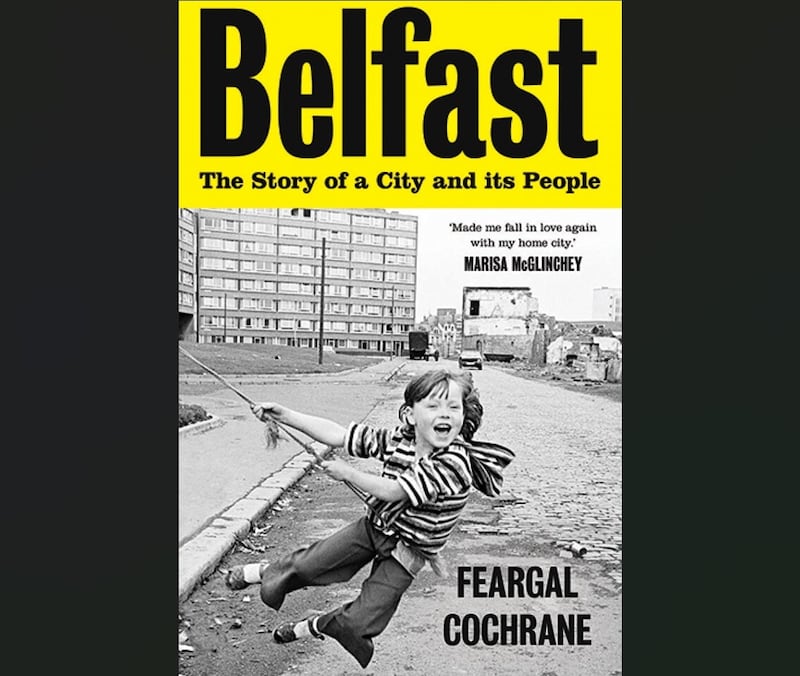

Feargal Cochrane's newly published book is described as a "lively and inviting history" that explores the highs and lows of a resilient city.

The 58-year-old, who is Professor Emeritus at the University of Kent, was raised a Catholic on the Holywood Road in predominantly Protestant east Belfast but left the north in 1998 for an academic post in England.

In Belfast - The Story of a City and its People, he tells the rich and complex history of the city, the qualities of which are often overlooked amid a focus on sectarianism and violence.

Part research, part personal memoir, the book charts the development of the city from Arthur Chichester in the early 17th century through to the present day. Notably, the author regards the era known as the Troubles, not as an exception but a "continuity and just the latest example of lots of phases of troubles".

He argues that much of Belfast's shared history, most notably that of the United Irishmen, has been hidden in the post-partition era for political purposes but that attitudes are changing.

To highlight how Belfast repressed its radical past, Cochrane contrasts the fortunes of two city centre buildings – the Ulster Hall on Bedford Street and the Assembly Rooms on the corner of North Street and Waring Street.

In the late 18th century, the latter hosted the Belfast Harpers' Assembly, while it was also where the United Irish leaders, including Henry Joy McCracken, were court martialled and sentenced to death in 1798.

"The Assembly Rooms is associated with the Presbyterian radicals who wanted self government – they were liberal, they were part of the Enlightenment and that didn't really suit the official narrative post-1921," he says.

"Arguably there should have been greater recognition of its stature, as the place that witnessed the beginnings of democratic enlightenment, rather than being left derelict or sold off to a private developer."

Read more: Feargal Cochrane: Northern Ireland –Ironic or just unfortunate?

Meanwhile, the Ulster Hall has enjoyed a prominent position in the unionist narrative that predominated for much of the 20th century.

"The Ulster Hall has strong cultural resonance among unionists due to its associations with the anti-Home Rule movement and during the protests against the Anglo-Irish Agreement, in the 1980s" he says.

The author believes that in the post-conflict era Belfast is beginning to rediscover its "invisible past". The "inconvenient complexities" that were removed to suit clear political narratives during the 20th Century, are gradually being rediscovered as the peace process has developed.

"I have a chapter in the book on tourism which is helping to connect our rich and complicated history with the opportunities and challenges provided by a post-conflict economy," he says.

"It’s a sensitive issue, as how tourism presents the past – or glosses over it – will inevitably be contested in a society that remains divided.

"Slowly the city's historical legacy is becoming more visible as figures like Mary Ann McCracken and most recently the abolitionist Frederick Douglass are being celebrated."

The change in the city's demographics is also apparent in the city's architecture.

Cochrane highlights how Belfast's post-partition architecture, and especially that of the north's new devolved parliament, sought to reinforce the unionist hegemony.

"After partition, Belfast became the capital of a country that wasn't strictly a country and one where the ruling class was very insecure – they saw the British government as fair weather friends and didn't trust them to deliver on partition. Even James Craig, first prime minister, thought it was a doomed mission, but was his duty to lead it," he says.

"I believe unionism's defensive mindset is part of the reason Stormont's the size it is and why Belfast City Hall, where the first parliament sat, was historically so reflective of a British identity –but that has been changing in recent years."

The book plots the changes that have accelerated in the city over recent decades, including landmarks like the first nationalist lord mayor in 1997.

"I've attempted to trace the transformations in the architecture of the city and how those changes are now taking place quite quickly, to reflect a much more diverse, less binary place. I believe the peace process is absolutely critical to this as well."

"Despite their well understood failings, the political institutions have helped to provide space to breathe and to understand that a deeper appreciation of other identities does not have to threaten our own."

:: Belfast - The Story of a City and its People by Feargal Cochrane is published by Yale University Press.