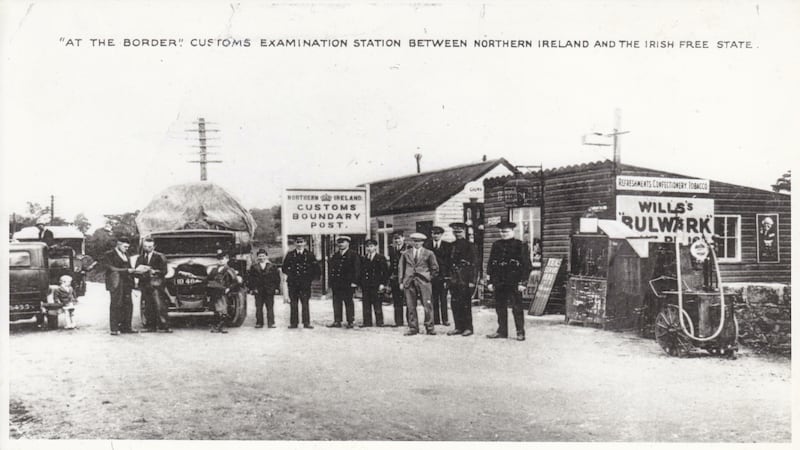

Smuggling was a feature of the land border in Ireland the moment it came into being this month 100 years ago, in April 1923, as people used all means at their disposal to avoid paying duties or to escape higher prices.

The Scotsman newspaper claimed that "Irishmen are temperamentally well endowed for that sport" of smuggling. The land border led to some very inventive, and in many cases, comical ways to avoid customs, including men dressing up as women to avoid searches, a woman eating a full cake at a customs station once she realised it was dutiable, another woman drinking a pint of whiskey at the border to avoid paying duties, and a man wearing a pair of trousers made of newspapers after discarding dutiable cloth-made trousers from a train.

One farmer, claiming he was smuggling another man’s wife in his cart, was told by a customs officer he could pass on as she was ‘non-dutiable’. Many real-life examples undoubtedly provided inspiration to Spike Milligan for his comic novel Puckoon which offers a satirical viewpoint of the impact the land border had on people’s lives.

In an article in the Irish Times in 1930, the reporter wrote on how the "introduction of duties on wearing apparel has influenced to a considerable extent the fashions among the women of Donegal. A type of what used to be known as the Ulster coat, which is long and loose, is now greatly in vogue, and it is worn on all shopping expeditions, even in summer time".

A Donegal farmer’s wife claimed that, "All the women entering Derry from this district go in as lean kine, and return resembling fatted calves. We place the garments we purchase on our bodies, tighten ourselves up as much as possible, and generally escape the notice of the officer". Due to the lack of women searchers within customs, women were considered more likely to evade capture.

While smuggling was, overall, petty in nature for the first decade of the land border, the nature of the smuggling changed considerably after Éamon de Valera’s Fianna Fáil party came into power in the Irish Free State in 1932.

By his government cancelling its annual payment for land annuities to Britain (as required under the 1921 Anglo-Irish Treaty), the British government imposed duties on farm livestock and produce from the Free State for the first time, which in turn resulted in the Free State imposing duties on UK imports such as steel and coal. The resulting Economic or Tariffs War continued by varying degrees of intensity until a trade agreement was reached between both states in 1938.

The Economic War saw a huge upsurge in smuggling, particularly of cattle from south to north. With the British imposing punitive duties of 20 per cent, soon rising to 40 per cent, on livestock imports from the Free State, prices for cattle plummeted in the 26 counties.

Smuggling cattle into Northern Ireland became a minor industry. Sophisticated syndicates sprung up using spies and decoy animals to outwit customs preventive officers. To avoid paying higher duties on livestock, false declarations were also made on the age of animals.

Customs officers were later trained on how to tell the age of cattle by examining their teeth and observing the suckling status of pigs. Many small farmers were forced into smuggling too by fear of bankruptcy or loss of farms.

