THE end came quickly: one night, August 9 1971. After weeks of confrontation, the Stormont government was desperate and, in its desperation, sought London's approval and military muscle for the one measure that it hoped would restore order.

Internment, imprisonment without trial, was introduced, 300 Catholics arrested in a series of early morning swoops. Ballymurphy, as ever, was in the forefront.

My father set out for work but turned back when he heard about the raids. "Internment's in" was all he said. He and my mother discussed what to do and then they joined the others at their gateposts talking through the implications of events.

By lunchtime, the debate was becoming academic. Large crowds from Ballymurphy and Springmartin taunted each other across the main road. Soldiers who had reinforced a church hall near the bottom of our street with barbed wire and sandbags were edging trigger fingers, trying to communicate with outlying patrols scattered around the district.

What few police there were on the ground were never going to hold back the crowds and by that stage most Catholics saw them simply as the armed extension of Protestant mobs. An appeal for calm from the curate was greeted by jeers.

The first flights of stones, like some portage of medieval arrows, came over the rise from Springmartin, hitting the back of houses in Springfield Park. Windows smashed. Everywhere was panic. Some ran with children, some ran with bottles and stones, and some just ran. The main road was far too dangerous, so the field where we played became the only escape route for terrified adults trying to shepherd their children to safety. Families streamed across the little river's stepping-stones, taking with them all the belongings they could carry.

A small group of men, my father included, had to use a chair to lift an eighty-year-old woman over back hedges. All the while, they watched soldiers taking up position, aiming their rifles from the rooftops of the Springmartin high rises. Not long after, a loyalist crowd, emboldened by the lack of resistance and frustrated by the even match on the main road, started to come through the back fences of houses at the top end of the street, yelling and whooping to announce their presence.

There are many versions of who fired the first shot. As good as any is the account that has an IRA man venturing into Springfield Park and shooting his pistol over the heads of the mob from Springmartin. My father always said he did not know. Someone in a group attacking the upper end of Springfield Park produced a shotgun and fired at fleeing residents. My father was running towards the cover of our home with the baby of a neighbour who was a couple of paces behind with another child by the hand and another in his arms. The neighbour took the worst of the blast, but my father was hit as well. Soldiers in the church hall fired repeatedly, scything down civilians on the Ballymurphy side of the road. They killed two men, fatally wounded another and shot dead a mother of eight.

In the field, a woman stood still, paralysed with fear. Another neighbour was crawling in the tall grass. The soldiers on top of the high rises fired at him, searing a gouge across the small of his back. He screamed from the pain. The priest's house was opposite. He saw the wounded man and went to him waving a white cloth. The soldiers shot him. In the field where we played, the soldiers shot him. He got up on one knee. They shot him again. A man trying to help was killed as well. Others carried away the bodies on doors used as makeshift stretchers. High velocity rounds ploughed furrows through the earth of the field where we played.

In our home, my mother and father and some forty neighbours lay on the floor. It was one of only two houses safe in terms of the angles of fire. The unpredictable acoustic ebbed and flowed in waves hitting the distant streets; the pings and whines rattled our very slates. Like the face of an amplifier, the mountain vibrated back each crack, smack and roar. One round spat through the metal coal bunker at our back door.

At dawn, save for a baby crying and the bark of a distant dog, there was silence.

"There had been that much shooting I thought there would be bodies all over the street," my mother said.

The morning lull was followed by more chaos. People fled. Flatbed trucks were arriving, taking away box loads and bedding to 'refugee centres', the term suggesting some element of organisation where none existed. My father carried what he could up and down to the lorry sitting at the gate. It collected our clothing and some light furniture, bric-a-brac covering boxes where a few items of real value were buried. While my father put his arm around my mother, the truck pulled away, a mix of two families sitting on top of detritus shouting instructions and directions to relatives running along behind.

The following nights were spent on the floor of my grandmother's house. All of us lay on mattresses brought down from bedrooms judged too vulnerable to the gunfire. It started just before dusk. We saw some tracers, high and harmless. Oddly peaceful amidst the shooting, the army fired a couple of flares. Hung from parachutes, the flares dragged phosphorous false daylight across the sky. In their brief flickering light, I saw the pickled bruise marks of the shotgun pellets on my father's back, his skin just broken.

It took three days for things to calm sufficiently for them to get the information to go and retrieve our belongings. The 'refugee centre' was a primary school in one of the estates beyond the Falls. It rained steadily, a dank steamy summer rain. Families were scattered across the school hall on bedding of all shapes and sizes. There were a few boxes there, but nothing of my parents'. As they left, my mother remarked on some rags piled in the corner of the schoolyard. "God help whoever owns those," she said.

Then she noticed, on top of a sodden coat, a tiny item familiar to her, a softstone sculpture of the Virgin Mary. It had belonged to my father's mother. Its glass dome sat alongside, undamaged. My mother pulled away the rags. They were my father's dungarees. Underneath were a few things we had owned. Most, though, was gone, looted. My parents returned to my grandmother's house carrying two boxes. A few toys, a few photographs and some cutlery, including an apostle spoon given by my grandmother, were all there was to salvage from more than a dozen years of married life.

"We got out alive son and that's all that matters," my father said.

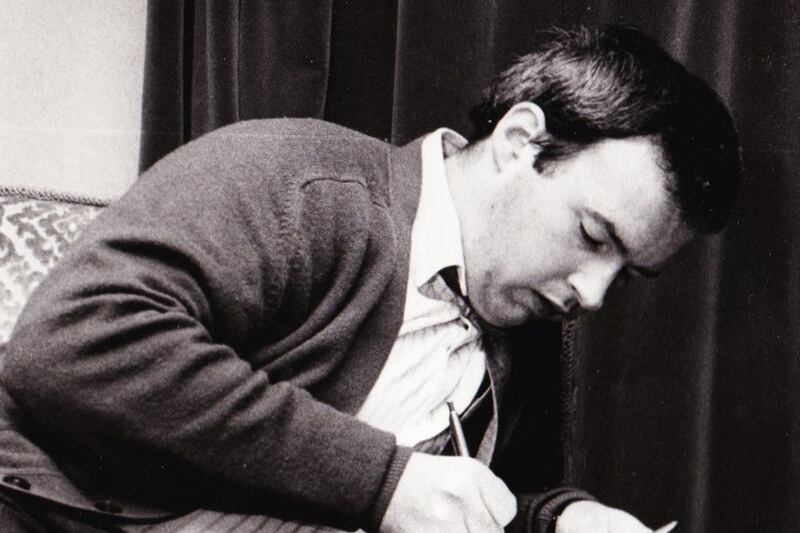

It was two months before my mother told me that my father's camera was one of the items stolen. He never took another picture.

Belfast Aurora: A Memoir of a Falls Childhood, 1971-1973 by Seamus Kelters is published by Merrion Press, £14.99. merrionpress.ie