KNEE high to the daisies, Steven McCarthy would go out into the back yard draped in one of the collection of jerseys his father had gathered up from his playing days.

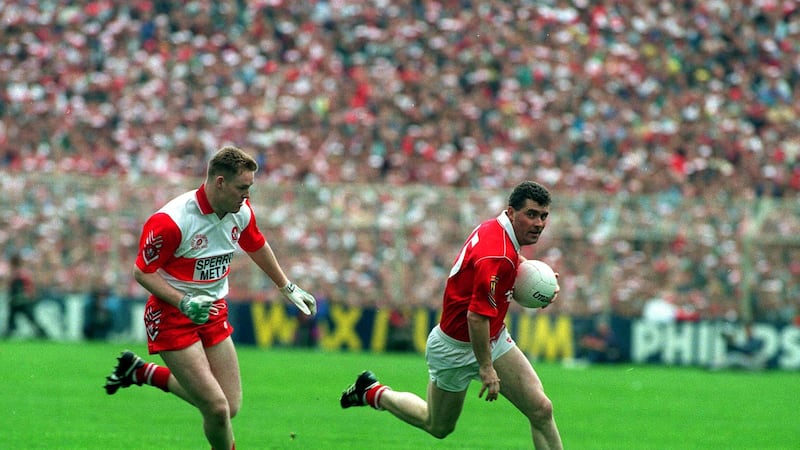

The Derry jersey always stood out to him. He’d watched the tape on repeat of his old man, Mick, behind the band leading Cork around Croke Park before the 1993 All-Ireland final.

He would captain his county in his fourth final, including the ’88 replay.

A starter in both games that year, McCarthy had kicked two vital points off the bench to swing their win over Mayo in ’89, then two more against Meath a year later before having to come off injured early in the second half.

Read More

- That was our year: Derry's 1993 All-Ireland triumph

- Unbreakable bond between Derry men who won Sam Maguire celebrated in Ballymena

- Derry's All-Ireland winner Danny Quinn on how football's challenges helped him deal with grief

As captain, he’s chasing after a perfect end to the perfect year having led O’Donovan Rossa to an unprecedented All-Ireland club title in the spring of ’93.

They'd never won a county title before it and they haven't won one since.

The Skibbereen men had beaten Lavey in a famously bad-tempered semi-final in Ballinascreen, where he scored 1-9 of his 6-60 on that run.

But come September, Henry Downey would be the man to take Peter Quinn’s outstretched hand and test the weight of Sam Maguire.

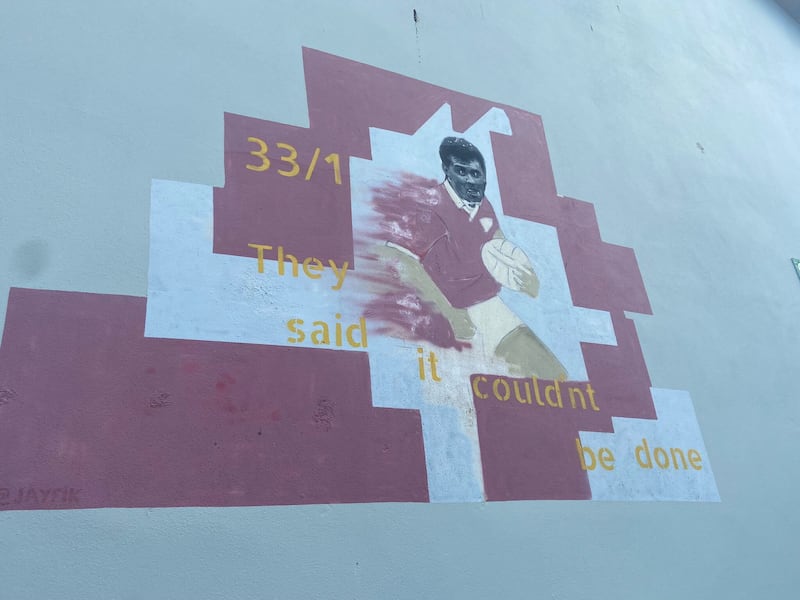

On a gable wall in the car park in Skibbereen, there’s a mural depicting McCarthy in his club’s jersey.

