ARMAGH Championship final day, 2016. Whitecross versus Tullysarran in the Intermediate decider at the Athletic Grounds.

Eugene Reavey walks out onto the hallowed turf and there’s a murmur in the stands as he makes his way towards where Whitecross are warming up.

Then, right in the middle of the field, his body hits the brakes and he can go no further, not a step.

“Oh no,” he thinks, “Is this the end?”

He shouldn’t have been there at all. He shouldn’t have been anywhere near the Athletic Grounds but – as much as any and more than most of us - Eugene Reavey lives for Gaelic Football.

He would not, could not, miss his club’s big day.

I see Eugene at the Athletic Grounds often enough to know that GAA is his passion. A deep love of the GAA was passed down from his father Jimmy’s days with the long-gone Drumharriff club to him and his siblings.

Since the night nearly 50 years’ ago when three of them were brutally murdered by the Loyalist ‘Glenanne Gang’ (which included members of the British Army, the UDR and the RUC) in their family home, GAA grounds are where Eugene Reavey has gone to find peace.

This is his story of love and loss…

Read more: A story of love and loss. Eugene Reavey Part 2

HIS hands are worn smooth. He wrings them in a constant figure-of-eight as he talks through the infamous sectarian atrocity 47 years ago. It’s a chilling tale and the telling of it brings no comfort.

But it must be told.

On Sunday evenings the Reavey family of eight boys and four girls usually assembled at their parents’ home in Whitecross, south Armagh. January 4, 1976 was different. Mrs Reavey had decided to visit her sister in nearby Camlough that evening and so the weekly get-together was postponed. If it hadn’t been Eugene would probably not be here today - the entire family might have been murdered.

Oliver Reavey, Eugene’s brother, left the family home to drive his parents and younger siblings to Camlough just after the six o’clock news on television, leaving three of the boys – John Martin, Brian and Anthony – at home.

The fire was lit, the living room was cosy and Celebrity Squares, a family favourite, was on the TV. John Martin sat opposite the fireplace, Brian was in an armchair and Anthony was sitting on the arm of it. Seats were always at a premium.

Then the door opened…

“Our house had an open-door policy all my life,” Eugene explains.

“Anybody who came in was very welcome. When the door opened the boys could see this gun over the top of the door – the barrel had holes in it, it was a Sten gun.

“The next thing this boy started to shoot. John Martin was right in front of him and he was shot; one, two, three across his chest. He fell onto the ground and he (the shooter) put a magazine into him, that’s 43 or 44 bullets.

“Then Brian was shot in the back and the bullet came out through his heart and he had a few more bullets in his back and he fell onto the fireplace dead. You would have thought, when you saw him, that he was just sitting there.

“Anthony went and dived under a bed and the gunman went up after him and stood on the bed and riddled him (down through the mattress) and left him for dead. Anthony had 17 bullets in his groin area and none of them hit a vital organs.

“The gunmen went back into the kitchen and they shot off all the doors in the house looking for the rest of us.”

THE Reaveys were targeted purely because they were a Catholic family, a nationalist family, a GAA family.

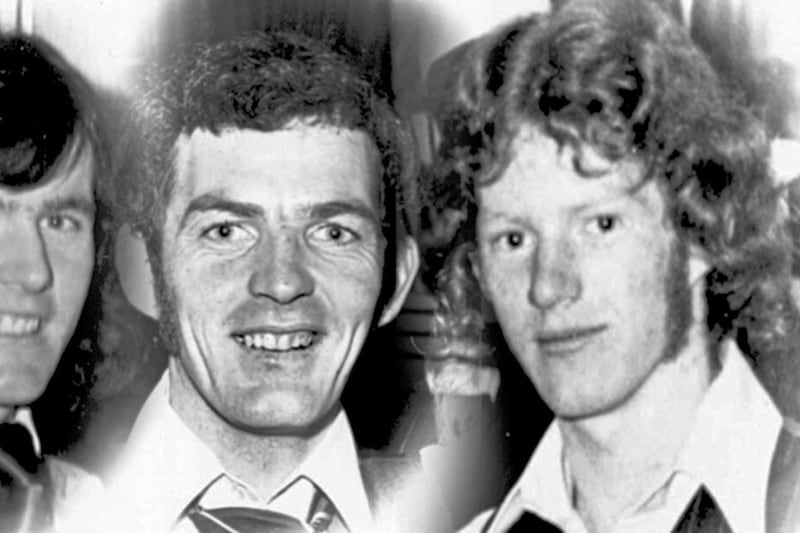

The three brothers at home that night had all lined out for Whitecross. John Martin had been an underage player, Brian had played for Armagh at minor and U21 level (Joe Kernan was among his team-mates). Anthony, then 17, was already playing midfield for his club.

Eugene had played throughout the 1960s until a ruptured stomach prematurely ended his career.

“Football was a matter of survival then,” he says with a laugh.

“I remember playing in Poyntzpass one Sunday and that night the team went to a guest tea in Omeath. Every one of us had a black eye or a tooth knocked out or something.”

Read more:A story of love and loss. Eugene Reavey Part 2

He was 12 when he travelled to Dublin in the boot of a car to watch his first All-Ireland final in 1960 and he hasn’t missed one since.

“We had to stop in every town we went through because the radiator was boiling up,” he recalls.

“You couldn’t put cold water into it, you had to stop at a house and get a kettle of boiling water.”

He went to watch Crossmaglen in the championship that same year and he’s been to all their games since too. Except one.

“I always liked the way Cross played football, it was different football they played,” he says.

“I missed one match – the 2000 All-Ireland final against Na Fianna – because my wife went and booked a trip to New York for St Patrick’s Day.