For Free State farmers who paid tariffs to sell their livestock in Northern Ireland fairs, there was no guarantee of making a sale. There were many occasions of farmers returning beyond the border with their livestock but without a refund on the tariffs they had already paid. The trip had made them poorer. Records suggest that approximately 100,000 animals were walked or swam across the border in 1934-35.

Some nationalists saw it as a patriotic duty to engage in smuggling; despite political pressure not to do so, many unionists also participated in smuggling. At a unionist demonstration in Clogher in Tyrone in 1933, where the Free State was referred to as a "nation of puppets", a solicitor, WH Smith, denounced smugglers as traitors, stating that any Orange Order member who trafficked in smuggling should be expelled from the order.

Smuggling was partly allowed to become rampant as most people did not see it as a crime, with some believing it to be a lot of fun. It was not much fun for those who were caught and prosecuted, though. The repercussions could be severe, with heavy fines and/or prison sentences imposed, and the suspect items impounded.

The Daily Mail embarked on a crusade in the 1930s lambasting the British government for its feeble efforts in preventing cattle smuggling which was damaging "loyal Ulster" farmers, and recommended "a wire fence along the frontier… coupled with a strict system of visas and papers and a much larger force of customs officials".

To curb the widescale smuggling, the British government introduced the Finance Act 1934 which created a prescribed area adjoining and within 40 miles of the land border where any person in possession of uncustomed goods could be required to furnish proof that the goods were not imported from the Free State or that duty had been paid.

Subsequently, the Northern Ireland government complained that the area prescribed for proof of dutiable goods, and the searching of persons and premises relating to customs was far more wide-ranging and punitive than in the rest of the UK, mainly because Northern Ireland had the only land frontier in the UK. This provides a good early example of how Northern Ireland was treated differently to the rest of the UK due to its land border with the Free State.

More customs officers also had to be hired and both An Garda Síochána and the Royal Ulster Constabulary (as well as the B-Specials) were deployed more extensively.

With the signing of the Anglo-Irish Trade Agreement in April 1938, most people hoped there would be fewer duties and a more invisible border, decreasing the amount of cross-border smuggling as a result. While there was a big fall-off in the smuggling of cattle, the nature of smuggling changed due to the onset of the Second World War. During the war, smuggling became more prevalent than before.

With strict rationing of goods in both Irish jurisdictions, even though the 26 counties were neutral during the conflict, smuggling occurred frequently on both sides of the border.

There was widespread smuggling of household items. Many Northern Ireland residents travelled south on the ‘sugar trains’ or the ‘butter express’. Much of the smuggling was conducted by women. In one instance hundreds of pounds' worth of beauty products was seized at Dundalk Station in 1942, resulting in "girls bursting into tears when they were asked to hand over boxes of powder and lipstick of fashionable brands which cannot be bought in Britain".

While the two largest waves of smuggling occurred during the Economic War and the Second World War, smuggling has continued along the border, even after Ireland and the UK joined the European Economic Community in 1973 and the EU Single Market came into being in 1993.

In fact, some EEC schemes appeared to encourage smuggling. For some time, pigs were smuggled over and back again across the border to avail of EEC subsidies twice. Regardless of there being a frictionless border, as long as there are differentiations in prices due to currency or taxation, or availability, between the two Irish jurisdictions, there has always been smuggling.

There have been differences in the type of items smuggled over the decades depending on variations between north and south, such as on fuel, spirits, cigarettes, electrical goods, butter and eggs. Staff levels in the electrical trade south of the border more than halved from 1979 to 1983 mainly due to the smuggling of colour televisions across the border.

Each hen of one Armagh-based farmer was known to lay 50 eggs a day until the visit of a customs official reduced the number to five eggs per hen per week.

Such was the scale of smuggling that one Newry shopkeeper claimed in 1983 that "there were more Dundalk people in Newry than there were in Dundalk itself". While some with large operations made considerable fortunes from smuggling, for most people the practice of smuggling was perfectly acceptable and allowed them to make sense, and in some ways benefit, from an otherwise obtrusive border.

Cormac Moore is author of Birth of the Border: The Impact of Partition in Ireland (Merrion Press, 2019)