A town that has produced Olympic gold medallists and Oscar-winning film producers and actors, that was one of Michael Collins’ last stopping places before he was killed, it is their 1992 Cork championship winning captain whose painting is up on the wall.

“We don’t do murals down this part of the country, alright? But I’ll stroll over and take a photo of it, there’s a picture of Mick on the wall here,” says his friend and team-mate Tony Davis.

“It’s the only wall in the place that there’s a mural up on, and it’s Mick 33/1. Did y’ever hear the story about 33/1?”

The story about 33/1 is that in 1992, the bookmakers in Macroom had them priced as such to win the Cork football championship.

Half the town had money on them, players and all. When they reached the county final, there were t-shirts printed with the slogan ‘33/1, they said it couldn’t be done’.

Turned out it could be done. The phrase now adorns his mural.

After bringing the Andy Scannell trophy home and toasting it through the night, they gathered the St Fachtna’s Silver Band on to a bus with them in the morning and took it an hour up the road to Macroom.

“There’s a bronze bull in Macroom. We got off there, men staggering off, falling off the bus. And we marched behind the band into Macroom to pick up the cheque for however many thousand it was, and went on the piss for about a week.”

When McCarthy lifted the trophy after beating Nemo Rangers, he broke into an impromptu rendition of the famine ballad Dear Old Skibbereen on the microphone.

He’d sing a different verse or two each time they lifted ribbons, all the way to Croke Park and then Limerick for the replay with Eire Og of Carlow.

His controversial goal stood. Theirs, very late on, didn’t. And so he finished the song with the Andy Merrigan Cup in his hands.

“I'll be the man to lead the van beneath our flag of green,

And loud and high will raise the cry 'Revenge for Skibbereen.'”

For Steven, the warmth is in those songs and the mural, the stories and the tapes.

They’re how he knows his father, how he’s been able to build a picture of the man they all tell him he’s so alike.

In early February 1998, Mick and his lifelong neighbour and friend Jack Pat Collins were killed in a car accident on their way home from a coursing meet in Clonmel.

Steven's old man was only a young man. Just 33, around the same age he had been when his own father passed away.

More than 25,000 people attended the joint funerals of Mick and Jack Pat.

Skibbereen had lost its greatest sporting hero at that time, a limelight shared now with its rowing legends.

Helen McCarthy had lost the husband she’d known virtually all her life.

At just two years of age, Steven lost a father he never got to know for himself.

Dear Old Skibbereen was sung at his graveside on the day he was laid to rest.

The words sound altogether different there.

"And you were only two years old and feeble was your frame.

I could not leave you with your friends, you bore your father's name.

I wrapped you in my cóta mór at the dark of night unseen.

I heaved a sigh and bid goodbye to dear old Skibbereen.”

_________________________________________________

STEVEN is 27 now, talking on the phone having just left the office. He works as a Senior Business Development Officer for Newcastle United, like Cork a place gotten giddy in its footballing rejuvenation.

At 12, he captained his county’s Primary Games team at half-time in a Cork-Kerry Munster final, going on to represent the county until U16.

But by then his head had been turned by soccer.

He joined Sunderland’s academy at 16 but had his dream crushed by a series of injuries that led to his release two years later.

After coming home briefly and playing a bit for Cobh Ramblers, he went back to the north-east and Northumbria University in 2016, taking into an education that has led him back to professional football from a different direction.

“Growing up without your father is always a difficult situation, especially in terms of what I was doing in terms of my sporting career, going to Sunderland and things like that. Having a father figure like my father would have benefited me massively," he says.

“To have had his perspective on things and his support would have been so valuable to me. Obviously difficult to go through as a young fella, losing a parent at any age or not having your parent around, it’s a very difficult situation.

“It matured me, I suppose, quicker than lads my age, having to go through that all my life really, because I was so young when it happened. My family’s been so supportive, which is great.

