TERENCE Davies, who died last week aged 77, is a strangely singular figure in British film history.

He made some truly beautiful and evocative films, all deeply personal and often anchored firmly in his Liverpool upbringing, yet it’s hard to think of other film-makers he has influenced down the years. The art that Davies gave us was uniquely his and his alone.

Steeped in sentimentality and in awe of a simpler time with simpler ways, his films weren’t for everyone but immerse yourself in them and the rewards are many.

As the world thunders wildly into chaos there’s a comfort to be taken in his best work.

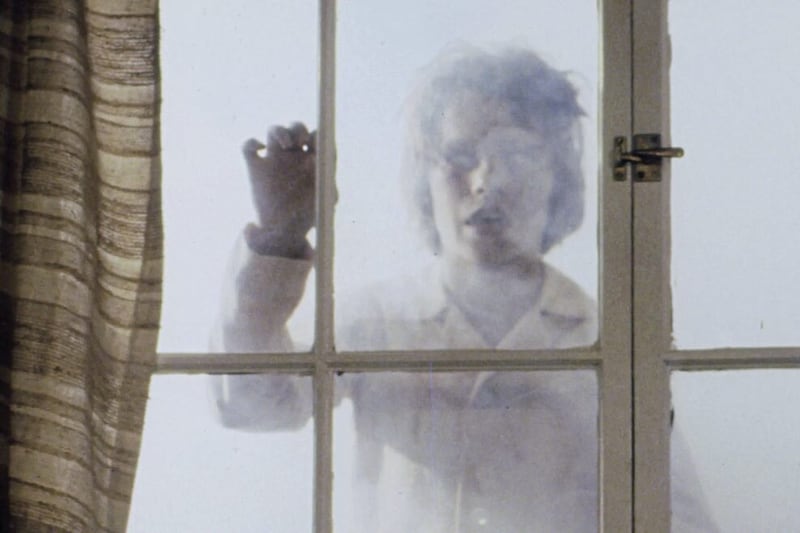

Take something like Distant Voices, Still Lives (1988), for example. A non-linear collection of personal memories of old songs his family would sing when he was a child, it drifts along on a melancholy breeze but also manages to make you feel uneasy at times with its acute observations of a troubled childhood in the Davies homestead.

The sometimes obsessive nostalgia hides a darkness that is all the more shocking when it rises to the surface. It’s a contemplative piece quite unlike anything else in British cinema history.

Even better is The Long Day Closes (1992). A hugely evocative study of the director’s Liverpool childhood as filtered through his beloved music and movies, it’s so personal it almost feels like finding someone’s private diaries and surreptitiously leafing through them while the writer is away. It’s a touching and deeply moving film in every way.

Given that the film industry is often the playground of the rich and entitled, Davis was a resolutely working class director and that adds a power to his work that sets it apart from the norm as well.

There’s little of the political drive that marks out, say, a Ken Loach but instead an ordinariness and an ease with displaying the everyday that impresses.

For the first decade and a half of his professional life Davies focused solely on his early days growing up in 1950s Liverpool. The youngest of 10 children, only seven of whom would survive into adulthood, he’s a kid out of line with the world around him much of the time.

He never quite fits in either at school or in the Catholic Church that looms large over his days growing up as a confused gay boy in a world where such inclinations were pushed firmly into the shadows.

You can feel his awkwardness and anxiety in just about every frame of his early work but more than anything you can feel his love of art. Movies and music provided a portal to a better world for the young boy and that deep passion shines through everything he made for the screen.

There is much to savour in his earliest offerings, from his experimental beginnings to the so called Terence Davis Trilogy that gave us Children (1976), Madonna and Child (1980) and Death and Transfiguration (1983), but his most impactful work has to be The Long Day Closes (1992).

Complex, conflicted, but made from love, it’s a fitting tribute to a cinematic life less ordinary.