance and animosity and you see this in politicians who you feel can’t stand being around each other.

“When Paisley and McGuinness gave us a year of a political summer that people felt was reflecting what the future should be like, a chill factor then set in among some and that led to Paisley’s downfall.

“Politicians, educators, businesses, journalists, ministers and everybody have a responsibility to build bridges. Then you can actually start to like each other and learn about each other.

“You may not agree, but you never treat the other person’s politics as if they’re rubbish and you never treat their religion as if it’s ignorance-based, you don’t look down at them and you look into their eyes as equals. Many of our attitudes here are unhealthy and sickly. We need new attitudes.

“There’s still a chill there which is politically advantageous but emotionally disastrous for a country that wants to move forward. There are more important things than votes.”

In Captured By A Vision, the early chapters pull no punches in painting Ian Paisley as a divisive negative influence from the 60s to the 90s.

“I think Ian Paisley, at the end of his life, looked back and perhaps wished that he had been more constructive and more tolerant. He certainly stoked up the ancient fears. He made many in the Catholic community feel that they weren’t really part of his vision for the future of the country.

“But, as I say in the book, he went through a process of change and I think his best years were his last years.”

Newell’s book makes for fascinating reading. He discusses how he came to host Archbishop Desmond Tutu giving a talk at Fitzroy in the 80s, how he was in America when 9/11 happened and how being a chaplain to Alban Maginness, the first Catholic Lord Mayor of Belfast in 1997, was “a great honour”. He writes about how growing up with his Co Mayo mother brought to him a permanent affection for the whole of Ireland.

“I’m like a shamrock. Part of me is British, part of me is Irish and part of me is Ulster. I can move between those easily. I value what’s best in them all.”

There’s also an amusing anecdote about one Fitzroy member meeting Newell on Botanic Avenue and telling him “we’ve gone off you” because of his friendship with the Catholic priest Fr Denis Newberry.

Having just turned 73, Newell is happy to have published his memoir and says he wonders what he’ll do with the rest of his life.

“It’ll probably involve buying another season ticket for Crusaders FC, taking up opportunities to preach and live my life as fully as I can. I enjoy life. Inside I’m only 19.”

He refers to the book as “an unapologetic Christian affirmation of hope” and he says that anyone who follows Christ “can’t be sectarian, bigoted or racist”.

Speaking again about Fr Gerry, Newell says the friendship “brought me into the heart of Clonard”.

“As I said at Gerry’s funeral, I felt like the most hugged Presbyterian minister in the history of the Catholic Church in Ireland. So a lot of folk in the Catholic community know me and now they just call me Ken. Although some call me Father Ted,” he laughs.

Captured By A Vision is out now, published by Colourpoint (www.colourpointbooks.co.uk). Ken Newell will give a talk on his book at Fitzroy Presbyterian Church in Belfast tomorrow at 7pm (www.fitzroy.org.uk)