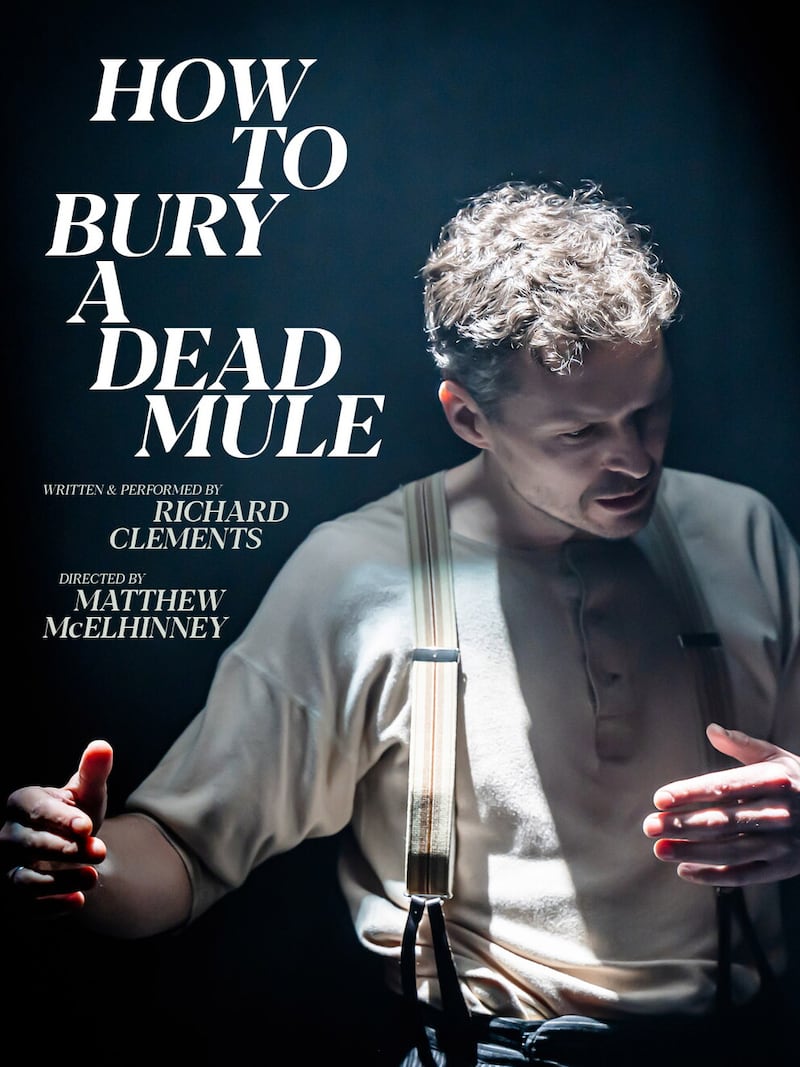

THE Second World War generation is dwindling, but anybody who sees Richard Clements' brilliant one-man play How to Bury a Dead Mule will feel they have time travelled back to the 1939 to 1945 conflict.

This harrowing, very human account of what happened to Clements' grandfather, Norman, who enlisted in the Royal Irish Fusiliers while under-age, is heading to the Edinburgh Fringe next month.

Writer/actor Clements (49) says he remembers hearing his granda's wartime stories from a young age:

"I was about eight and loved hearing them, even though I didn't enjoy history at school. We'd say 'Tell us about the war' when we spent fun, chaotic weekends with my grandparents."

But these were not cosy bedtime tales as the title of Richard Clements' drama suggests. Norman Clements narrowly escaped death on an Italian minefield and witnessed horrors that coloured the rest of his life.

He survived a bullet that narrowly missed his face, saw fellow soldiers mutilated under attack and encountered the titular problem of dealing with a dead mule killed by enemy fire. The worst moment came when Norman's six man detail was cornered and bombed in Italy – he was the only survivor.

Clements observes: "There is a line in the play when he refers to 'the savagery, the inhumanity' and wonders why he survived."

Read more:

Review: How To Bury A Dead Mule - After war, battle wages in the mind

Richard Clements on powerful, personal PTSD-themed show How to Bury a Dead Mule

Stage hit How To Bury A Dead Mule heading to Edinburgh Fringe - via Antrim

For him, it was not so much 'war and peace' as 'war and post-traumatic stress disorder'.

His grandson says now: "Unusually for somebody with PTSD or shell-shock, he wanted to talk about it, to make sense of it."

