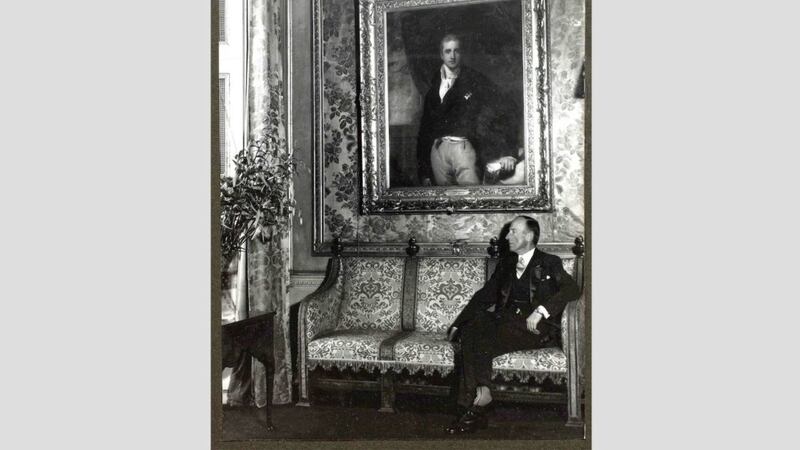

CHARLES Stewart Henry Vane Tempest Stewart, seventh Marquess of Londonderry, played a central though now largely overlooked role in political life in the immediate post-partition years of Northern Ireland, serving most notably as the first minister of education from 1921-1926. A century later, what can we learn today from this intriguing figure?

The seventh Marquess (Londonderry) was born on May 13 1878 into one of the wealthiest and most powerful Anglo-Irish aristocratic families, with houses at Mountstewart, Park Lane in London and Co Durham (location of the family’s rich coalfields).

A cousin of Churchill and on first name terms with the king, Londonderry was inspired by his ancestor, Viscount Castlereagh (the second Marquess), who had been instrumental in securing the passage of the Irish Act of Union with Britain in 1800, and had orchestrated the Congress of Vienna in 1815.

The sixth Marquess (Londonderry’s father) had also served as Lord Lieutenant of Ireland (1886-1889) – his son recalled entering Dublin as a young boy in a state procession to cheering crowds.

After schooling at Eton, officer training at Sandhurst and a military career in the Royal Horse Guards which included active service at the Somme, Londonderry entered politics reluctantly and out of a sense of duty to his father who encouraged him to stand for election to parliament at Westminster in 1906.

Having accepted Sir James Craig’s invitation to leave Westminster and join the new Northern Ireland government, Londonderry’s career as leader of the Senate and first minister of education in Northern Ireland is often derided as a failure.

He is perhaps best remembered for the 1923 Education Act (also known as the Londonderry Act) which was a bold piece of legislation for its time. If successful, the act would have created a school system free from religious denominationalism under local education authority control but his vision was ultimately thwarted by trenchant clerical opposition from both sides of the community.

In the first instance, resistance came from the Catholic Church whose suspicions were raised from the outset by the potential loss of influence if they were to transfer full control of their schools to the state, even if it would have meant access to capital funding.

Archbishop Michael Logue wrote to Londonderry rejecting his invitation to nominate Catholic representatives to the Lynn Committee (established to propose the detail of the educational reform) in September 1921 fearing that the committee would be used “as a foundation and pretext” for an “attack… against our Catholic schools”.

Londonderry wrote to the Lord Lieutenant (Viscount FitzAlan – a Catholic) invoking his support and claiming that he would “do anything to raise this committee above all political and sectarian prejudices” but to no avail.

Instead, the Catholic clerical primary school managers met in Dublin in October 1921 and made their position quite clear: “in view of pending changes in Irish education, we wish to reassert the great fundamental principle that the only satisfactory system of education for Catholics is one wherein Catholic children are taught in Catholic schools by Catholic teachers under Catholic auspices.”

The subsequent 1923 Education Act, based largely on the Lynn Committee’s recommendations but with an amendment by Londonderry to prohibit local education authorities from providing any denominational religious instruction in transferred schools, also subsequently provoked a growing campaign of resistance led by the Protestant churches who feared that the reforms would create “godless” schools through preventing the delivery by teachers of “a programme of simple Bible instruction” in transferred schools.

The Protestant churches were also incensed by the stipulation in the act that forbade the appointment of teachers to transferred schools based on religious affiliation.

While Londonderry was intent to ride out the bitter storm, his fate was eventually sealed when Craig withdrew his support, fearful of the mounting campaign which was threatening to split unionism.

Disillusioned by the opposition to his education reforms, humiliated and frustrated by his growing alienation from the unionist leadership, and increasingly distracted by the impact of the turbulent general strike on his Durham coalfields, Londonderry resigned in early 1926. His subsequent ministerial career at Westminster in the 1930s would be remembered most for another failure: his support of appeasement with Hitler, an attempt, he felt, to bring lasting peace to Europe and avoid a repeat of the horrors of 1914-18.

So how should Londonderry’s term as minister of education be remembered?

Admittedly, his reforms came to little, despite his best intentions. Had they succeeded, however, they could have brought a single, non-denominational education system which still eludes us a century later.

Should he be viewed as a progressive visionary ahead of his time, thwarted only by clerical self-interest and internal unionist insecurity, or rather as a detached patrician too far removed from the everyday realpolitik to pre-empt the partisan feuding of a deeply divided post-partition Ireland?

Perhaps he was both, and his experience of Northern Ireland politics certainly left him bruised and frustrated, but notwithstanding his flaws, I would argue that he should be given credit for his audacious plans to overcome historical divisions and create a common education system for all.

Just think, if his plans had succeeded, where would our education system be today?

:: Dr Noel Purdy is director of research and scholarship at Stranmillis University College, Belfast.