A FORMER IRA prisoner who died earlier this year believed the treatment he received while being held in the H-Blocks led to the illness that claimed his life.

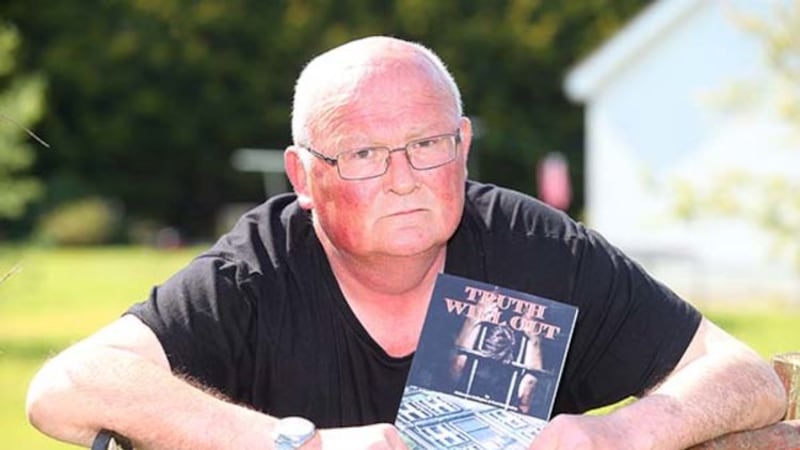

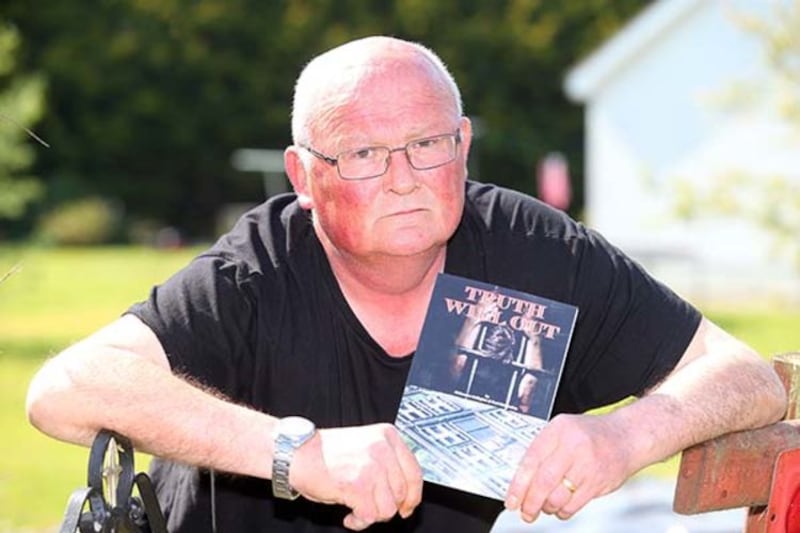

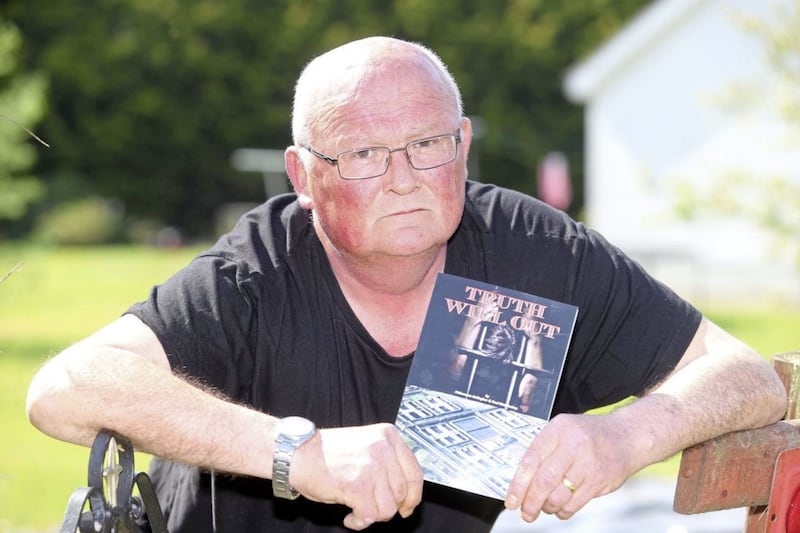

Speaking before his death in August, Paul McGlinchey repeated his view that chemicals used to clean cells during the 'no-wash protest' were responsible for his cancer.

