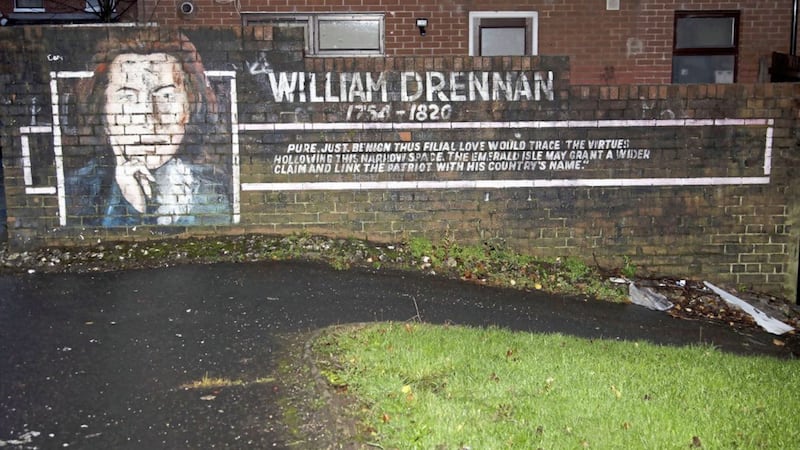

WILLIAM Drennan was born in the manse of First Presbyterian Church in Rosemary Street, Belfast, in 1754. He became a doctor, poet and political radical and a founder of the Dublin Society of United Irishmen in 1791.

The new society lamented ‘the brazen walls of separation’ which had been erected among the inhabitants of Ireland by distinctions of rank, property and religious persuasion. Drennan composed the society’s oath which had as its purpose "the forwarding of a brotherhood of affection, a communion of rights and a union of power amongst Irishmen of every religious persuasion".

Many of the society’s addresses were drafted by Drennan and he was by far its most active and able literary propagandist.

Drennan and his sister Martha McTier wrote to each other regularly for more than 40 years. Their letters contain fascinating details and insight as well as scintillating gossip concerning many of the leading figures on both sides of the revolutionary divide in Ireland at the close of the 18th century.

The pair took a keen interest in the politics of Ireland, Britain, France and America. They warmly supported the American and French revolutions. Drennan was delighted when the Americans defeated the British at Saratoga in 1777 and Martha sang Over The Hills And Far Away when the Duke of Brunswick was defeated at Valmy by the revolutionary French army in 1792.

Drennan was an influential figure in Dublin radical circles and he wrote often to Martha’s husband Sam McTier. Through Sam he exercised a profound influence on the policy and strategy of the Belfast United Irishmen.

Although Drennan advocated a brotherhood of affection between all Irishmen, a consensus persists among historians that he was an anti-Catholic bigot with an obsessive dislike and mistrust of Catholics. May Tyrants Tremble debunks this consensus.

Drennan’s friend Archibald Hamilton Rowan made a sensational escape from Newgate prison in 1794. Rowan had been entrapped in a treasonable conspiracy with an agent of revolutionary France. Drennan denied all knowledge of the affair. Yet he had read the document which Rowan had passed to this agent and he also had accurate information about how Rowan had managed to escape from the prison and the country.

A few weeks later Drennan was arrested on charges of subversion. He was tried and acquitted. Many historians have claimed that after his trial Drennan was considerably chastened and from that point on gradually withdrew from the United Irish movement.

In fact, he continued to produce literary propaganda for the United Irish society. For reasons of self-preservation in the climate of oppression, much of his work appeared anonymously. Some of the most treasonable material to appear in the Press, the Dublin-produced Society of United Irishmen newspaper suppressed in early 1798, was written under the pseudonym 'Marcus'. My investigations have uncovered significant evidence which leads me to believe that Drennan was Marcus.

In September 1796 William Orr, a young farmer from Farranshane near Antrim town, had been arrested and charged with administering the United Irish oath to two soldiers of the Fifeshire Fencibles. Orr was a New Light Presbyterian and had occasionally written to the Northern Star, the society's principal newspaper, produced in Belfast.

He was held in custody for more than a year before his trial in October 1797. Although the jury was rigged, they could not agree their verdict and were locked away from seven at night until six o’clock in the morning. During the night, they were plied with bottles of whiskey and the chairman of the jury afterwards claimed he had been intimidated into bringing in a guilty verdict against his wishes.

William Orr went to the scaffold on October 14 1797 on an open common a mile from Carrickfergus. The streets of the town were deserted as "the townsfolk showed their contempt for an act of shameful injustice". As the rope was placed round his neck, he exclaimed, "I am no traitor. I die for a persecuted country. Great Jehovah receive my soul. I die in the true faith of a Presbyterian."

The execution inspired Drennan to compose the poem entitled The Wake of William Orr which many regard as his best work. The following year, when the long persecuted and oppressed Northern United Irishmen rose in rebellion, their battle cry was ‘Remember Orr’.

In the spring of 1798 when most of Drennan’s friends were in prison he compared himself to "a solitary ninepin when all around him had fallen".

While he did not condemn those of his friends who had absconded to avoid arrest, he assured Martha, "I am still at my post and here I shall remain."

When Drennan died in 1820, in fulfilment of his dying request, he was carried to his grave in Clifton Street cemetery by six poor Catholics and six poor Protestants. The union of Irishmen which Drennan advocated evaporated as Orange unionism and Catholic nationalism went their separate ways in mutual animosity.

Two hundred years have passed since William Drennan’s death. In all that time Drennan’s hometown of Belfast has known sectarian hatred and intercommunal tension, often exploding into murder and mayhem. The 'brazen walls of separation' are no longer just the elegant metaphor honed by William Drennan; they are an ugly physical construct called with, no sense of irony, the 'Peace Wall’.

These brazen walls of separation have been erected at the request of residents on both sides, to keep Belfast’s most deprived citizens apart.

:: May Tyrants Tremble: The Life of William Drennan, 1754-1820 by Fergus Whelan, is published by Irish Academic Press (£25), available to order at iap.ie