The Sunningdale Agreement, which was signed 50 years ago at the weekend, could conceivably have saved thousands of innocent lives if it had been allowed to remain in place, and deserves to be remembered as one of the most tragic lost opportunities of modern Irish history.

It was rightly regarded as an historic breakthrough, introducing the concept of power sharing at Stormont for the first time in a way which had all the potential to allow the development of a fair, just and peaceful society here.

However, the refusal of many unionists to accept the basic principle of partnership in government, and the determination of loyalist and republican groups to maintain their appalling and entirely futile paramilitary campaigns, left the new structures in a highly vulnerable position.

They were eventually brought down in 1974 by the naked intimidation and violence associated with what was known as the Ulster Workers' Council strike, with the full support of key figures in the two main unionist parties.

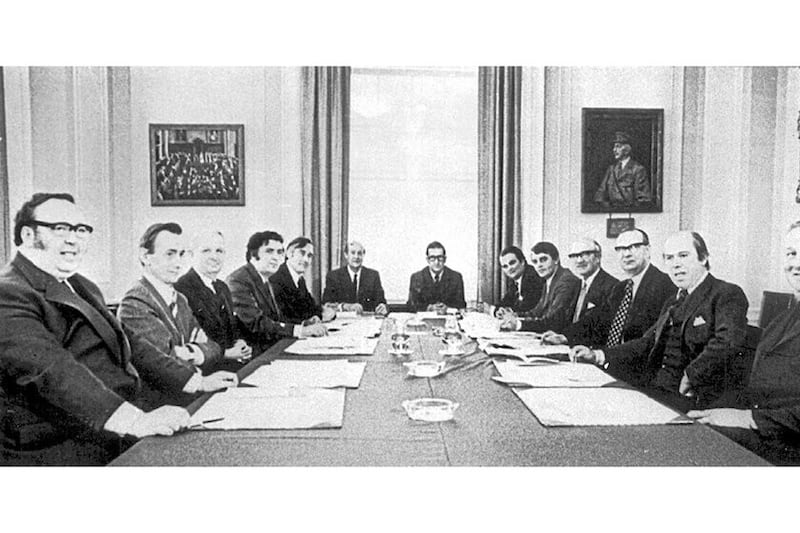

While there are different opinions about what constituted the start of the Troubles, the death toll began to rise steadily from 1969 and was already approaching the 1,000 mark when after intensive negotiations the Sunningdale Agreement was finalised at Berkshire in the south of England on December 9, 1973.

It was endorsed by both the British and Irish governments and established a Council of Ireland, a Stormont assembly and a power sharing executive which included members of the Ulster Unionist Party, the SDLP and Alliance, but, even though Sinn Féin was not involved in electoral politics at that stage, it was still bitterly opposed by negative elements within unionism.

They could argue that they were given a mandate for their stance by the UK general election of February, 1974, when, during a period of turmoil , anti-agreement unionists won 11 of the 12 Northern Ireland seats, but destroying the Sunningdale pact still turned out to have disastrous consequences on all sides.

Although it was possible to veto progress for a while, the 1998 Good Friday Agreement, famously described by Seamus Mallon as Sunningdale for slow learners, eventually restored power sharing, with the main difference being that Sinn Féin was by then at the heart of the process.

The Troubles are thankfully now no more than a dark and distant memory, but it is fair to conclude that many of the 3,500 people who eventually died might well have survived if Sunningdale had been allowed to stay in place.