THERE’S a scene in BBC Two’s Couples Therapy, featuring real American couples who have inexplicably agreed to be filmed while confessing their innermost desires and traumas to a therapist, when one of the male partners asks “why would I put myself in an uncomfortable situation?”

“Because you want to know reality,” therapist Dr Orna Guralnik replies.

The man looks confused, as if the idea of wanting to know reality hasn’t entered his head before.

Reality is perhaps a wrong choice of word. One person's strong exchange of views is, after all, another person's screaming match.

Perhaps the better question is: is it better to know or not know?

According to an Institute of Irish Studies-University of Liverpool/The Irish News survey, when it comes to the Troubles around 40 per cent of people want the latter.

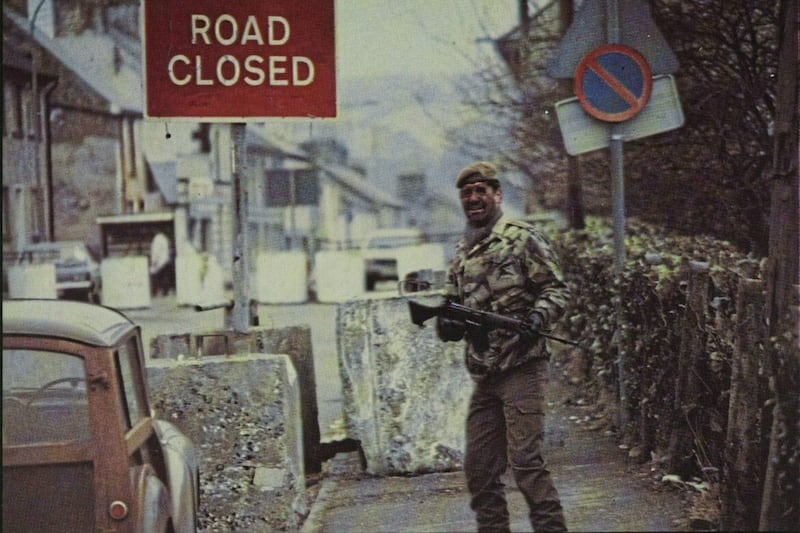

That 40 per cent of people support the British government’s proposals for a blanket Troubles amnesty - what Boris Johnson referred to as allowing Northern Ireland to “draw a line under the Troubles”.

An amnesty, the legislation for which has still not been put before Westminster, would see an end to all prosecutions, legacy inquests and civil actions related to the conflict.

For victims’ groups, the idea that those who killed their loved ones can live on without facing the possibility of justice is abhorrent.

A truth recovery process, for want of a better phrase, has been proposed by government. But this seen as toothless and insufficient by victims’ groups.

Notably, the survey did find that almost 70 per cent of respondents agreed there was a requirement to deal with the legacy of the conflict.

But there's the rub. In the 24 years since the Good Friday Agreement, no overarching strategy has ever been agreed.

It seems extraordinary that it is now more than 13 years since the Eames/Bradley report recommended a legacy commission.

At the time, Lord Eames said Northern Ireland needed to take a "final step out of the conflict by dealing with the legacy of the past”.

That report might have been our best chance to properly address legacy issues.

It did not propose an amnesty for crimes linked to the Troubles but recommended the legacy commission should propose how "a line might be drawn”.

Headline costs of £300 million and recommendations of a £12,000 payment for families of all those killed - including those of paramilitaries - overshadowed the report.

Now we’re not much further on than we were in 2009.

Other countries have faced the same struggles in wrestling with the past.

As Pedro Almodovar’s masterful film Parallel Mothers has highlighted, Spain still cannot agree on how to deal with unhealed wounds from its fascist history.

Spain spent years trying to blot out the legacy of General Franco’s dictatorship, which saw tens of thousands of people murdered in the early years of his regime. A 1977 amnesty law managed to push back the past for a few decades but it never went away.

The unwritten "pact of forgetting” only lasted as long as the exhumation of the first mass grave in 2000.

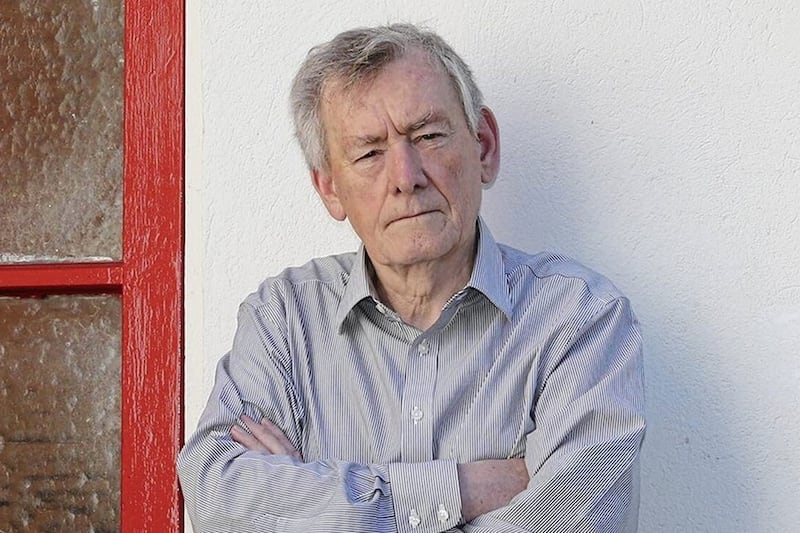

It was telling when Alan McBride, from Wave trauma centre, said last week that “the people that matter mostly here are victims and survivors”.

For victims’ families, a line can never be drawn. Their grief is only compounded by confusion and uncertainty over what actually happened.

Mr McBride suggested the wider roll-out of a process similar to Operation Kenova - the criminal investigation into whether the RUC failed to investigate as many as 18 murders in order to protect the IRA double agent known as Stakeknife - would go a long way to helping families.

"We work with many of those families at Wave and those families have had answers to those questions,” he said.

It's fanciful to think that any society can definitively deal with the past. Grief and hurt tends to linger and affect later generations.

Many victims' families have spoken of the impossibility of getting over the circumstances of their loved ones' deaths.

But it is essential that they receive answers and, if possible, justice.

It doesn't really matter if 40 per cent of people want a line to be drawn under the Troubles.

That can't happen until we as a society agree a way forward - even if it puts us all in an uncomfortable situation.