A judge who ruled that a damning report into the Loughinisland atrocity was unlawful is to step aside from the case - despite rejecting claims he could have been seen as subconsciously biased.

Amid unprecedented courtroom developments, Mr Justice McCloskey held the challenge to Police Ombudsman findings that RUC officers colluded with loyalists who killed six Catholic men should be re-run in front of another member of the judiciary to ensure victims' relatives confidence in the final outcome.

He said: "Our legal system will not have served the families well if they are not given the opportunity of having this case heard by a differently constituted court."

The outcome meant no final order could be made on whether to quash the watchdog report under challenge.

But before reaching his determination the judge also set out his view that parts of the Ombudman's report could have been removed, leaving the rest of it intact.

Last month he had delivered a landmark verdict that the Ombudsman's conclusions were procedurally unfair.

In High Court litigation mounted by two retired senior policemen, he found it had gone beyond the body's statutory powers in reaching conclusions on events surrounding the massacre which were unsustainable in law.

UVF gunmen opened fire in the Co Down village pub as their victims watched a World Cup football match in June 1994.

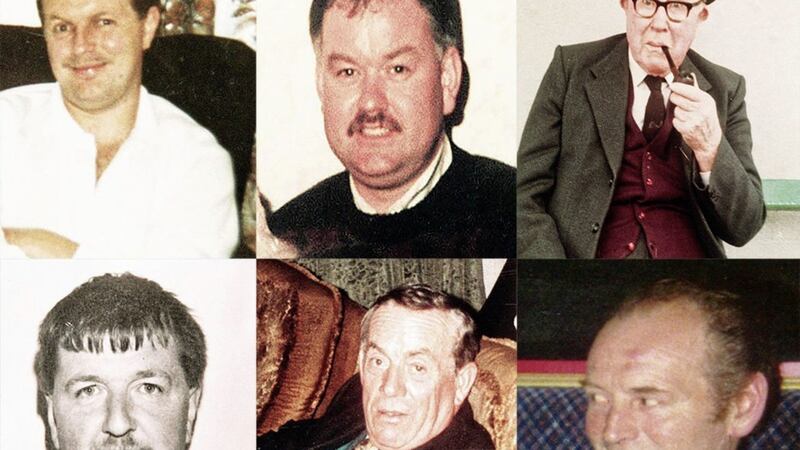

Six men were killed: Adrian Rogan, 34, Malcolm Jenkinson, 53, Barney Green, 87, Daniel McCreanor 59, Patrick O'Hare, 35, and Eamon Byrne, 39. Five others were wounded in the attack.

In June 2016 the Police Ombudsman, Dr Michael Maguire, said collusion between some officers and the loyalists was a significant feature in the murders.

He found no evidence police had prior knowledge, but identified "catastrophic failings" in the investigation.

One of those who issued judicial review proceedings against Dr Maguire's assessment was Raymond White, a representative of the Northern Ireland Retired Police Officers' Association.

It was stressed that the report had not blamed him for any of the alleged investigative failings.

Following the main ruling lawyers representing the Ombudsman and relatives of those killed in the massacre argued that Mr Justice McCloskey should withdraw due to a potential perception of subconscious bias.

Their application was based on his role as a barrister in a separate legal challenge 16 years ago.

The court heard he was involved in a separate legal bid in 2002 to overturn former Police Ombudsman Nuala O'Loan's devastating report into the Omagh bomb investigations.

Mr Justice McCloskey had acted as senior counsel for police officers behind that challenge - who included Mr White.

Newly instructed counsel for the Ombudsman, Barra McGrory QC, and the Loughinisland families' legal representatives argued that he should recuse himself to enable a fresh hearing before another judge.

During the legal move counsel emphasised they were not calling into question his judicial independence or integrity - instead basing their application on possible public perception.

Mr Justice McCloskey confirmed he had no memory of being involved in the earlier litigation until it was drawn to his attention, describing his recollection as "zero".

Returning yesterday to deliver his final judgment, he refused the application after describing submissions advanced on behalf of the Ombudsman as "flimsy, artificial and entirely unpersuasive".

Determining that the watchdog could have made the legal request last month, he described suggestions that insufficient information was available at that stage as "manifestly unsustainable".

Based on all available information and affidavits, he concluded that the test for recusal was not satisfied.

"In my judgment, the independent observer would not reasonably apprehend a realistic possibility of subconscious bias in this court's resolution of certain pure questions of law in favour of the applicants."

Despite that assessment, he went on to set out his reasons for deciding a fresh hearing before a different judge should now take place.

"To describe the events which have materialised in the aftermath of this judgment as unpredictable and unprecedented is to indulge in understatement," he said.

"The families have been engulfed in a veritable maelstrom."

Relatives of the Loughinisland victims have found themselves repeatedly travelling to and from the High Court, trying to absorb a concoction of evolving legal advice, submissions, new evidence, a change of counsel, repeated adjournments and intense public and media attention, he pointed out.

Mr Justice McCloskey continued: "I would expect that they have found their six year encounter with our legal system bewildering and confusing."

He added: I consider that, in the truly unique and unprecedented circumstances of this case, the interests of justice will not be furthered by a formal and final outcome which gives effect to the court's substantive judgment and choice of remedy."

Mr McGrory, a former Director of Public Prosecutions, had applied to have the judge step aside after replacing senior counsel previously instructed by the Ombudsman.

He argued that reassurances about no unconscious bias which could have been given at the outset of proceedings couldn't be given now a ruling has been made in favour of the policemen.

With the potential for an appeal against findings reached on the Loughinisland report, the Ombudsman's lawyers had to seek recusal if they plan to raise that point at any future hearing.

Mr Justice McCloskey stressed his involvement in thousands of cases over the course of a 38-year career in private practice and on the bench.

Stressing how Mr White was not a party in the 2002 litigation, he also detailed five stages at which the issue was considered and the view taken that recusal action was not appropriate.

The Ombudsman would have been advised before and immediately after the original hearing that there were no grounds for such an application, the judge said.

"To summarise, I find the evidence and argument put forward on behalf of the Ombudsman pertaining to the aforementioned issue flimsy, artificial and entirely unpersuasive."

Declining to draw up a final order on remedies because of his evaluation, Mr Justice McCloskey instead confirmed: "There will be a fresh hearing before a differently constituted court."

His verdict on the merits of the challenge will have no binding impact on those proceedings.

He explained: "It will, rather, assume a hybrid status, somewhat akin to that of an advisory opinion, which features in legal systems other than ours."