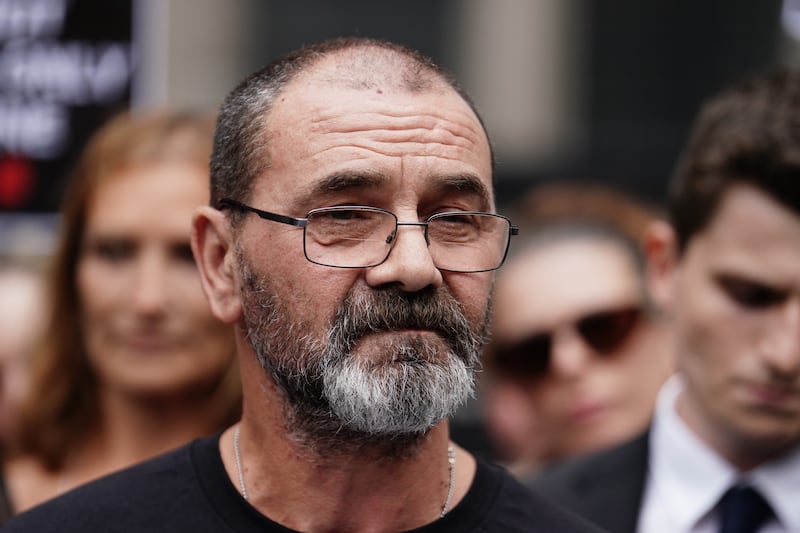

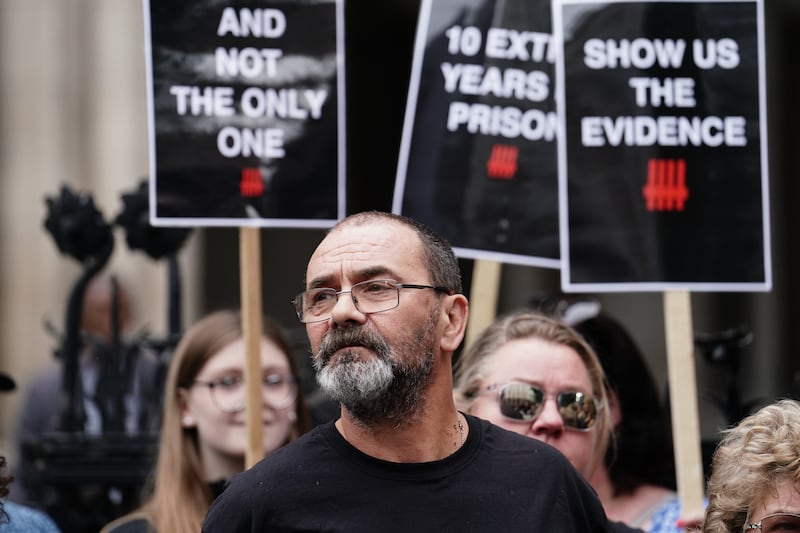

A man who spent 17 years in prison for a rape he did not commit has accused the body responsible for investigating potential miscarriages of justice of having an “attitude problem”.

Andrew Malkinson, 57, had his 2003 conviction for the attack in Greater Manchester quashed by the Court of Appeal last month after DNA potentially linking another man to the crime was identified.

He had twice applied for his case to be referred for appeal by the Criminal Cases Review Commission (CCRC) but was turned down.

He was eventually released from prison in December 2020.

The CCRC announced on Thursday that a leading barrister, with extensive experience prosecuting and defending cases, would lead a review of its role in the case.

It would focus on the CCRC’s decisions and actions relating to Mr Malkinson’s two applications to the body.

The announcement comes after CCRC chair Helen Pitcher met Justice Secretary Alex Chalk on Wednesday and discussed the issues in the case.

But Mr Malkinson said he only found out about the review through media coverage.

