NATIONALISTS like myself who advocate a non-violent approach often have a difficulty with the past.

Most of us who took part in the events marking the centenary of the 1916 Rising, for example, would be in favour of the contemporary peace process.

But those who initiated Easter Week a century ago were unapologetic about choosing the rifle over the ballot paper.

There was no prospect of military victory and that must have been obvious to most participants.

Indeed if it hadn’t been for British foolishness in executing the leaders, the whole thing would have been just another doomed patriotic endeavour.

There is an argument that commemorations are a bad idea because they incite a fresh generation to take up the gun.

However, the 1916 centenary was observed in a measured and dignified fashion by the Irish government and I am not aware of any accusations that it generated support for paramilitary violence.

This year marks the 150th anniversary of the 1867 Fenian Rising. The level of commemoration has been very modest by comparison: Google tells me Sinn Féin’s Mary Lou McDonald is speaking at an event at Hugginstown, Co Kilkenny, on Friday evening; there is also a seminar on the Fenian Rising at the National Archives in Dublin on Saturday morning.

But then Easter Week was ultimately a political success because of the executions, whereas a more lenient approach was taken with the Fenians.

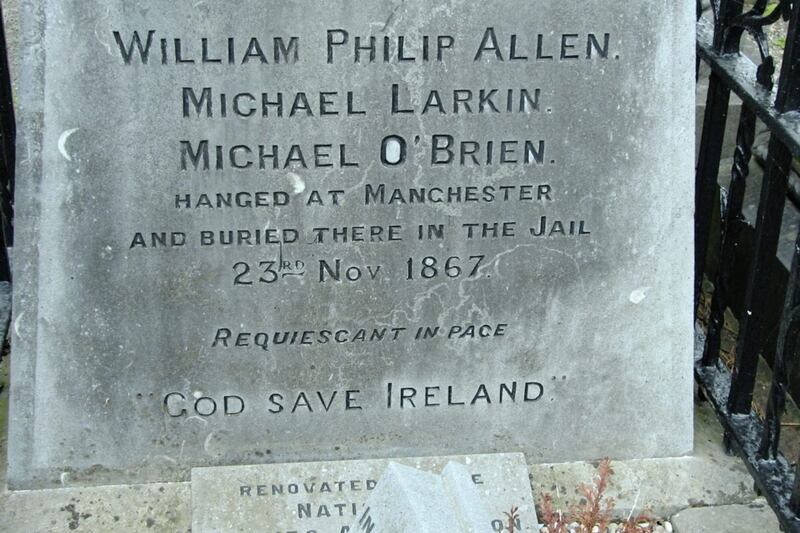

There were three prominent exceptions: I refer to the Manchester Martyrs, whose 150th anniversary occurs this week.

“Allen, Larkin and O’Brien”, as they are known in song and story, were publicly hanged on November 23rd 1867; the first Irish political executions since 1803 when Robert Emmet was hanged, drawn and quartered.

The Manchester episode has acquired a special resonance for myself since I was told of a family connection with one member of the trio: Michael Larkin from Lusmagh, Co Offaly - where he is to be remembered in a series of events this coming weekend.

I was informed that an aunt of mine by marriage, who died six years ago, was a direct descendant of his.

This impelled me to take a look again at the entire episode. They were part of a group of about three dozen who attacked a police van at Manchester’s Hyde Road on September 18 1867.

The intention was to free two prominent Fenians, Thomas J. Kelly and Timothy Deasy.

Sergeant Charles Brett, who was guarding the prisoners, was shot dead in the incident, apparently by a bullet fired through the keyhole.

Charges were brought against 26 men and three of them ended up on the gallows: William Allen was only 18 years old; Michael Larkin was 31, a tailor by trade with a wife and four children; Michael O’Brien, 31, from Cork, had served in the American Civil War and attained the rank of lieutenant.

We are told Larkin was unwell at the time of the incident and Allen and O’Brien were helping him to escape when all three were arrested.

Larkin’s speech from the dock ended with an old saying: “What is decreed a man in the page of life he has to fulfil, either on the gallows, drowning, a fair death in bed, or on the battlefield.”

Whereas the trial was a rushed affair, the Offalyman’s execution turned into a long-drawn-out agony because the rope was not properly fitted around his neck.

A reporter from the Manchester Examiner wrote that, “Larkin died very slowly, and his prolonged struggles were shocking to behold”.

However, the objective of the Fenian operation was achieved. Kelly and Deasy were freed and escaped to New York, despite a reward of £300 being offered, which was a colossal amount at the time.

Friedrich Engels, close associate of Karl Marx, said they had “accomplished the final act of separation between England and Ireland”: “The only thing the Fenians had lacked were martyrs. They have been provided with these.”

Three weeks after the hangings, a bomb was planted at London’s Clerkenwell Prison in an attempt to free another Fenian activist.

The result was that 12 people were killed, 120 injured and nobody escaped; another Fenian, Michael Barrett from Ederney, Co Fermanagh, was later executed.

Marx, who was living in London at the time, observed: “The London masses, who have shown great sympathy towards Ireland, will be made wild and driven into the arms of a reactionary government. One cannot expect the London proletarians to allow themselves to be blown-up in honour of Fenian emissaries.”

It’s a familiar pattern: a harsh and brutal action by the British authorities arouses widespread sympathy for the Irish cause, but then an atrocity involving innocent civilians crushes the solidarity back to virtually nothing.

The Manchester Martyrs said “God save Ireland”, after sentence was passed, but sometimes “God help Ireland” seems more appropriate.

@ddebreadun