A FORMER Tyrone GAA star has won his appeal against the minimum 10-year jail sentence imposed for shooting dead his father.

Senior judges ruled that Sean Hackett should instead serve seven years before he can be considered for release on licence.

Backing fresh medical evidence that the 21-year-old is suffering from a delusional disorder, they held that his culpability for killing Aloysius Hackett was not as high as suggested at trial.

Although the Court of Appeal resisted defence arguments for a hospital order, Lord Chief Justice Sir Declan Morgan said the Department of Justice should also urgently consider making a prison transfer to ensure Sean Hackett is treated for his condition.

Hackett was challenging the life sentence with a minimum 10-year tariff imposed for the manslaughter of his father Aloysius at the family home near Augher, Co Tyrone in January 2013.

A jury found him guilty last year on the grounds of diminished responsibility after acquitting him of murder.

Aloysius Hackett, a former chairman of St Macartan's GAC in Augher, was shot twice in the head on the driveway of his Aghindarrah Road home.

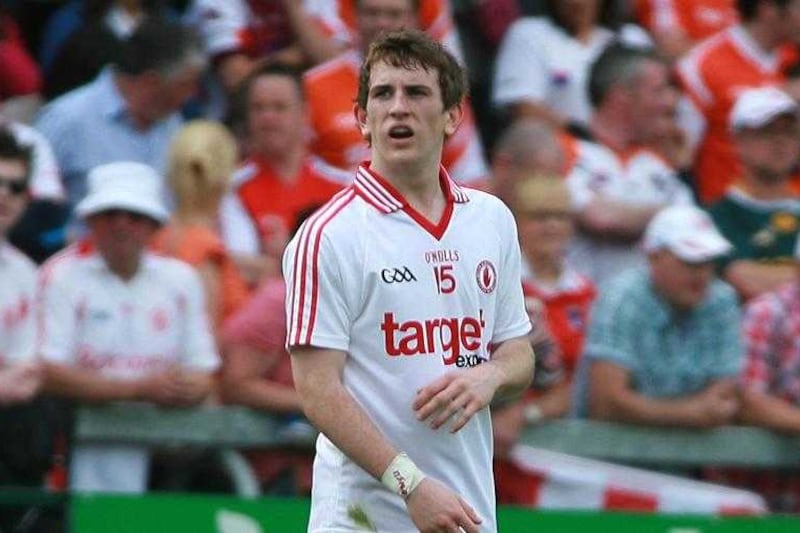

His son Sean, who previously captained the Tyrone Minor GAA team, admitted carrying out the shooting but consistently denied murder.

At his trial it was set out how he had suffered depression in the preceding months, triggered by a split from his girlfriend.

Appealing the sentence imposed, his legal team submitted that he comply with a hospital order if the court considered it an appropriate alternative.

Up to five psychiatrists backed the view that Hackett was in a delusional state of mind when he carried out the killing at the age of 18.

One of those experts called to give fresh evidence was Dr Carine Minne, who is based at the high security Broadmoor Hospital in Berkshire.

She told the court Hackett had been harbouring a secret need to kill either of his parents.

According to Dr Minne he is suffering from one of the purest forms of delusional disorder she has ever encountered - with no other case like it in Northern Ireland.

Sir Declan, who heard the appeal with Lord Justices Girvan and Coghlin, was told Hackett remains both a suicide and homicide risk while he remains untreated.

A series of factors contributing to Hackett's mental health deteriorating in the months leading up to the shooting were identified.

As well as breaking up with a girlfriend, the psychiatrist pointed to the death of a grandparent and the blow to his self-esteem when he failed to be picked for a football team.

By Autumn 2012 he had developed a belief that killing either of his parents would solve his problems, she claimed.

Hackett first lured his mother into the family garage in a bid to strangle her, only to come to his senses and stop when she struggled and screamed.

Following that incident Hackett was taken to his GP and attended one counselling session.

However, his continued plan to kill one or other of his parents remained secret.

Hours before the shooting he nearly killed his mother, but was said to have stopped at the last minute because he could not bring himself to carry it out.

However hours later he did shoot his father. Armed with a rifle, he waited for the victim to return home from a GAA meeting.

Crouching behind a car, Hackett felt powerful and excited by what he was about to do, the court was told.

He fired three shots. His father did not die instantly. The blood trail established that he moved 26ft after the first shot was fired.

In Hackett's delusional state, Dr Minne claimed, he felt he had to fire again to ensure the victim was dead.

Immediately after pulling the trigger he stood over his father in a calm state of disbelief, unsure whether it was a dream or reality.

Following the killing he walked around the house and returned to scene, apparently to check what had happened was real.

Hackett confessed to police after first lying by claiming to have found his father's body and suggesting there had been a burglary.

His mother Eilish was in court, accompanied by other members of the family, to hear the appeal outcome.

Hackett listened via prison video-link as the judges concluded, on the balance of probabilities, that he had been suffering from a delusional disorder at the time and continues to do so.

Differing from the trial assessment of Hackett's overall responsibility as being comparatively high, Sir Declan said: "We conclude that the appellant's culpability was low but not minimal and that punishment is not inappropriate."

He pointed to the need for prolonged psychotherapy within a secure hospital environment, with the Shannon Clinic being the only available option in Northern Ireland.

Without such treatment Hackett will either remain detained indefinitely because he poses a risk of serious harm, or alternatively he will be released in circumstances where he actually constitutes such a threat, the judge pointed out.

He said the evidence suggests the risk could be managed in the community within a period of 10 years.

Sir Declan confirmed the court has no power to direct a prison transfer order.

But stressing the requirement for Hackett to be treated in either the Shannon Clinic or another suitable location, he added: "That compelling need reflects the public interest in dealing with a dangerous offender as well as the appellant's personal needs.

"In those circumstances we have concluded that we should not impose a hospital order, but that this case requires the Department to urgently consider the making of a prison transfer order."

The judge continued: "This was a truly shocking offence, but the medical evidence that we have accepted shed considerable light upon the circumstances."

Despite deciding Hackett's responsibility was at a lower level, Sir Declan confirmed that culpability was still "more than minimal".

Allowing the appeal, he substituted the minimum 10-year sentence originally imposed for a new term of seven years before the defendant can be considered for release.