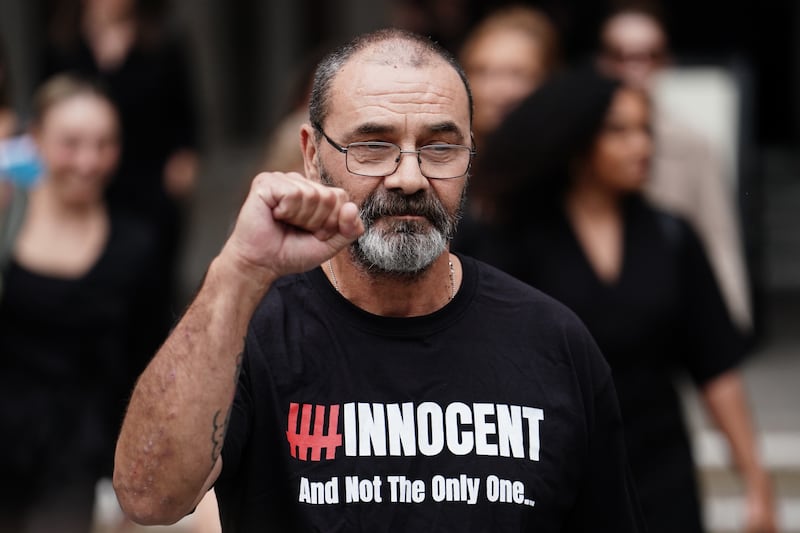

“The problem at the CCRC is attitude,” he said in a statement released on Friday.

“They were set up as an independent body to investigate suspected miscarriages of justice.

“They are misconstruing independence as being independence from the prisoners like me applying to them, rather than independence of the agencies that wrongfully convicted us.

“CCRC have not communicated with me since my conviction was overturned.

“We found out that they were launching an inquiry into my case from a journalist because she had received a press release.

“That is the attitude problem, right there.”

After Mr Malkinson’s release, advances in scientific techniques allowed his legal team to provide new DNA analysis that cast doubt on his conviction to the CCRC, which then commissioned its own testing.

A new suspect was identified in 2022, whose DNA had been on the national database since 2012.

Case files obtained by Mr Malkinson as he battled to be freed show that police and prosecutors knew forensic testing in 2007 had identified a searchable male DNA profile on the rape victim’s vest top that did not match his own.

No match was found on the police database at the time and no further action was taken.

There is no record that they told the CCRC, the body responsible for investigating possible miscarriages of justice, although the Crown Prosecution Service said Mr Malkinson’s lawyers were told.

Notes of a meeting between the Forensic Science Service, the CPS and Greater Manchester Police (GMP) in December 2009 included a note that the DNA had been found in an area of the victim’s vest top that was “crime specific”.

Mr Malkinson applied to the CCRC for a review of his case that year, but when the review concluded in 2012, the commission refused to order further forensic testing or refer the case for appeal.

CCRC documents relating to the case between 2009 and 2012 suggest there were concerns about costs.

Mr Malkinson’s solicitor Emily Bolton, founder of the legal charity Appeal, said the “CCRC is currently the wrong people asking the wrong questions in the wrong places”.

She added: “You cannot solely rely on a state agency to mark the state’s homework – lawyers for the wrongfully convicted need to be able to access the evidence as well.

“CCRC’s investigation advisers are ex-police, their executives are barristers, their previous chair was a prosecutor and the current chair appoints judges.”

She said investigative journalists had the skills the CCRC needed, “not barristers and judges” whose expertise “should come last, when all the facts have been uncovered”.

“With only half the facts, case decisions will always be flawed, whether at the CCRC level or in the Court of Appeal,” she said.

The CCRC is an independent body and its website stressed that it did not work for the Government, courts, police, prosecutors or anyone applying for a review of their case.

James Burley, Appeal’s investigator on Mr Malkinson’s case, said: “Flawed CCRC decisions can only be challenged by judicial review, which is expensive and ineffective.

“A new, free and independent tribunal is needed to ensure flawed CCRC decisions can be scrutinised and challenged by those seeking to clear their names.”

On Friday, Professor Graham Zellick, the former chairman of the CCRC, said the “workload has gone up very considerably” since he stepped down in 2008 but that “the funding hasn’t risen commensurately”.

He told BBC Radio 4’s Today programme: “There may or may not have been mistakes in this tragic case, but they can be investigated, the facts can emerge and decisions can be taken.

“(The) Government bears considerable responsibility for diminishing in many ways the role and capacity of the commission, and that needs to be looked at.”

On Thursday, a CCRC spokesperson said: “A review into the decisions taken in Mr Malkinson’s case couldn’t be started until we had the judgment from the Court of Appeal, but we have long recognised that it would be important to have one.

“We will be as open as we can be within our statutory constraints with the findings of the completed review and the lessons to be learned.

“This is a complex case in which many elements have informed the decisions taken.

“We recognise that Mr Malkinson has had a very long journey to clear his name, and it is plainly wrong that he spent 17 years in prison for a crime he did not commit.

“We have already been in touch with Greater Manchester Police and with the Crown Prosecution Service to offer our assistance in any of their enquiries.”