Mr McGlinchey had requested that his interview would only be published after his death and with the consent of his family.

The 63-year-old suffered from a rare form of cancer which attacked his lungs, bones and spine.

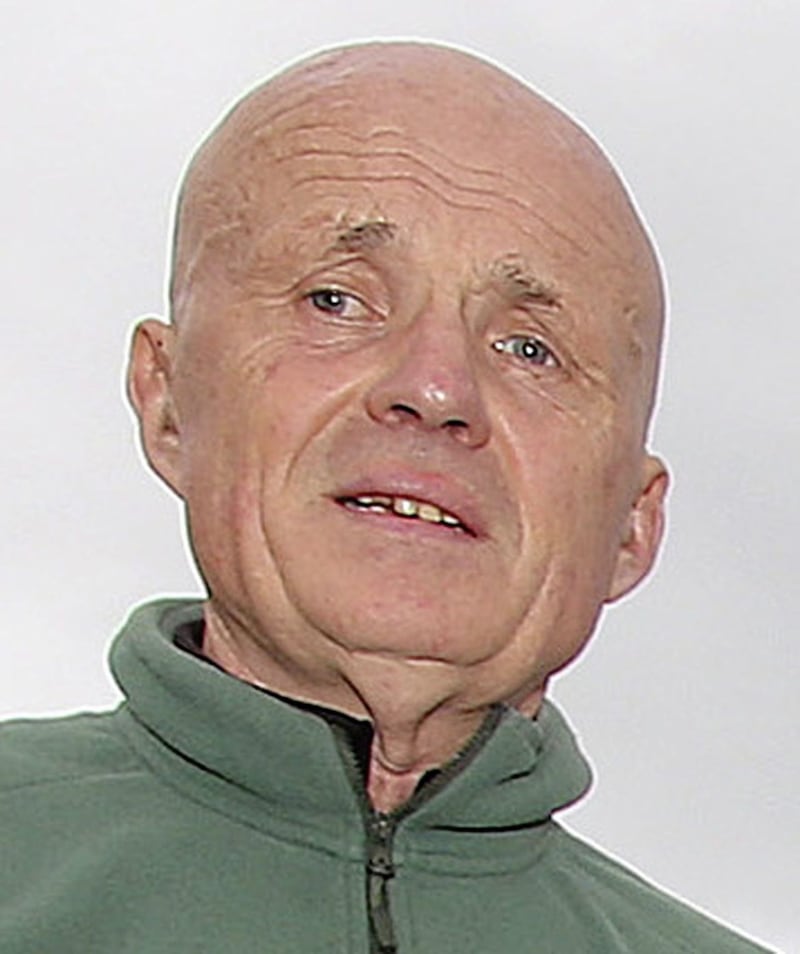

Originally from Bellaghy in south Derry, Mr McGlinchey was a brother of notorious INLA leader Dominic McGlinchey.

One time Ireland's most wanted man, he was linked to at least 30 murders and more than 200 attacks in Northern Ireland. He was assassinated in 1994 in Drogheda.

Another brother Séan is a Sinn Féin representative at Causeway Coast and Glens council.

The father-of-four was one of the first IRA prisoners to go 'on the blanket' after being sentenced for possession of arms as an 18-year-old in 1976.

He also served time in Portlaoise Prison for armed robbery in the 1990s.

The protest involved prisoners, dressed only in blankets, smearing their own excrement on cell walls as part of a campaign for political status.

The bitter dispute often spilled into violence and 20 prison offers were killed by republicans in the years between 1976 - 1981.

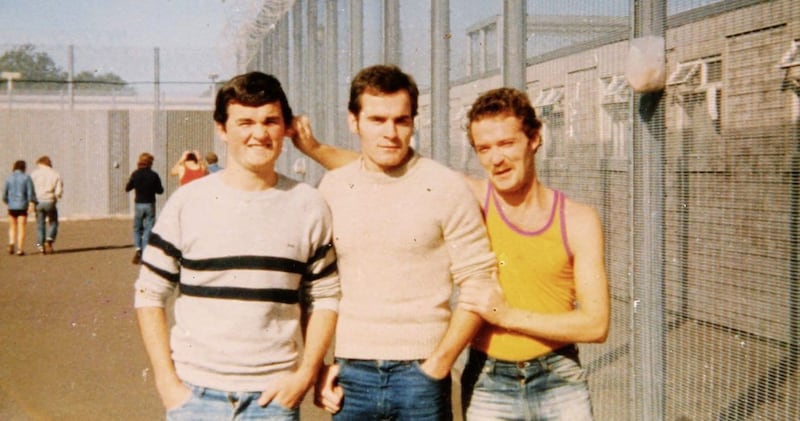

Mr McGlinchey is believed to have been the longest serving 'blanket man' and his 2017 book, 'Truth will Out', focused on his time in prison.

