British Government plans to ban future Troubles prosecutions risks undermining reconciliation in Northern Ireland, Labour has warned.

Shadow Northern Ireland Secretary Louise Haigh urged the British prime minister to think again on the contentious proposals as she met with families who were bereaved in shootings involving the British Army in west Belfast in 1971.

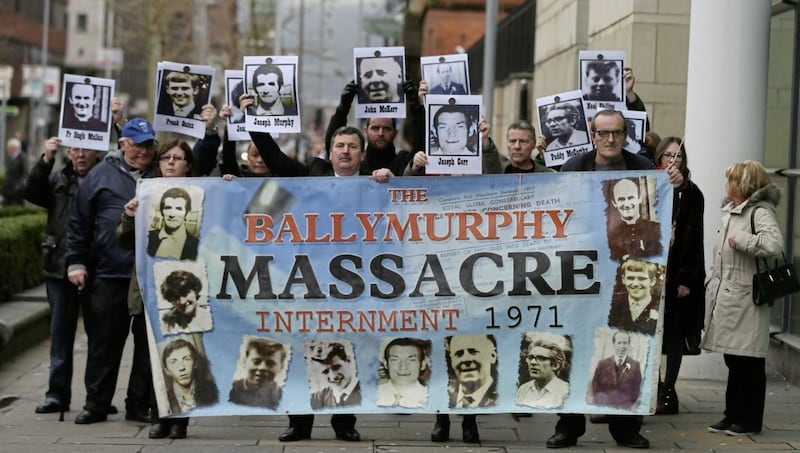

Today, Ms Haigh discussed the issue with relatives of some of the 10 people killed in the Ballymurphy shootings, which occurred 50 years ago this week.

Last month, Northern Ireland Secretary Brandon Lewis announced plans for a statute of limitations which would end all prosecutions for Troubles incidents up to April 1998 and would apply to military veterans as well as ex-paramilitaries.

The proposals, which Boris Johnson said would allow Northern Ireland to “draw a line under the Troubles”, would also end all legacy inquests and civil actions related to the conflict.

But the plan has been heavily criticised by all the main political parties in Northern Ireland, as well as the Irish Government and a range of victims and survivors groups.

Earlier this year, a long-running inquest into the Ballymurphy shootings reached conclusion when a coroner declared all 10 victims were “entirely innocent” and found the Army was responsible for nine of the deaths.

Ms Haigh said: “I’ve met victims from across the community here in Northern Ireland and over in Great Britain and so far the message has been absolutely unanimous – they are opposed to the Government’s offensive proposals on amnesty.

“We need to see a change of heart and a proposal that’s committed to the rule of law and finding truth and justice for victims across the picture.

“I think if Boris Johnson and the Secretary of State actually came here to talk to victims and survivors themselves, they would see there is no support from victims, from political parties, and that there is genuine fear that these proposals are going to set back reconciliation and the promise of the shared future that the Good Friday Agreement made.

“If they come and actually have these conversations themselves, I’m hopeful that they will have a change of heart and revert back to the kind of proposals that we saw in the Stormont House Agreement.”

The 2014 Stormont House Agreement struck between the UK and Irish governments and the main parties in Northern Ireland involved a range of mechanisms to deal with the toxic legacy of the conflict, including a new independent investigations unit.

Ms Haigh added: “I think everyone accepts that prosecutions are going to be only likely in a handful of cases, but to shut down the chance of prosecution where there is new compelling evidence, where there are new techniques… would be completely in contravention to the rule of law and, crucially, the human rights that are the basis of the Good Friday Agreement and we cannot be ripping them up at this crucial moment in Northern Ireland’s history.”

John Teggart, whose father Danny was killed in the Ballymurphy shootings, welcomed Ms Haigh’s visit.

He vowed to fight the statute of limitations proposals.

“We’ll put up a fight, we’ll put up a good fight,” he said.

Mr Teggart said the vindication that the Ballymurphy families had secured through the inquest process should not be denied to other relatives.

“A lot of families coming behind us have got hope from what we did and that’s why we need to be taking this off the table, not just for ourselves, but for others coming behind us,” he said.