“He was still a role model because of all the stories I’ve heard about him. The kind of man I’ve always wanted to live up to, on the pitch or off the pitch, I wanted to be as good a man as he was.

“I still live by that. Whatever I set out to do, to do my best at, and be a good person as well.”

_________________________________________________

THERE are just under 12 minutes to go in the 1989 All-Ireland final.

Anthony Finnerty has missed the chance to put it to bed for Mayo. The jitters have set in, a feeling that has become all-too familiar on the showpiece days since then.

Mick McCarthy, bearing the number 20, has been sprung from the Cork bench by Billy Morgan.

Starting numbers weren’t easily earned in the Cork inside forward line. Paul McGrath was a jinking genius. Colm O’Neill was the languid, free-taking full-forward. Dinny Allen’s there, John O’Driscoll too.

In '87 and ’89, it was John Cleary who got the number 15 shirt.

The man that has rebuilt their fortunes in the last year-and-a-bit as manager hails from Castlehaven, sworn enemies of Skibbereen.

Vying over the same spot in the Cork team, the two men had plenty of reasons not to get on.

But they were as thick as thieves, the absolute best of friends since playing together at school.

In Adrian Russell’s book The Double: How Cork Made GAA History, Niall Cahalane recalled how Mick Hegarty would drive them to training as part of the west Cork brigade.

“We had a car full of Zulus! We had serious craic. You never missed a journey because – we had two or three nights a week – you had the biggest part of four hours in the car and it was never a dull moment.”

Whatever mischief was to be had, McCarthy and Cleary were usually found fairly close to it.

“I’ll tell you one, you’ll laugh now,” Tony Davis begins.

“We’re playing Kerry below in the Munster final in Killarney, and Mick and Cleary were subs.

“Colm O’Neill was taken off at half-time and came strolling down the sideline with the runners on him, right? And whatever happened, Billy was apoplectic on the sideline, effing and blinding, and he started looking at the dugout.

“And Colm had just sat down after being taken off, and he says to the two boys ‘what did he say?’ And sure they go ‘he said Colm, get your boots, you’re going back on’.

“Colm goes up to Billy Morgan on the sideline: ‘Billy, my boots are in the dressing room.'

“‘What do you mean your boots are in the dressing room?!’ and he’s looking round and the two boys are breaking their holes laughing. You couldn’t be up to them.”

Anyway, back to ’89. His first significant touch of the ball, Mick McCarthy picks it up 50 yards from goal.

The sides are level, 0-14 to 1-11. Dermot Flanagan is on his tail but ‘Small Mick’ - as he was known locally because he was the smaller of the two Micks in his class at St Patrick’s Boys National School – glides through the gap. He scores on his right foot, the natural leg.

Cork lead. The next attack, if Teddy McCarthy slips him the pass instead of kicking the point, it’s a simple goal on.

Mayo are gone. Flanagan can’t lay a hand on McCarthy as he draws him in to attack the ball, grabs it and turns to point his second from the tightest of angles.

The trademark shift of the ball from one hand to the other almost brings a third but the left-footed shot is mishit.

Since he was a boy under the guidance of Dermot O’Donovan who helped mould them all in the school, the left was given the same attention as the right.

When Rossa won the All-Ireland club title, he scored 1-8 in the drawn final in Croke Park, kicking frees off both feet in the manner of a 1990s Shane Walsh.

“My mother always drilled into me that he was able to use both feet and when I heard that, it became something I practiced religiously, just to mimic him and copy him,” says Steven.

Cork complete the double, capping the career of the other great and recently-late McCarthy at midfield, Teddy, weeks after he’d won the hurling too.

Mick McCarthy won three straight All-Ireland U21 medals, playing three different positions in 1984, ’85 and ’86.

His first encounter with men from Derry was when St Fachtna’s, Skibbereen beat St Patrick’s Maghera in a Hogan Cup semi-final in ’82. He’d play in the All-Ireland minor final that the Oak Leafers won in ’83, but the Rebels got revenge in the U21 decider two years later.

