Twelfth of July celebrations in Northern Ireland traditionally begin with the lighting of bonfires the night before the biggest day of the marching season when members of the Orange Order take part in parades to commemorate the victory of the Protestant Dutchman King William of Orange over Catholic King James II at the 1690 Battle of the Boyne in the Republic of Ireland.

For many members of the Protestant, unionist and loyalist communities, the eleventh night is a time to join friends and neighbours and enjoy the spectacle, with neighbourhoods often hosting fun-days at bonfire sites in the hours leading up to midnight when the structures are put to the flame.

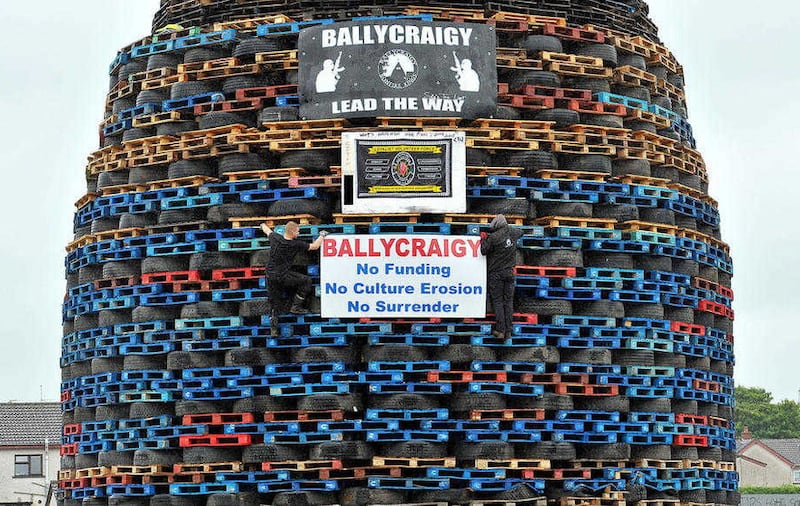

In recent decades, the bonfires have grown from street-by-street gatherings around smaller fires to events at huge pyres that tower over some loyalist areas in the weeks leading up to the 11th night.

Read more:

Beginnings of 11th night bonfires

Like all traditions associated with the Twelfth, bonfire night has its roots with King William of Orange.

It’s claimed that upon his arrival in Carrickfergus, Co Antrim, in 1690, ahead of the infamous Battle of the Boyne, bonfires were lit across Ulster in celebration of his landing by jubilant supporters.

Some even suggest the pyres were used to guide William and his troops as they sailed through Belfast Lough on their ships.

William’s victory over the Catholic James II is the basis of today’s Twelfth marches by the Orange Order and accompanying bands.

However, before the events of 1690, the lighting of bonfires was already a traditional Irish activity at times of celebration, dating back to the island’s pagan past, including during midsummer and at Samhain (Halloween).

Along with the eleventh night, the Irish bonfire tradition survives elsewhere, including on St John’s Eve in June, when many pyres light up the countryside across the south.

Do Catholics/nationalists/republicans have bonfires?

The Northern Ireland Catholic tradition of lighting bonfires to celebrate the Assumption of Mary in August was replaced during the Troubles with bonfires to mark the introduction of internment.

That practice has largely died out, and is now mostly confined to Derry’s Bogside area each year.

Building the pyres

Collections for eleventh night bonfires can often begin months beforehand, with collectors tasked with gathering wooden pallets, furniture and other items for burning.

In January 2017, piles of wood appeared at two sites of east Belfast bonfires six months before they would be torched.

Local councils oversee many bonfire management schemes, with funding dependent on issues including restrictions on what can be burned and when sites can be used to store materials for burning.

As July nears, teams of builders within communities begin stacking pallets over a period of weeks, forming the final bonfire structure.

Over the years, some communities have challenged themselves to break local and even international records for the height of the pyres. The Craigyhill bonfire 2022 in Larne measured 202 feet in height - higher than a 2019 bonfire in Lustenau, Switzerland that had been named the world’s tallest by Guinness World Records.

Dangers and controversy

Although a huge annual event for loyalist and unionist communities, the burning of bonfires is mired in annual controversy, due to what is burned within the pyres, and often what is displayed on them before they go up in flames.

In 2018, the Irish News published details from a leaked document commissioned by the Community Relations Council that exposed the extent to which some bonfires were controlled by loyalist paramilitary groups.

Groups including the UVF and UDA were using bonfires to “extend their legitimacy and control community activities”, it claimed.

Read more: Who are the UVF?

Today, flags and emblems relating to paramilitary organisations can often be seen at certain bonfire sites.

Meanwhile, each year controversy erupts over the burning on the bonfires of the tricolor which is the flag of Ireland, GAA emblems and other symbols of loyalists’ nationalist neighbours.

Often placed last-minute on the pyres to minimise criticism, election posters make frequent appearances on the pallet stacks, in what some within unionism claim is an act of protest, while critics see it as sectarianism.

Read more: 2023 bonfire builders hut decked in sectarian, violent and Nazi images

The building of bonfires at council-owned sites has led to stand-offs between builders and local authorities, such as Avoneil in east Belfast in 2019, while last summer saw tensions over a bonfire built close to an interface in the north of the city.

The spiralling height of many bonfires has also led to safety concerns. Last year saw the death of a bonfire builder in Larne after he fell over 50 feet from a structure.

The heat from the behemoth blazes can also keep the Northern Ireland Fire and Rescue Service busy on the 11th night as they douse nearby homes with water and foam to keep them cool.

Read more:Flats doused in foam at controversial Portadown bonfire

The burning of rubber tyres leads to pollution concerns, though in recent years efforts have been made to reduce the number of tyres torched.

Several areas have also made a switch to more environmentally friendly ‘beacons’ consisting of large cages filled with carbon-neutral willow wood.

Read more: Council removes 1,800 tyres from 2019 Belfast bonfire