THEY say truth is stranger than fiction, but the globe-trotting life-story of journalist and die-hard physical force Irish republican John Mitchel is simply extraordinary – as readers of Anthony G Russell's new biography Between Two Flags will discover.

Born in Camnish, Co Derry – a county in which at least two GAA clubs today bear his name – on November 3 1815, John Mitchel moved to Newry at age eight. His father, the Rev John Mitchel, was a progressive Presbyterian minister known for his independence of thought and conciliatory manner. However, John junior's character would quickly become defined by his extreme opinions and lack of compromise.

In 1848 the Trinity College-educated, Young Ireland-affiliated Mitchel was was arrested in Dublin for preaching sedition via his publication, The United Irishman. Along with his fiercely loyal young wife, Jenny Verner – who he had eloped with and married at Drumcree in 1837 – Mitchel subsequently escaped while serving a 14-year sentence in an Australian penal colony, smuggling his young family to the United States.

The Irishman's stubbornly entrenched political and racial ideas were expressed through the publications he founded and wrote for in the US, often confounding even his closest friends and providing ample ammunition for enemies to use against him.

As the American Civil War rumbled to life in the 1860s, the Mitchel clan sided with the Confederate rebels. Mitchel himself served in the Confederate Army's Ambulance Corps, while all three of his sons served with distinction in the Confederate forces: John and Willie were both killed in battle, while James was maimed.

Twice elected as MP for Tipperary just before his sudden death in 1875, Mitchel's strident, Famine-inspired republican writings in his prison-penned Jail Journal and passionate belief that Irishmen of all religions should unite against British rule under the Irish tricolour would later inspire Patrick Pearse in 1916.

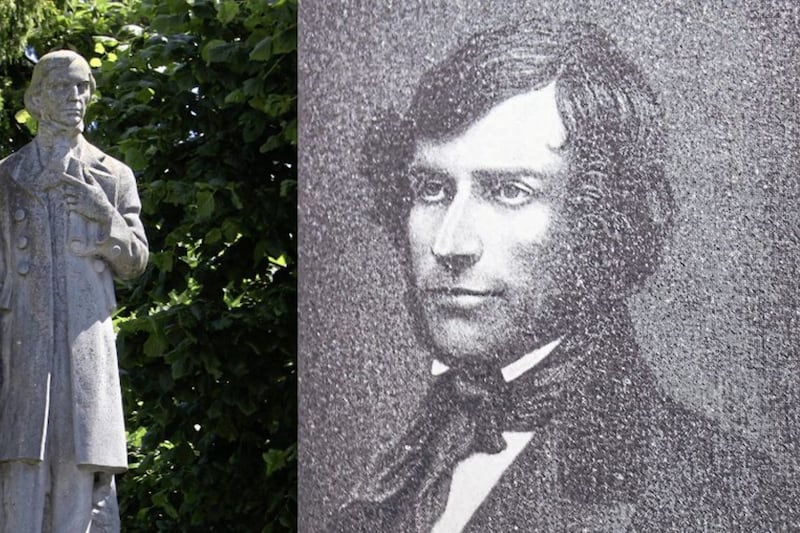

While a statue honouring Mitchel as an 'exile for the sake of Ireland' still stands in Newry today, his Confederate affiliation and unshakable belief that slavery was "the best state of existence for the negro" now taints his legacy.

Ironically of course, this fatal flaw in John Mitchel's character also makes his life story all the more fascinating.

"From a modern perspective, it's very hard to come to terms with his beliefs," agrees Anthony G Russell. "But certainly he does deserve to be reassessed, because he is the forgotten hero of 1916. He was very influential as far as Pearse was concerned – he called him 'the last of the four gospels of the new testament of Irish nationalism, the last and the fieriest and the most sublime'.

"The Irish tricolour is his flag."

The Newry-born historical geographer, who has written and produced major exhibitions on the 1798 Rebellion, the Famine and the Young Ireland movement in which John Mitchel was so active, admits to a life-long interest in this controversial republican figure.

"The book is titled Between Two Flags, but actually its genesis was between two houses," explains Russell, who recently retired from Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge.

"I was reared beside Jenny Verner's house. I would have played in their garden and my father told me the story of the elopement. Then, in my 20s, we moved to Dromalane about 20 to 30 yards from where John Mitchel died.

"Although my professional career took me in various directions, that story was always in my mind. So when I retired about two and a half years ago, I decided to write it."

In addition to researching and writing what is surely now the definitive account of John and Jenny's eventful life together – throughout which the latter braved jungles, shipwrecks and the death of several children to remain with her partner – Russell also helped take what he has described as "a real life love story more adventurous and romantic than The Quiet Man, Ryan’s Daughter, Titanic and Gone With The Wind" to the stage.

"About six years ago, we began a project here in Newry called Rebels and Loyalists," he tells me. "We took the story of John Mitchel and Jenny Verner and built an exhibition and musical around it."

Indeed, the descriptively titled The Musical Love Story of John Mitchel and Jenny Verner featuring pianist Gerry Doherty has been performed in churches across the north with great success.

"We've been all over Ulster with it," enthuses Russell. "Despite the fact that John Mitchel was a physical-force republican, the romance of their story wins through. Jenny supported him totally – they had an absolutely wonderful relationship."

Still, there's no getting away from the almost comical irony of Mitchel continually defending black slavery (despite never owning slaves himself) while demanding Irish freedom. Russell attributes such stubbornness to Mitchel's conveniently narrow, middle class view of the world.

"He gave a speech to the University of Virginia in 1854 where he started off by saying 'there is no progress'," the author explains.

"Now, Mitchel accepted technological change – he had to, he wasn't a stupid man – but he firmly believed that mankind had not truly progressed since classical times, particularly the Roman Republic. And he would not deviate from that.

"Most tragically of all, as his beloved Confederacy was being finished off by Ulysses S Grant, the Confederate Congress wanted to put black slaves into the army, which Mitchel couldn't accept. With no trace of irony at all, he wrote that 'if what we have done to the black man isn't true, then it a terrible black stain on the white race.'

"Yet, in other ways, John was a very liberal man and so was Jenny. For example, when their daughter Henrietta converted to Catholicism and joined a convent, they had no problem with that at all. In fact, Mitchel scolded his mother for being quite reactionary about it."

The thorny issue of the Irishman's allegiance to 'the wrong side of history' even reared its head when it came to designing the artwork for Between Two Flags.

"One of the discussions I had with the publisher was about whether we should put the Confederate battle flag on the book at all," reveals Russell, who in the end decided to include both it and the Irish tricolour on the back cover.

"Given what's happening at the moment in America regarding the removal of that flag from public buildings in the American south, I'm not sure whether it will be good for sales or not."

As for what should be done to mark the imminent 200th anniversary of John Mitchel's birth, it seems no agreement has yet been reached by interested parties on how to deal with this divisive historical figure.

"The National Famine Commemoration Conference is coming to Newry on September 26," comments Russell, who is the director of the event.

"Our theme is 'John Mitchel and the legacy of the Irish Famine', but oddly enough there was certain opposition to having Mitchel's name associated with it.

"He's still considered too controversial."

:: Between Two Flags is available now published by Merrion Press and will be launched by the author in Belfast at The Linen Hall Library on August 26. The Musical Love Story of John Mitchel and Jenny Verner will be performed at The Linen Hall Library on September 30. Full details at Linenhall.com.