The play opens with Norman, played by Clements, rifling through boxes in his care home bedroom. We see the problematic re-entry for the man now haunted by a re-run of his experiences.

As Clements says, this aspect of the play was really brought to life by support from the Northern Ireland Screen Digital Film Archive. "They gave me access to wartime images for free and have supported the play."

The result is a true portrayal of the way Norman's brain attempts to process the experience, yet cannot. We see flickering pictures onscreen as the soldier's imagination flicks the switch of his war on and off.

Asked what was difficult to write, and what was straightforward, Clements says: "Some of the traumatic material was tough, but I wanted to get it down."

He and his family have recently returned from an emotional trip to Monte Cavallo, the area his grandfather fought in during the Italian campaign of 1944.

"It was a pilgrimage," he says.

"The war cemeteries are elsewhere, and there is nothing there to indicate the minefield my grandfather escaped from. It was affecting, and, as we got out of the car, my 12-year-old son Nico saw there was a single flower growing on a rock: it was an orange poppy.

"It felt like a kind of closure."

Indeed, Clements' grandfather Norman never made it back to Italy himself, but was taken by family members to remember his war during a trip to Normandy.

Clements admits that writing the play was an emotive experience: "I'd wanted to do this for some time and got the opportunity in lockdown, when you couldn't act in theatres," he explains.

"So I began, writing something every day."

In fact, the material is so affecting that some of his relatives haven't felt able to see the play, as he explains:

"Yes, one uncle hasn't seen it as it would be too painful. Also, my play is quite theatrical, which might be hard for somebody who isn't a regular theatregoer."

But Clements did collaborate with one family member: his mother Doreen, Norman's unofficial archivist.

"She kept notes of his stories which I used, and she read the play, which she's seen everywhere. In a way, she had to approve and sign it off."

Happily, she liked it, and will soon travel to Edinburgh to see her son's work.

"She is proud of it and I think it has evolved as it's gone on."

Clements says that this project is one of those creative pieces of work that has a life of its own.

"Every time I think it's time to move on to something else, another possibility emerges, like taking it to Edinburgh. And of course, it would make a great film, so who knows where it might go."

Not explicitly a pacifist work, How to Bury a Dead Mule nevertheless makes a powerful anti-war case by its very plot. Clements adds: "I think when you look at what happened, you think 'why do we send men and women off to combat zones?'.

"Recently, I watched a programme about the fall of Kabul, and we still don't know how to deal with these events."

Norman Clements' troubled homecoming is one of the most moving passages of the play. The guy who has seen things he will never forget at too young an age – like so many others, he enlisted at 17, having fibbed about his birth date – arrives back to no welcome at all.

His family have not turned up to take him home and he has to take a taxi from the station to his old house. It's psychologically unbearable.

Norman Clements was in and out of psychiatric care, which in the post-War era was fairly primitive.

Clements comments: "They didn't have the sort of drugs or treatment we have now. He would go to mental hospitals at time and ended his life in care. He couldn't work and there were tensions."

The way Norman's wife found it hard to deal with this damaged hero is beautifully handled: it was during a period when he had returned home from the War on leave that she realised he was suffering from what we now know as PTSD.

"We think that's when she realised he was ill and was why he wasn't met at the station," says Clements.

Although How to Bury a Dead Mule is specifically about the mid-20th century, with spot-on lingo and period references, it has a universality too.

Richard Clements recalls one person relating the trauma to Northern Ireland's more recent conflict.

"A woman attended the play last September on press night, then came up to me at the end to say that it reminded her of the trauma of growing up in Belfast during the Troubles," he tells me.

"She said she still suffered from PTSD."

Stirring up memories can be cathartic and this is a nice spin-off from the drama.

The Bangor-born writer and actor reveals that when How To Bury a Dead Mule opens in Edinburgh on August 2, he hopes to tap into his audience's actual and ancestral memories of conflict and how they have been affected.

"I'd like to put a card on each seat and get people to jot something down, then maybe have a kind of group discussion afterwards."

Although Clements' focus is currently on the play about his granda's war, he also has other projects planned, and is acting in Tinderbox's autumn production of the absurdist drama Rhinoceros.

"I play Berenger, the main character," he reveals.

This should be revelatory, but you sense that How to Bury a Dead Mule, another absurd story in its way, hasn't disappeared for good.

:: How to Bury A Dead Mule runs from August 2 to 27 (excluding August 16 and 21) at the Pleasance Dome in Edinburgh. Tickets and full information via pleasance.co.uk