The confidence and supply deal signed by the DUP in June 2017 with British prime minister Theresa May ended in acrimony. But many thousands of homes and businesses have high-speed broadband because of it.

During 2016 research for what it called Project Stratum, the DUP gathered detailed maps of Northern Ireland’s broadband blackspots, rural communities included. It ring-fenced £150m of the dowry extracted from Theresa May for propping up her minority government. The contract, won by the Fibrus company, will continue until 2025 but already significant work has been done.

The DUP can justifiably claim a role in transforming broadband availability. The part it played in the IRA going away is an achievement of profoundly different importance.

Twenty years ago next month, General John De Chastelain returned late from witnessing an unconvincing session of weapons decommissioning by the IRA. His honest testimony at a Hillsborough Castle news conference holed David Trimble and the Ulster Unionist party below the water-line. The DUP taunted the UUP mercilessly over how republicans were toying with them. In Assembly elections the following month, the DUP won 27 seats to the UUP’s 24, Sinn Féin returned 24 MLAs compared to the SDLP’s 18 and the political landscape was primed for change.

The backlash over the Northern Bank robbery in December 2004 and the murder of a brave, entirely innocent Belfast man, Robert McCartney, in January 2005 made untenable the co-existence of Sinn Féin and the IRA.

The DUP, fronted by Ian Paisley and managed by Peter Robinson, had their own non-negotiable pre-conditions for engagement. One stipulation required Sinn Féin to publicly pledge its support for justice and policing. The decision was taken at its Dublin ard fheis in January 2007. Four months later, the first DUP/Sinn Féin-led power-sharing administration took office.

At some future time, the decade of flawed politics that followed may be viewed in a more benign light. The participants were attempting to operate an untried, mandatory coalition model. They were expected to set aside tribal suspicions and hostilities while knowing that, at election time, they would have to compete and undermine each other in order to survive.

Miraculously during those years, the killings on the streets stopped.

Then came the phase of non-engagement that continues to this day. Stormont closed in 2017 after Sinn Féin pulled out of power-sharing. It was followed by the second phase of deadlock, initiated by the DUP, in May 2022.

On October 13 the DUP will assemble for its annual conference. The party remains the dominant voice of unionism. It claims that its support base backs the stance of staying out of Stormont until more favourable terms on post-Brexit arrangements are in place.

But the DUP has reverted to being a party of protest rather than a party in power. The contrast with Sinn Féin is striking – the largest party in Stormont and Dáil Eireann and pushing to lead the next Irish government.

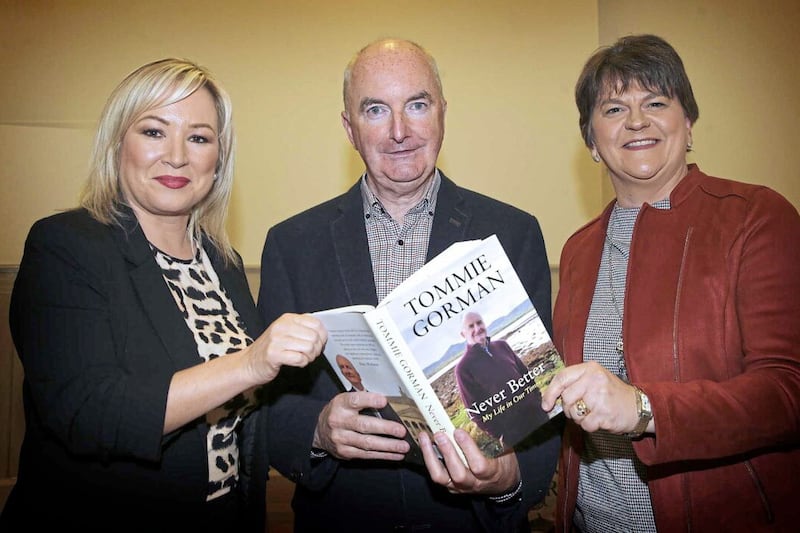

The likes of Ian Paisley, Peter Robinson and Arlene Foster were substantial figures. Nigel Dodds, born with no silver spoon, gained a first-class honours degree at Cambridge. His wife, Diane, once was a respected and able member of the European Parliament. As an agriculture minister, Edwin Poots’ pragmatism was noted, north and south. Gregory Campbell is probably the Northern Ireland politician who does the most forensic tracking of public service broadcasting.

At times, in challenging circumstances, DUP representatives went outside their comfort zone. Sammy Wilson attended the funeral of Brian Lenihan; Mervyn Storey developed a friendship with Éamon Ó Cuív. Peter Robinson showed his mellow side at his final North-South Ministerial Council, after Enda Kenny presented him with tickets for a Spurs-Arsenal match. Arlene Foster went to the requiem Mass of Martin McGuinness.

But in this current phase, the DUP seems content to embrace inconsequence. If Jeffrey Donaldson can’t persuade his party to re-engage, its drift towards the margins will continue. It’s difficult to see how staying on the sidelines could help the DUP in the next British general election. A Labour-led administration is unlikely to be more amenable that the Conservatives.

The DUP can assess how its stance affects Northern Ireland’s constitutional position and the debate about a border poll. But ultimately, politics is about getting things done.

In its preoccupation with itself, the DUP is flirting with irrelevance and creating a sense of drift in the society it is elected to serve. That stark assessment is made more in sadness than anger.