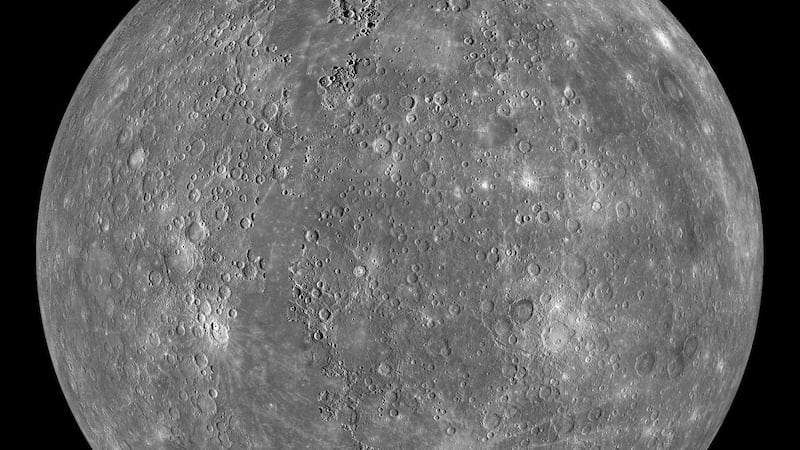

New research strongly suggests that the planet Mercury is continuing to shrink.

The smallest planet in the solar system began to contract at least three billion years ago, and experts suggest it is likely that the rate of contraction has been decreasing since then.

Mercury’s radius may have decreased by as much as 7km, models and observations indicate.

The contracting of the planet has produced lobate scarps, which are long, tectonic structures on its surface.

But until now, evidence of tectonic activity on Mercury has been lacking.

While undertaking a global survey of Mercury using data from Nasa’s Messenger mission (2011-2015), Open University (OU) research student Benjamin Man, who led the study, discovered small, fresh landforms called grabens.

Mr Man said: “The discovery of small grabens associated with larger tectonic structures was serendipitous.

“As part of my doctoral studies, I have made the first geological map of a region of the planet and whilst doing so, I came across some of the most impressive examples of these.

“This led me to undertake a global survey where I looked at over 25,000 individual images where I discovered hundreds of small grabens.

“Our discovery of so many grabens is significant as it indicates that not only has Mercury’s tectonism been active recently, but it is also widespread across the surface of the planet.

“This is important as it confirms that global contraction is ongoing and raises questions regarding the thermochemical properties of Mercury’s interior.”

The grabens are small, shallow landforms, and so they would not be expected to survive for hundreds of millions of years, let alone a billion years.

The researchers measured the depths of the grabens by looking at the length of the shadows they cast and calculating the position of the spacecraft and the position of the sun.

They also predicted the maximum depth of the structures when they first formed using the length of the structures.

The researchers then calculated how long it would take for them to infill and consequently found that many of the grabens likely formed in the past few hundred million years.

The discovery of so many of these features on many large compressional tectonic structures shows that recent tectonism – the faulting or folding of the outer layer of a planet – is widespread on Mercury.

Researchers suggest the study, published in Nature Geoscience, provides strong evidence for continued global contraction into the present day.

David Rothery, professor of planetary geosciences at the Open University, is the lead supervisor of the project and a member of the science team for BepiColombo.

He said: “As well as finding many clear examples of small grabens atop lobate scarps, Ben found an even greater number of likely examples that we can’t be sure of, because the detail in the Messenger images is not quite clear enough.

“When the joint European/Japanese mission BepiColombo starts to send back even more detailed pictures from orbit about Mercury early in 2026 these ‘probable’ grabens will be among its targets, which will enable the scale and extent of recent fault movements on Mercury to be clarified – or possibly refuted if Ben and I are wrong. That’s how science works.”