AFTER my first big cycling trip in May a friend asked me: “What was the single best thing about it?”

Ooh. I had to think. There was so much. I thought of the hills and seascapes of Galloway, the sandstone farmsteads and market towns of Northumberland. Of all the woods and moors and winding roads and bridges. Ferries on the Rhine. Medieval churches. Ship-shape gardens. Bunkers. Battlefields.

I thought of Dutch camper-vanners invariably offering me a beer or a hammer to peg my tent. All were grey-haired like me, squeezing in a quiet trip before the school holidays. I thought of windmills and of pollarded willows, mile upon mile of them along the banks of rivers and canals. Of glimpsing domesticity as I rolled by on cycle paths along back fences.

I thought of Antwerp’s half-kilometre-long cycle tunnel under the River Scheldt, opened in 1933 - yes, near-century-old cycling infrastructure, Ireland! - and of stumbling upon Rubens masterpieces in that bustling city’s empty cathedral.

I recalled a comedy breakfast in a B&B, effing and blinding about burnt tomatoes that would have made Basil Fawlty blush clearly audible from the kitchen.

Was it brewing coffee by a Scottish stream? Or cycling through a storm of thistledown near Van Gogh’s birthplace? Or how a bike can reduce the distance between strangers: “Where are you coming from?” “Where are you going?” “Sounds crazy. I’d love to do something like that.”

You see? It’s hard to pick a single thing.

There was one three-way web call, though: me, all excited, about to dock in Holland on the overnight ferry from Newcastle; my wife, working at her desk-cum-kitchen-table; and our daughter, halfway to Belfast on the school bus.

And I have to admit that, even though the point of my trip was to swap the virtual reality of computer-centric life for the physical realities of new places and sensory experiences, it wouldn’t have worked without technology.

The internet enabled live commentary from beautiful stretches of countryside, which my family at least pretended to be interested in. It allowed for help with homework from far-flung cafés and facilitated, given good enough WiFi, real-time games of international backgammon.

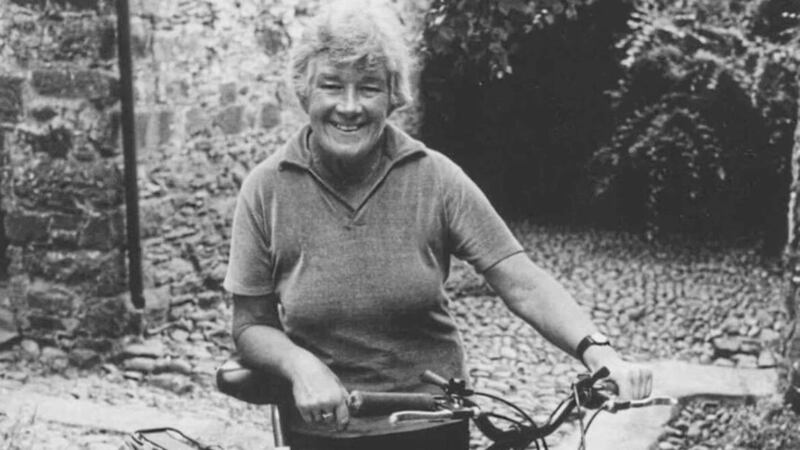

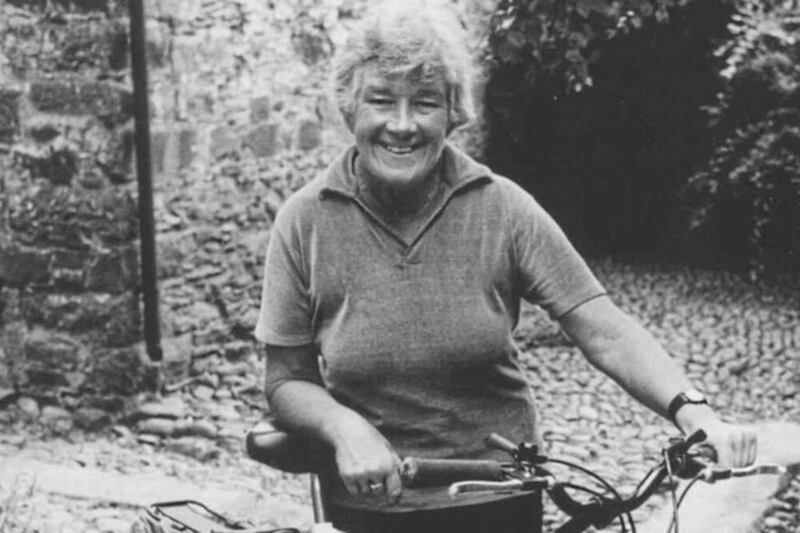

It also meant I didn’t need to carry books. In a downmarket hotel in Rouen I read the news that travel writer Dervla Murphy had died. And although I’d read Full Tilt, her debut, years before, I downloaded it there and then and read it again.

I felt resonance in her description of how lark song had made her homesick as she traversed a desert in Iran; cycling the back roads of Picardy, with its vast, dull-green expanses of unripe wheat and rapeseed, I’d found the sound of skylarks bitter-sweet; it called to mind the uplands of Ireland, and I longed for their variety of colour, their wildness.

Incidentally, Ms Murphy’s first night in continental Europe on her two-wheeled odyssey to India was spent in… the Rouen Youth Hostel.

But the female lead in my own cycling drama was a voice in my head, intermittently, from the moment I set off each morning until I rocked up at a campsite or a maison d’hote in the evening. (And no, it wasn’t the Virgin Mary.)

“Take the next left,” she’d say. “In one hundred yards turn left. Now turn left.”

Or, and more often than I would have liked: “You have left the original tour. Now make a U-turn.”

However sympathetic Dervla Murphy might be to viewing a machine as company – she wrote about her bike, Roz, as if it were a character, after all – I imagine she would disdain cycling-navigation apps, as I had previously done myself.

But the number of roads and volume of traffic have increased enormously since she set out 60 years ago, in January 1963, so staying off the beaten track, the central tenet of bicycle touring, is more complicated now. And although my jaunt across Britain, the Low Countries and France was comparatively small beer, to safely and enjoyably navigate the route in analogue would have required more maps than practicable, more time than available.

It came as a surprise to find that the English-language voice on my app was posh northern Irish. So while sat-nav woman wasn’t exactly me oul’ mucker, there was a certain homely reassurance in her cool bossiness.

She led me up the garden path a couple of times, mind. In Normandy, when my options at one juncture were to ford a waist-deep river, risk a rotting footbridge or backtrack a mile uphill on a gravel lane, her advice, given with the detached certitude of poshos everywhere, was: “Now go straight.”