“I had to go. I was going up the street following these bands and I saw an Irish pub. I went straight into it and watched the match and I might as well have been in the pub in Whitecross.”

All his children were christened on Saturdays.

AFTER the carnage an uneasy silence descended on the house that night in 1976. Anthony Reavey lay under the bed until he heard the gunmen drive away. Shot to pieces, he crawled out. He passed Brian and felt for a pulse, there was no pulse but he didn’t think his brother was dead because of how he was sitting upright on the fireplace.

He saw John Martin butchered and then crawled outside and went a couple of hundred yards up the road to Pat O’Hanlon’s house. He pulled himself up and banged on the door and, when Angela O’Hanlon and her son came out he said: ‘I’m shot, everybody’s shot’. Then he passed out.

The O’Hanlon’s phoned the police, the ambulance and the doctors.

When Oliver Reavey returned home from dropping his mother off in Camlough he parked outside the house and walked in to discover the horrific scene. The front door was lying open and the first body he saw was John Martin’s.

“He was lying there – cut in two – and Oliver got an awful shock, he never spoke for maybe 12 months after it,” says Eugene.

“There was no such thing as counselling or anything like that – if the soldiers had got you up the road they would have kicked the shite out of you, that’s all the counselling you got.”

ON the Saturday morning, the day before Whitecross played in the Intermediate Championship final, Eugene had a heart-attack.

The day before the final! He couldn’t believe his bad luck.

From his hospital bed he implored the doctor: “Hi boy, get me fixed-up here, we have a championship match, the final of the championship, in Armagh the marra’.”

The doctor was having none of it. He told him to be quiet. There would be no football for a while. Eugene needed rest, he said, and rest was the only thing on the menu.

“Mrs McKeever (Ciaran McKeever’s late mother) looked after me in the hospital,” says Eugene.

“God she was a great woman, and I was taken upstairs to the ward and there was tubes in me all over.

“The next day at lunch-time Roisin (his wife) came in and brought me some things but when she was hoking in the locker didn’t she take my clothes home with her. At two o’clock I said to one of the nurses: ‘Would you get me a smart TV and I’ll go into a wee room and watch the football’ because I could get it on Armagh TV.

“She says: ‘You are not allowed any stress, you have to lie there, you’re not even allowed to listen to it on the radio’. I pleaded with her… no good.”

BLOOD and bullet holes and two men dead. Father Con Malone, who was home from the African Missions, rushed to the house he knew well and, after doing what he could there, drove the couple of miles to where Eugene lived.

“Normally he was a jolly fella but the minute he came in through the door I knew something was wrong,” Eugene recalls.

“He says: ‘Throw your coat on Eugene, there’s been an accident over at the cottage’. I said to Roisin (Eugene’s wife): ‘I’m away over to the house, I’ll be back in 10 minutes’.”

On the way to the ‘home place’, Eugene asked Father Con what had happened and the priest told him there had been a shooting and he thought there might be one fatality.

They arrived at the scene to find two policemen barring their way at the front door.

“They said: ‘You can’t get in’,” Eugene recalls.

“I fired them out of my road. John Martin was lying on the floor and I was down kneeling beside him saying a bit of a prayer and the next thing, out of the corner of my eye, I saw this policeman hoking through the china cabinet. People hadn’t much in them days but my mother was very proud of her bits and pieces of china. I says to him: ‘What are you at?’

“He says: ‘I’m looking for ammunition, I believe that there’s ammunition in this house’. I said: ‘Well unless you’re going to plant it there’s nothing here’ and myself and my cousin Kevin Reavey, who was only about 14 at the time, fired him out through the door.”

Read more:A story of love and loss. Eugene Reavey Part 2

THROW-IN time for the Championship final (4pm) was drawing ever-closer and Eugene did his best to resign himself to missing it but he could not contain himself and the remarkable chain of events below unfolded.

He got out of bed.

“I put my hand into the locker to get my trousers but I had no trousers,” he explains.

Mrs Reavey had taken them home. But, trousers or no trousers, Eugene was going to the match.

“I pulled all the tubes out and got my slippers on me,” he says.

“I went out and down the stairs, I was bare from the waist up.

“I asked the fella at the desk to ring me a taxi. He says: ‘Where are you going?’ I said: ‘I’m going to the football, that’s where I’m going’.”

EUGENE’S brother Seamus and their father Jimmy were faced with the grim task of going to Daisy Hill Hospital in Newry to formally identify the bodies of Brian and John Martin.

On the way there Jimmy Reavey “took a bit of a turn” and so heartbroken Seamus was left to go to the morgue alone and put names to his murdered brothers’ corpses.

The following day the press arrived en masse at the rural house. Helicopters hovered overhead as the UDR, the British Army and the RUC lurked on the roads and in the hedges.

TV reporter Ivan Little interviewed Jimmy Reavey who somehow found the strength and dignity to appeal for calm and say he wanted no retaliation for the murder of his sons.

“Our boys were being labelled as terrorists but our boys were in nothing – not a thing,” says Eugene.

“If they had have been (in the IRA) I would have put my head down and walked away but our boys were in nothing and I said to myself: ‘If it takes me the rest of my life, I’ll never let these boys (their killers) off with this’.

Little told the family he would take the interview with Jimmy to Belfast and have it broadcast on the 5.40pm news bulletin and the Reaveys gathered around the television that evening to watch it before they got in their cars to drive to Daisy Hill and bring home the remains of Brian and John Martin for the wake.

They left after the bulletin never thinking that another horrific scene lay in their path. Eugene was driving the front car on that dark, wet evening when a man on the road ahead waved his arms for him to stop on a hill near the crossroads at Kingsmills.

CONTINUED ON MONDAY