FAMOUS personalities are often asked by the media how they spend Sunday or whether religion affects their lives.

There has always been interest in how faith, or lack of it, impacts the way we live.

The religious beliefs of renowned microbiologist Louis Pasteur were fundamental to his life.

Born in France in 1822 to a poor Catholic family, in his early years he was an average student.

Over time he developed an interest in science, where his deft laboratory skills and critical mind led him to numerous ground-breaking discoveries which helped found the field of microbiology.

He is best known for inventing the technique of treating milk and wine to stop bacterial contamination, a process now called pasteurisation.

He also was a pioneer in vaccine development, creating the first vaccines for rabies and anthrax which saved the lives of many.

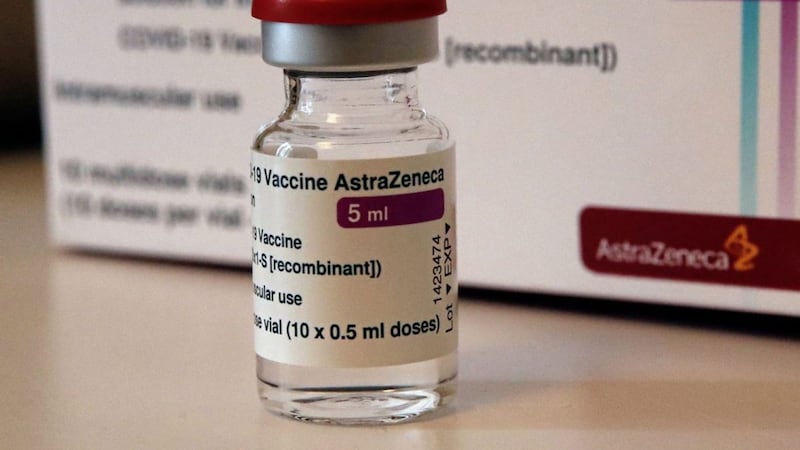

Our ability to create effective vaccines against Covid-19 and so preserve life owes a great deal to the work of this holy man who once remarked: "A little science takes you away from God but more of it takes you towards Him."

In recent times society has lost sight of the divine, thereby greatly limiting science's ability to truly advance the common good.

Could it ever be wrong to cause the natural birth of a child? Herbert Chessin, an American obstetrician, was sued on exactly these grounds.

In 1969 he was asked for medical advice by Hetty Park, who had recently given birth to a daughter who died of kidney disease hours after birth.

She was eager to know whether the disease was genetic, and Chessin informed her it was not.

In 1970 the Parks conceived again and gave birth to a daughter, Laura, who also had kidney disease and died aged two-and-a-half.

The Parks took Chessin to court, claiming that their daughter had been a victim of a flawed decision.

Our ability to create effective vaccines against Covid-19 and so preserve life owes a great deal to the work of Louis Pasteur, a holy man who once remarked that, 'A little science takes you away from God but more of it takes you towards Him'

In such cases, the defendant usually stands accused of the wrongful causation of death, but the Parks argued that Chessin was guilty of "the wrongful causation of life".

In a landmark judgment, the court agreed with the Parks. "Potential parents have a right to choose not to have a child when it can be reasonably established that the child would be deformed," the judge remarked.

Are we to assume that the life of Laura was worthless? Cases like this one mark a departure from the Christian stance that all human lives merit protection; the result is confusion and distrust.

Nowadays people are questioning developments in transgender medicine, where medical decisions may be made with insufficient information.

Any form of wisdom derived from a divine plan is scorned, but hasty decisions are often regretted, as the British Medical Association has noted.

Keira Bell was uncertain of her gender and underwent life-changing medical procedures when she was just 16, taking drugs to delay puberty and having her breasts removed.

Left sterile, Bell changed her mind and challenged the Tavistock Clinic where she underwent medical surgery.

The court decided in her favour, ruling that it was highly unlikely that someone aged 16 could give informed consent to taking puberty blockers.

"The first duty of medicine is 'Do no harm'," said a Canadian paediatrician recently in The Economist.

"In any other branch of medicine if you were causing permanent sterility with body-altering surgery, you had better have some pretty strong information... But we're already going down that road with no strong information at all."

The Biden administration has passed new transgender laws. In turn, some States have passed laws in opposition and President Biden has been accused of attacking women's rights. It is a confusing picture.

Scientific progress is often thought to derive from 'eureka' moments, but in reality is mainly made in incremental steps, aided by careful attention to the observations of others.

Pasteur recognised this when he remarked: "In the field of observation, chance favours only the prepared mind."

This compassionate and hard-working man died while having the life of St Vincent de Paul read to him, hoping that his work, like St Vincent's, would save suffering children.

May we pray for more scientists like Pasteur, gifted with the patience and compassion at the heart of the Christian faith.

Dr Brian Wilson grew up in Ballymena, Co Antrim, completed undergraduate studies in Chemistry at Imperial College London and holds a PhD in Organic Chemistry from the University of Oxford.