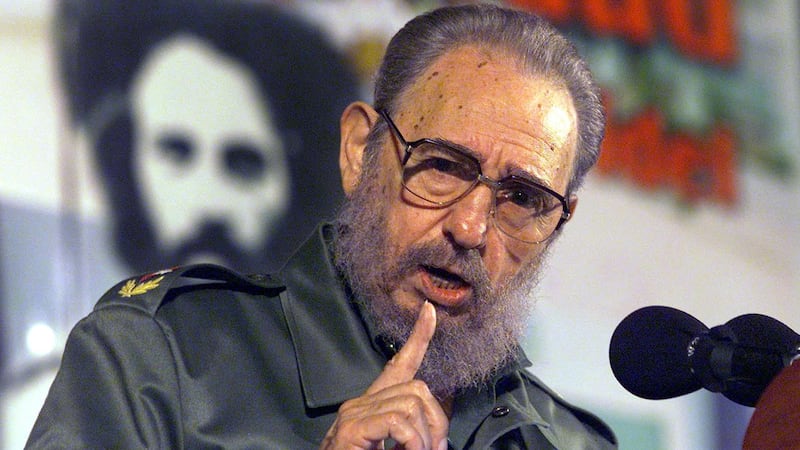

IT seems safe to assume that, as he approached his death, Fidel Castro made an assessment of the 90 years he spent on this earth.

He doubtless felt satisfaction at having overthrown the Batista dictatorship, crushed the US-sponsored invasion at the Bay of Pigs and kept that neighbouring superpower at arm’s length for half-a-century before his brother Raul took over.

When brought to trial after an early and unsuccessful venture into armed struggle, Castro declared: “History will absolve me.”

He was a man who had a huge radicalising impact and, with Che Guevara also to the fore, the Cuban leadership was way ahead in the glamour stakes.

No wonder so many young people in Latin America and elsewhere chose revolution as a career option.

In the last analysis, what did Castro and his friends achieve? There was undoubted progress in education, health and other spheres. Some may quibble about the details but nobody can dispute there were fundamental gains.

But before granting absolution we have to take full account of the negative aspects, otherwise those who criticised the statement issued by President Michael D Higgins after Castro’s death will come after us.

Irish republicans greatly appreciated his outspoken support for the hunger-strikers in 1981, but people have died in the same manner protesting against the Cuban regime.

We are told, for instance, that Francisco Aguirre Vidaruetta died in September 1967 “protesting the use of the same colour uniform for political prisoners and common criminals”.

Sounds very familiar. I have come across 13 names of dead Cuban hunger-strikers from the 1960s to the current decade, but there may be more.

Civil liberties or rather the lack of them remains a serious problem. Nobody would label Amnesty International as a tool of imperialism but that organisation is scathing in its criticisms.

But Amnesty is banned from Cuba since 1990 – what we Irish might call “an illegal organisation”.

The present writer visited Cuba in 2003, as part of an invited group of journalists, with a view to describing the positive achievements of the revolution.

But there was a major news story at the time which I was, rather reluctantly, obliged to cover.

Seventy-five critics of the regime, including journalists, were convicted of anti-state activities and given sentences ranging from six to 28 years.

Adding to the drama was the fact that a number of their trusted colleagues turned out to be secret agents of the regime and testified in court that the dissidents received money and office equipment from the US government.

Among those jailed was poet and journalist Raul Rivero, who got 20 years. His wife, Blanca Reyes, agreed to talk to me but, since she suspected her home might be under surveillance, we agreed to meet at a café in downtown Havana.

Halfway through the interview, she indicated that two men who had sat down at a nearby table were members of the security police who were spying on her.

One of them had a carry-bag which bulged suspiciously as though it contained a recording device.

Blanca Reyes answered all further questions with her hand placed over her mouth so that the two men could not hear.

Initially a strong supporter of the revolution, her husband could no longer tolerate the restrictions on free speech and became disillusioned. Aged 57 at this stage, he was facing two decades behind bars.

When we left the café, the two fellows at the next table also departed. A man who appeared to be the café manager gave me a look on the way out that still haunts me, as if to say: “How could you do this to me?”

In fairness to the Cuban regime, had this been North Korea I would presumably never have gotten to meet a dissident’s relative, not to mention another regime critic, Vladimiro Roca, whose father was Communist Party leader Blas Roca.Transmitting my article back to Dublin proved to be a problem as I could not get a direct electronic link and ended up “bouncing” it through Colombia where I had been covering the trial of three Irishmen accused of assisting the FARC guerrillas.

Happily, Raul Rivero was freed from prison with a number of other dissidents at the end of the following year and moved to Spain. Diplomatic sanctions by the European Union were seen as a key factor in securing the releases and all 75 were out within eight years.

We should not forget that the hostile attitude taken by successive US administrations contributed to the climate of oppression in Cuba.

President Obama’s restoration of diplomatic relations was a positive move but the new arrangement is under threat with the coming advent of Donald Trump to the White House. The story is not over yet.

@ddebreadun