"WE are beyond the beginning, but we are not yet in sight of the end."

The words of British prime minister John Major following the announcement of the 1994 IRA ceasefire proved prophetic, as there would be a few bumps on the road before Northern Ireland reached a lasting, if uneasy, peace.

In the first eight months of 1994, 118 had people died in at the hands of paramilitaries, including three RUC officers, six Catholics gunned down watching a World Cup game in Loughinisland and former INLA leader Dominic McGlinchey in Drogheda.

But behind the newspaper headlines momentum was building towards a cessation of violence.

Leading republican Sean 'Spike' Murray would later talk of the years leading up to 1994 as "a situation of military stalemate".

"We weren't strong enough to defeat the British war machine and the British war machine wasn't strong enough to defeat republicanism," he told The Irish News afterwards.

"There was a sense that things were moving and moving in a particular direction, though not everyone would've been aware of what the specifics were.

"Republicans aren't sheep - they need to be convinced before they can make a transition."

Then Sinn Féin president Gerry Adams yesterday described August 1994 as "an intense month".

"To be honest, neither Martin (McGuinness) nor I really knew if we would succeed," he said.

"We were attempting something unique and exceptional - to construct a series of agreements which together could persuade the IRA leadership that there existed an alternative to armed actions capable of achieving republican goals.

"The danger was that if we pulled everything together and the army said `No' then the process was over before it really started."

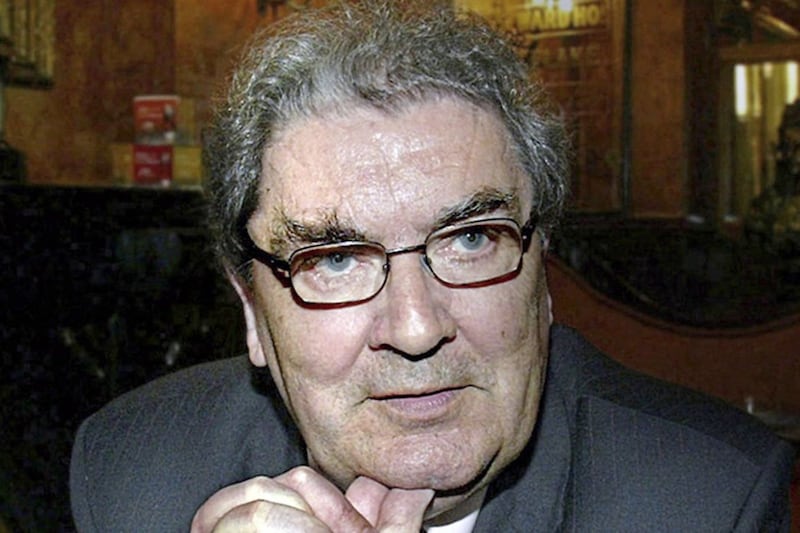

Sinn Féin was talking to SDLP leader John Hume, and via the Irish American Connolly House group lobbying the Clinton administration to develop "a new Irish agenda".

Mr Adams said at a briefing in early August with the IRA leadership, Martin McGuinness "was able to tell it that the Irish government had provided written assurances that if there was a cessation there would be an immediate response on practical matters. Sinn Féin would be treated like any other political party".

"The IRA leadership listened attentively to what we had to say. It agreed to meet again to receive an update from us. It was coming close to make your mind up time. Everyone at the meeting knew this. Some of the leadership were against a cessation. They had been very frank about that. It was going to be a close call."

There followed choreographed "public initiatives" from Mr Hume, Taoiseach Albert Reynolds and the Connolly House group which signalled "the coming together of the different pieces of the jigsaw".

A key piece of that was "a visa for Joe Cahill", which Mr Adams said was "a test to see if the Irish government was prepared to take on the British and if it could win such a political battle with the British within the US administration".

"It would also be an important indicator of how seriously the Clinton administration intended to take the issue of peace in Ireland."

A joint statement from Mr Hume and Mr Adams was followed within hours by one from the taoiseach expressing a belief that a historic opportunity was opening up.

"Martin and I met the army council again," Mr Adams said.

"The meeting was inconclusive. People needed more time to consider all the issues. Joe's visa became an even greater test. Then late on Monday night, August 29, President Clinton cleared Joe's visa.

"Martin and I again travelled to meet the army council. A package had been agreed. It was now over to the IRA leadership. Everyone at the army meeting was a little tense. Martin McGuinness spoke eloquently. So did others. For and against."

