It is hard to talk about Hugh Russell in the past tense. In all my time, I don't think I have ever met anyone who was more full of life, and who brought so much positive energy to everything that he did, so it is difficult to believe that we have lost him.

When we try to consider what made Hugh such an exceptional person, I think that in our tough and complicated world there is for once a very simple answer and it all comes down to love.

Hugh loved his family, he loved sport, he loved his work and in return he was loved by essentially everyone he encountered to a quite astonishing degree.

The life story of Hugh Gerard Russell, which is a remarkable record of achievement and affection, began on December 15 1959 in Stanhope Street, in Belfast's Carrick Hill district, although the family subsequently moved to Duncairn Parade, which was very much their home place.

He was the son of Hugh senior and Eileen, and the brother of Sean and Frankie, and he was educated at St Patrick's boys' primary school in North Queen Street, where his teacher, Jim McGarry, father of the future Irish News managing editor Fiona McGarry, picked him out from the start as as a bright and capable pupil, and remained a close friend.

Hugh then progressed to St Patrick's College at Bearnageeha on the Antrim Road, a famous Belfast institution, and he was always very proud to be a 'Barney Boy'.

His boxing career took him around the world but his most significant destination was in north Belfast, at the old Sunflower Bar on Corporation Street, where the celebration was held when he returned from the Moscow Olympics in 1980, as it was in the course of the evening that he met the love of his life, Kathy.

[ Hugh Russell funeral hears he was 'role model and inspiration' to manyOpens in new window ]

Hugh was always a quick worker and proposed after only three months. They got married on September 15 1986 and they were blessed with the arrival of Hugh junior, Hayley, Megan, who was still born, and then James and Calum.

Hugh's entire life revolved around his wife and children, and, although his sporting and professional commitments were very demanding, his day always began and ended at the centre of his universe in Skegoneill Avenue.

The pride his family took in his accomplishments was immense, because they knew that, although Hugh was the most modest of individuals, he was, it is probably fair to say, Belfast's best known and best loved resident.

His legend should really have started when he became officially eligible to join the Holy Family boxing club near his home at the age of 11, but he had actually fibbed his way through the front door some four years earlier.

When Gerry Storey, the godfather of Irish boxing and Hugh's great mentor, is the witness you know it can only be true that Hugh, from the age of seven, insisted he was old enough to box, only to drop out when the championships came round every year, claiming he had the flu, because his real date of birth would have emerged.

After finally reaching the legitimate age of 11, although still weighing in at below four stone, he proceeded to win every title across Co Antrim, Ulster and Ireland, and repeated the trick annually as it emerged that a very special boxing talent had arrived.

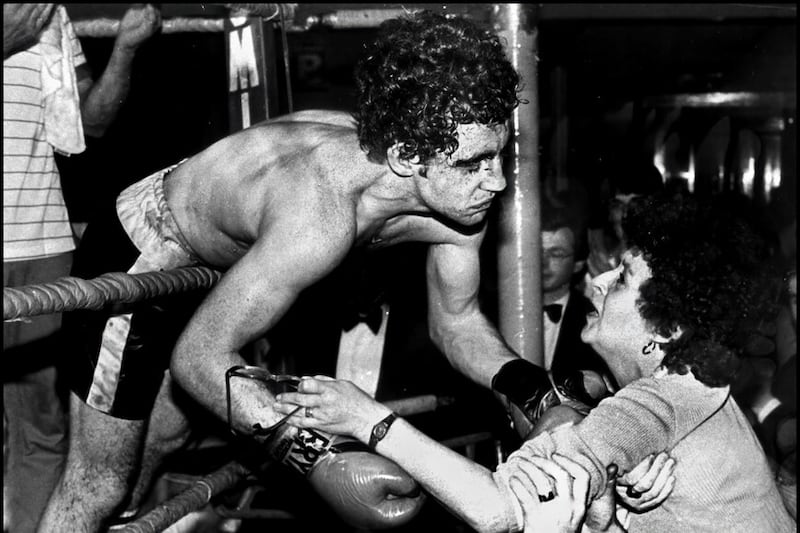

He became a Commonwealth and Olympic medalist, to incredible acclaim, before reaching even greater prominence by graduating to the professional ranks as the protege of the late Barney Eastwood.

It's almost impossible to describe the sheer excitement which surrounded those Eastwood promotions in the early 1980s, but, even four decades later, people are still talking about them.

Hugh's contests with Davy Larmour have passed into our sporting fabric, and the friendship of the two gladiators managed to transcend their epic rivalry.

Only in Belfast could the defeated Davy volunteer to drive the victorious Hugh to the Mater Hospital so they could both be patched up after the fight.

Anyone who wants to get to the essence of our city's dark humour needs to listen to Davy's tale of how he was placed behind screens in the ward, and examined by a doctor who looked at his many cuts and asked, "Who did that to you?" before Davy pulled back the curtain and pointed to Hugh, who was waiting his turn on the other side, announcing "He did".

When Hugh retired from boxing and became a press photographer, it's no exaggeration to say that he was pointedly reminded of his win and, equally bluntly, his subsequent loss against Davy in the course of practically every marking he attended for the rest of his days.

Read more: Hugh Russell and Davy Larmour relive the fights that electrified city's boxing scene

It's a measure of Hugh that he rose above all that to become just as well known in journalism as he was in sport, because he was so brilliant at every aspect of his job and delivered one outstanding image after another for The Irish News.

Perhaps his most celebrated shot immortalised Gerry Conlon bursting out of the Old Bailey in London with his sisters in 1989 after his wrongful conviction was finally overturned.

It was not down to luck but to the cuteness needed in talking his way into a nearby building site where a friendly foreman recognised Hugh and allowed him to pose as a painter for hours before he was in the right place to capture among the most compelling news photographs of our era.

He also cared about ordinary people wherever he went, as was demonstrated when he was part of an Irish News group which travelled to Africa and joined a Children in Crossfire initiative to focus attention on the famine in Malawi in 2002.

His striking pictures helped to raise tens of thousands of pounds in donations from our readers, but, before he came home, he had given away all the possessions and cash he brought with him to the starving children he encountered, and he eventually boarded the plane with nothing left other than the clothes he was wearing.

Hugh touched so many lives along the way, and was quite simply a force for good in everything that he did, so it is difficult to believe that there is now a vacant desk in The Irish News and an empty chair in his family home.

I want to acknowledge that, in our office, we also lost Dawn Egan this week, because Hugh and Dawn were great friends, they sat beside each other, they were the first people into the building every morning and your day was always going to get better when you saw them.

A round of applause as Hugh Russell passes the Irish News building for the last time pic.twitter.com/5u32F7RkBG

— Jane Corscadden (@janeinator) October 18, 2023

Our days are not going to be the same again, so our sympathies go out to Kathy and the entire Russell family and we will cherish our memories of Hugh.

It all does come down to love in the end. Hugh gave and received love in everything that he did and along the way he made our world a better place.

Hugh Russell explains how he captured the image of Gerard Conlon leaving the Old Bailey a free man: