Over Easter, I sat down to write a letter.

My writing is appalling. Even with a new fountain pen, it still looks like our house spider has run wild over a blob of spilled ink.

It was not always so. In school, learning joined-up writing was a rite of passage. You left the babies’ classes and grew up behind a wooden flip desk with an ink well.

We used pens with crude metal nibs to dip into the ink, then spent hours scritchy-scratching our cursives.

I could never emulate the copperplate script of my parents. And times moved on and along came shorthand and computers and my ability to write legibly dashed off and hid itself in a dark nook, just like our house spider.

I blame Teeline. Now my husband laughs when I hand him a card. He opens it and reads aloud like Bill and Ben the flowerpot men... then requests a quick translation of the scrawl.

The problem is that we rarely write letters these days. Emails are easy. Tippy-tap, tippy-tap, I sit here at my laptop. It’s double speedy. I’m an 80 words a minute woman.

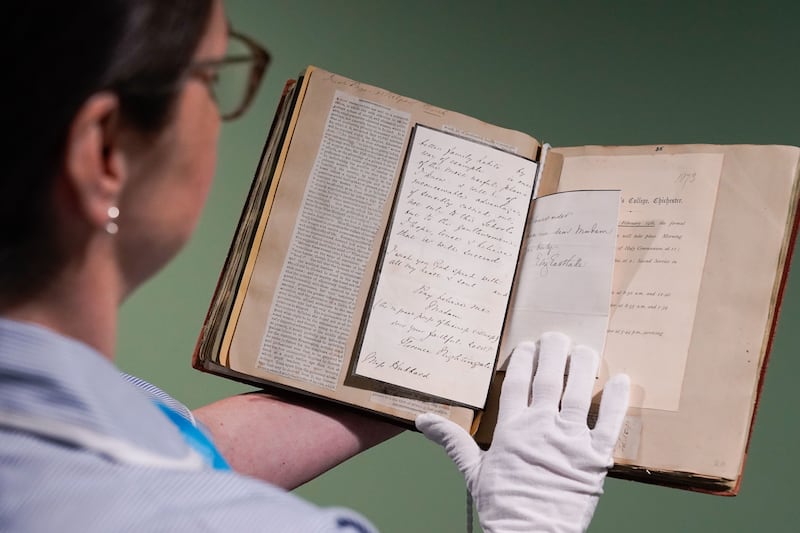

But technology has come at a price. Who cleans out a drawer 20 years later and comes upon the treasure of an old email? The physicality of a letter remains when the writer is long since gone.

Who cleans out a drawer 20 years later and comes upon the treasure of an old email?

In the drawer beside my bed, I keep a few treasured letters. One from my father written shortly before his sudden death when I was 26. It’s a letter about everyone at home. It’s funny, drawing me back to the comfort of the familiar – what my brothers and sisters are doing; my mother.

The paper is light and crisp as onion skin – Basildon Bond blue; the script flowing beautifully courtesy of his fountain pen.

When he died, I inherited his pen. Maroon and silver, chubby but neat in the hand. I still can’t make my handwriting as artistic as his.

The other letter is from my mother – a funny letter, warning me not to spend all my student grant in Mirror Mirror.

Their love reaches out from the pages, drawing me back to carefree times when we were all there together, when tea was on the blue formica kitchen table at 5pm and the rosary was at 7.30pm and if a friend called, well they could get down on their knees and join in too.

Those were the days when aunts and uncles sent birthday cards with a 10 shilling note inside.

My little sister once followed my aunt around all day after she received a letter from her daughter in the post. She had tucked it into her housecoat pocket to read later.

“Open it quick,” said my little sister. ”You never know, there might be money inside.”

And my aunt laughed and laughed.

But in the not so very long ago, letters were all people had. Now more than 7,000 letters from emigrants to North America have been collected.

Guardian journalist Rory Carroll writes that the letters tell of Pennsylvania coalmines, Minnesota winters, Boston slums and the desperate struggle to adapt and survive – and to make peace with the likelihood of never seeing home again.

US historian Kerby Miller gathered the material over 60 years and you can access it now via the University of Galway website.

The letters celebrate the freedoms of life in America – owning land or a shop; not having to doff your cap to a landlord or obey a priest. For some it was the American dream – but not for all.

Those letters home were read and re-read, folded and tucked in an old envelope and stored in a drawer.

They remain when the writer has lone since gone… a touchstone to the person they were, a testament of love.