He said one of his late colleague's "great qualities was his sense of conviction and confidence" and ability to "bring a strength to a debate which was very, very compelling".

"You knew he was going to deliver on any commitment he made or die trying. The struggle wasn’t ending, we told them. They knew that of course."

He said "the easy decision was for the IRA to continue to fight", while "the high-risk option was the one we were arguing for".

"It meant uncharted waters. It would involve compromises. It could mean risking - and losing - everything. But we could also be the generation who would win freedom. We could set in place a process which could create new conditions for a genuine and just peace and from there build a pathway and a strategy into a new all Ireland republic."

He said the vote for a cessation "was not unanimous but those who voted against pledged their support to the new position".

The ceasefire statement from `P O'Neill' was delivered to security reporters Eamonn Mallie and Brian Rowan in Belfast and Charlie Bird of RTÉ in Dublin on the morrning of August 31 1994.

It read:

"Recognising the potential of the current situation and in order to enhance the democratic process and underlying our definitive commitment to its success, the leadership of the IRA have decided that as of midnight, August 31, there will be a complete cessation of military operations. All our units have been instructed accordingly.

"At this crossroads the leadership of the IRA salutes and commends our volunteers, other activists, our supporters and the political prisoners who have sustained the struggle against all odds for the past 25 years. Your courage, determination and sacrifice have demonstrated that the freedom and the desire for peace based on a just and lasting settlement cannot be crushed. We remember all those who have died for Irish freedom and we reiterate our commitment to our republican objectives. Our struggle has seen many gains and advances made by nationalists and for the democratic position.

"We believe that an opportunity to secure a just and lasting settlement has been created. We are therefore entering into a new situation in a spirit of determination and confidence, determined that the injustices which created this conflict will be removed and confident in the strength and justice of our struggle to achieve this.

"We note that the Downing Street Declaration is not a solution, nor was it presented as such by its authors. A solution will only be found as a result of inclusive negotiations. Others, not the least the British government have a duty to face up to their responsibilities. It is our desire to significantly contribute to the creation of a climate which will encourage this. We urge everyone to approach this new situation with energy, determination and patience."

According to Mr Murray's later account: "At the time I don't think anyone thought the ceasefire was permanent.

"It was more a case of let's see what the response is like by way of demilitarisation and the quick convening of all-party talks."

While the response from the Dublin administration was warm, with foreign minister Dick Spring describing the statement as "historic" and meeting his government's demand for an unconditional end to IRA violence, London's reaction was cautious in the face of unionist suspicion.

Albert Reynolds called on loyalist paramilitaries to follow suit, but there was deep unease among that community which was suspicious of a `sell out' by Britain.

UUP leader James Molyneaux insisted no moves towards talks should begin until the IRA had added the word `permanent' to the ceasefire declaration.

He was quoted as saying that "a prolonged IRA ceasefire could be the most destabilising thing to happen to unionism since partition".

Meanwhile, DUP leader Ian Paisley said the statement was an "insult to the people [the IRA] has slaughtered because there was no expression of regret".

The announcement came 18 months after secret talks began between the British government and republicans and followed a joint April 1993 statement from John Hume and Gerry Adams which accepted that unionists should be taken into account in any political settlement, but they must also accept a principle of Irish self-determination.

Hume had initiated a series of private discussions with Adams in 1988, but it was not until that 1993 statement that the shift was made towards political negotiation.

December had seen the resulting Downing Street Declaration by Major and Reynolds, affirming the right of self determination and that Northern Ireland would be transferred to the Republic from the UK only if a majority of its population was in favour.

It also included the `Irish dimension' principle of consent - that the people of the island had the exclusive right to solve the issues between north and south by mutual consent.

Six weeks after the IRA ceasefire, Gusty Spence, founding member of the UVF, made a statement on behalf of the Combined Loyalist Military Command declaring loyalists would end their violence at midnight and offering "true and abject remorse" to the families of all innocent victims of the Troubles.

However, unionist and loyalist unease at what form a final settlement with republicans might take saw momentum slow to a pace which ultimately proved unacceptable to the IRA.

"They (the British government) had this concept of a decontamination period and there were no signs of demilitarisation, which eventually led to the breakdown in 1996," Mr Murray would later claim.

It was not until the election of a Labour government the following year that a fresh impetus was injected into the process that would ultimately lead to a second ceasefire and the Good Friday Agreement.