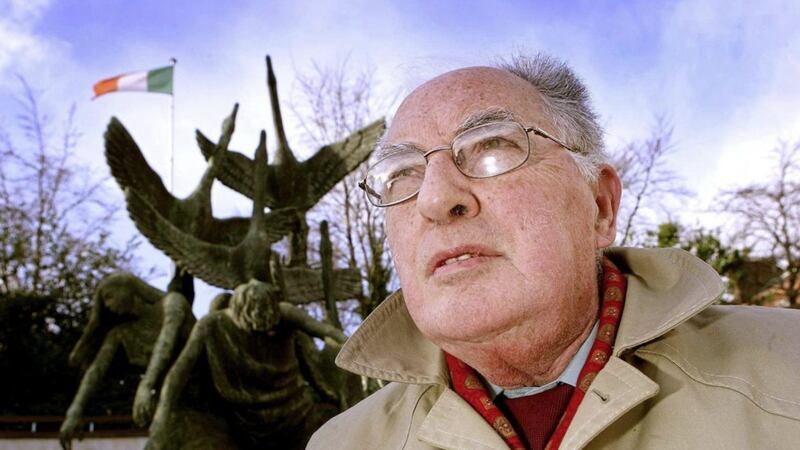

Almost 50 years ago—on October 24, 1971—Ruairí Ó Brádaigh, then president of Sinn Féin, addressed the party’s Ard Fheis and set the aim of an ungovernable Northern Ireland as a prelude to a united Ireland.

Last Friday I listened to a couple of young people from what I describe as the neo-loyalist, post-1998 Good Friday Agreement generation set out their aim of an ungovernable Northern Ireland as the prelude to an eventual border poll.

Ó Brádaigh favoured instability because he believed it would encourage the British to pack their bags and go. Indeed, a month later Labour leader Harold Wilson outlined a fifteen-point plan of transition to a united Ireland as part of his party’s solution to the ‘Irish problem.’ The young loyalists, on the other hand, argued that instability and “worsening relationships between unionism and the Irish government, as well as between unionism and nationalism in Northern Ireland,” would undermine support for unity from voters in the Republic.

There has long been a view within unionism that Sinn Féin has never had an interest in proving that Northern Ireland can work; because proving it could somehow undermine their insistence that it is an ‘illegitimate statelet’. Gerry Adams’ response to the GFA beefed up the view: ‘The Agreement is, therefore, not a settlement, but is a basis for advancement. It marks the beginning of a transitional period towards Irish unification, but only if all those who express an interest in that objective, especially the powerful and the influential, move beyond rhetoric to build a real dynamic for national and democratic change. It was never and will never be enough to say that the nationalist nightmare has ended when it quite clearly has not.’

Perhaps he believed—and still does—that any evidence of Northern Ireland transforming into a consensual, cooperative example of genuine power sharing would make it more difficult to promote unity at all costs. Let’s face it, if things looked settled on this side of the border wouldn’t there be a temptation for the political establishment and voters on the southern side to leave well enough alone and not tempt fate by pushing for a border poll anytime soon?

But Adams and key players in Sinn Féin and in the IRA didn’t spend their lives campaigning to end British rule just to finish up in an executive with the DUP (officially launched in the Ulster Hall a week after Ó Brádaigh’s address) proving that Northern Ireland could be governed perfectly well, thank you very much. ‘Normal’ never suited Sinn Féin interests. Ironically, of course, the law of unintended consequences meant that the DUP’s attitude to Adams meant that ‘normal’ wasn’t part of the DUP’s strategy, either: which made it much easier for Sinn Féin to continue to play the ‘failed state’ card at every opportunity.

Yet, as the two young loyalists suggested, there are circumstances in which the ‘ungovernability’ of Northern Ireland cuts both ways. At some point—and I still believe a border poll is inevitable—voters in the Republic will be asked to make a call on whether they want to embrace Northern Ireland and build a ‘new’ Ireland. Their vote will be steered by their response to a single question: do the advantages of uniting Ireland and accommodating upwards of 800,000-plus unionists/loyalists/Orange et al (the vast majority of whom will probably have voted NO) outweigh the potential disadvantages?

It’s actually a question I haven’t heard anyone from the pro-unity side ask yet. There is lots of talk from them about the health, economic, education etc benefits of unity, but very little about the cultural/identity/accommodation benefits to unionists; let alone the impact of party-political unionist votes/agenda on the government in a ‘new’ Ireland. Indeed, will there be a mandatory role in government for unionists in a ‘new’ Ireland: or even a veto on a range of issues which might be considered of particular importance to them?

Those things (power sharing and an ‘Irish dimension’, for example) were deemed essential for nationalists in Northern Ireland from 1974 onwards. Wouldn’t something similar be deemed essential for unionists in a united Ireland?

Fifty years on from Ó Brádaigh’s argument that unity depended on the ungovernability of Northern Ireland, it may now be the case that the perception of ungovernability could be a massive turn-off for voters in the Republic. I wonder if Sinn Féin has considered the point and, if so, what their response will be.

For those two young loyalists I have another question: if ungovernability puts off voters in the Republic does it do anything to attract British support for Northern Ireland? An interesting little conundrum.