Speaking to The Irish News before his death Mr McGlinchey said only 0.1 percent of people contracted his type of cancer, which he described as "very aggressive".

"It started out as lymphoma and the way they explained it to me is it’s like a micro-chip programme to do one thing and in my case they start mutating and mating with each other and they do the same and each time they get more aggressive," he said.

He remained convinced his cancer was caused by the chemical agents used to clean cells during the years of protest.

"They opened the cell doors at night and just fired the stuff around us....we could not breathe, our eyes started to water and we had to smash the windows to get air," he claimed.

"They did that on a couple of occasions."

Mr McGlinchey believed that the use of chemicals in the prison was tactical.

"I always believed they had chemicals in our food and I think we were guinea pigs for the Brits to try out different chemicals and they were playing a long time war with us," he claimed.

"They were playing the bigger picture. They saw us as the future leaders and hard core when we got out of jail and this was their way of taking us out slowly.

"And a way of testing their chemicals."

Before his death Mr McGlinchey revealed that his medical team questioned him about his background.

"When I was in Belfast City Hospital seeing my consultant she asked me was I ever exposed to the military or the police and I told her I was in prison and had these chemicals thrown in the cells," he said.

"The following week when I was up I asked her had she treated any other prisoner from the blanket protest the same as myself.

"She said she had and that goes to prove in my eyes we were all exposed to the chemicals."

Mr McGlinchey said other former republican prisoners shared his view.

"I have spoken to other blanketmen and they are of the same opinion as me," he said.

"It was only then that blanketmen started to talk to each other and realised so many were having cancer and that’s where it came from."

While serving time on the blocks Mr McGlinchey and his fellow prisoners were subjected to full body searches.

He believes some of the attention he received during intrusive forced examinations amounted to "sexual abuse".

He added that he suffered from his injuries for days and that his complaints to a governor were dismissed.

Speaking before his death he said: "To call it a mirror search is the wrong term because what it was sexual abuse.

"Because our (private) parts were being searched and our back passage was being searched."

He remained bitter about his treatment and spoke of having "recurrent nightmares".

"A lot of men when they got out were not able to cope and some became suicidal," he said.

Mr McGlinchey viewed his fight against cancer as an extension of his republican beliefs.

"I still see it as part of the battle of the H Blocks, I am still fighting the Brits in my own mind," he said.

"My illness is a result of what they done to us during the blanket protest and I’m determined not to give in to them and fight it to the last breath.

"Only then will I get leaving the H-Blocks behind me."

He believes the prison protest, which culminated in the 1981 hunger strike, had a significant impact on Irish history.

"As a result of the sacrifice of the ten men the whole history and direction of the struggle changed," he said.

"A bit like after they executed the leaders of 1916 - nationalism became reawakened on the death of the hunger strikers."

In the years before his death Mr McGlinchey took part in a legal challenge over his treatment while in jail.

"It’s not just justice for us and our families," he said.

"If we could get a guilty verdict in the courts it will ensure that the Brits will never use it again or any other democratic government throughout the world."

He also hoped the courts would expose the abuse he claims he experienced.

"It would be exposed as blatant torture and sexual abuse and rape," he said.

"It may not be rape with a penis but it was rape using objects and fingers and iron bars."

As he faced his own mortality Mr McGlinchey talked about his devastation at missing out on seeing his children getting married and his grandchildren.

Despite this he maintained he had no regrets about his time as an active republican.

"I have no regrets about anything I done in the past," he said.

"No regrets about joining the IRA and going to jail and joining the protest and I’m proud of the protest.

"It was the only battle that the IRA won, we were fighting the Brits with our naked bodies.

"We took on the British empire with our naked bodies and we defeated them."

At his funeral in August Mr McGlinchey's coffin was draped in the 'Irish Republic' flag and a tricolour along with a black beret and gloves, while former 'blanket men' formed a guard of honour.

The Prison Service was contacted but made no comment.