Whether it's the years of watching the tapes of the All-Ireland finals over and over again or just that he’d inherited good hips, the shimmy came naturally to Steven in the back yard.

Football was a largely natural pursuit to both of them.

“If you did two laps of the field in a training session, Mick’d be last and he’d probably have gone around four bollards on the inside of them,” laughs Davis.

“But give him a ball in front of goal, he’d stick it in the top corner and wink at you on the way out. That’s the type of character he was.

“With the club, he kinda grew into a huge player that dragged us to that All-Ireland. There were a lot of other good players there as well but Mick was ultimately responsible. If Mick wasn’t there, we’d have no chance, or he got injured – good luck.”

The diminutive corner-forward, standing 5’10” and 11-and-a-half stone, was described by RTÉ commentator Ger Canning as “one of the finds of the year” as he swung over a score in the drawn All-Ireland final with Meath in ‘88.

The two teams had an intense dislike for each other.

Across the two games that year, Meath emerged winners as they had in ‘87 despite playing 64 minutes of the replay a man down after Gerry McEntee’s red card.

Cork swung it to complete their double in 1990. In his three games, McCarthy had savage duels with Robbie O’Malley.

It was his solo appearance at McCarthy’s funeral that went a long way towards thawing relations between the two sets of players.

Dinny Allen wrote in a local newspaper column the week after McCarthy’s passing: “Most people would know that us Cork players were never boozing buddies with the Meath players. Mick’s particular battle was against Robbie O’Malley. They crossed swords a few times like the rest of us. On Friday, Robbie arrived in Skibbereen for the removal after leaving Navan at midday. He had to be in Dublin airport at 8.30am on Saturday. His journey was tribute to Mick and the respect he had for him. Fate is a funny thing and if somebody had told me a week ago that I would be shaking hands with Robbie O’Malley in Kitty Crowley’s pub in Bandon, I would have laughed at them.”

O’Malley stayed in Barry Coffey’s house that night, and they’ve been friends ever since.

When Cork goalkeeper John Kerins passed away in 2001, a bigger Meath contingent travelled.

Half-a-dozen of them ended up walking in front of the hearse and stayed for a night that would soften the tensions some more.

“It was a great night. It was a pity that it had to take someone to die,” said Billy Morgan in Russell’s book.

The weekend Mick McCarthy died, it just so happened that Cork City were playing Derry City in the League of Ireland.

Turner’s Cross fell into stony silence in his memory before kick-off, punctuated by the church bells.

There’s beauty in the tranquillity, but so too in the noise and the laughter and the carry on.

“If I go home, there’s not a day goes by where somebody doesn’t mention a story about him or bring him up in some way,” says Steven McCarthy.

“Growing up, at times that might have been a bit difficult but looking back now, I’m so glad I was told so much about him by so many people, because that’s how I built up an image of who he was.

“Those memories I cherish so greatly because I’ve not had the chance to have memories with him, and it’s nice to have those memories he had with other people and live through them.”

When Mick McCarthy died on February 5 1998, he was still playing for the club, still starring, still unmarkable in Cork football.

Kieran McKeever marked him on the third Sunday of September ’93. Five months after McCarthy was laid to rest, McKeever was climbing the steps of Clones later that summer to lift the Anglo Celt Cup again, his career with a bit to run yet, an Allstar still to win.

That makes McCarthy's life seem so utterly incomplete.

The Oak Leaf players have always remembered and referenced him, and the sense of perspective his death gave them.

His national prominence was as a Cork footballer.

But he was an absolute Skibbereen diehard.

As he was taken to his grave, draped over the top of the coffin was the red number 14 jersey of his club.

Cork by birth, Skibb by the grace of God.

Tom Lyons, writing for the Southern Star, stopped Tony Davis after the funeral.

In the last paragraph of his piece, Lyons wrote: ‘Anthony was too overcome with grief to express his thoughts but in one short sentence he summed up Mick’s huge loss to his family, his beloved Skibbereen and his club: ‘Who will we pass the ball to now?’