STEPHEN Rea has just finished a six-week run of Belfast playwright David Ireland’s intense Cyprus Avenue, in the Royal Court Theatre in London, and is struggling to find his usual pitch and rich vocal tone.

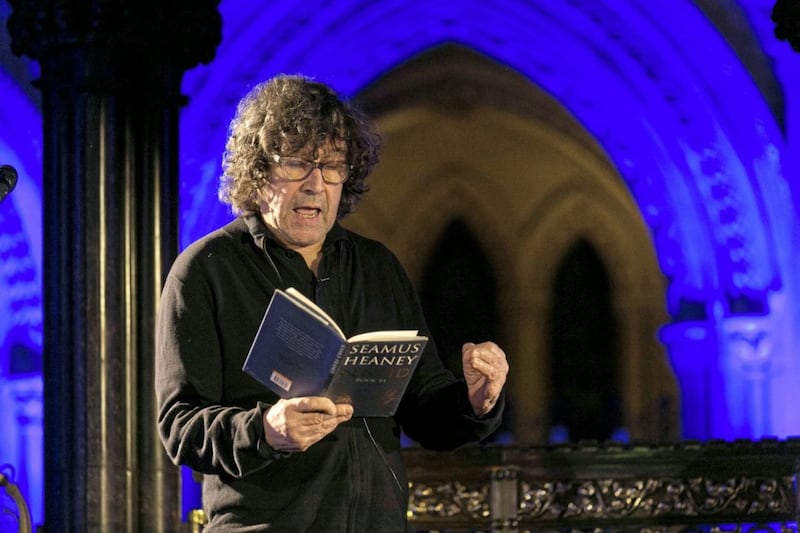

"My voice is very, very tired and I’m supposed to be resting it," he says apologetically – before heading back into rehearsals for the upcoming Belfast performance of Seamus Heaney’s translation of Virgil’s Aeneid Book VI, with musical collaborator Neil Martin.

At 72, the versatile, award-winning actor concedes it "does gets harder", but, hoarse or not, the Belfast-born star of groundbreaking 1992 thriller The Crying Game finds it difficult to stay silent for long – especially when Seamus Heaney is calling.

His enthusiasm for this latest project with Belfast composer and cellist Martin is palpable and the pair are excited to bring the special adaptation of words and music to their home city for one performance at The Mac tomorrow.

The fact the translation was Heaney’s last piece of work before his death in 2013 brings extra poignancy: Rea and Martin were both close friends of the poet through the Field Day Theatre project created in 1980 as a "cultural and intellectual response to the political crisis in Northern Ireland".

"The only thing I was ever any good at school was reading aloud, but most people thought it was a travesty of their manhood to read poetry," Rea reflects with sincerity as well as humour. "While I found Latin difficult, I always loved the rhythm of poetry and one of my greatest pieces of advice came from [playwright] Samuel Beckett who, when I once queried the meaning of a line in the play, Endgame, said, ‘Don’t think about the meaning, think about the rhythm’.

"It’s genius, really, because language is rhythm. He [Beckett] also pressed upon me the role of ambiguity and that is how I have approached acting ever since.

"Poetry in itself is ambiguous and I think the thing that kills poetry is just being too literal; it’s really not a literal art form, it’s an art form that probes your imagination and allows you to travel with it."

An epic poem in Latin penned by ancient Roman poet, Virgil – or, to give him his full title, Publius Vergilius Maro – Aeneid Book VI tells the story of Aeneas’s descent into the underworld to look for his father, but while a "Latin original", Rea says Heaney’s treatment of the text exudes a distinct northern Irish type of feel and beauty.

"That’s what is so beautiful about Seamus's translation," Rea expands generously. “He takes you right back to Bellaghy when he meets his father – it’s really like an exchange between two south Derry men. It’s very, very beautiful."

The adaptation, which has been performed in Dublin and New York to high acclaim, first came to life after the now Dublin-based Rea was asked by Kilkenny Arts Festival in 2016 if he would do a reading of Heaney’s Aeneid.

He was enthusiastic, but thought there should be music to accompany it and wanted Martin as the musical collaborator.

For the north Belfast cellist (and also uilleann piper) who has performed everywhere from the Carnegie Hall in New York to the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, composing a "virtual conversation" on stage between Heaney's spoken words and a musical instrument proved the quintessential "dream project".

"It has a kind of improvised thing about it, so each time we perform the poem, there is something a little different to discover," Martin enthuses. "You hear new phrases, new words, new ideas, new colours that Seamus created. It’s ever-evolving and it's a glorious piece of text to work with."

Rea is equally effusive, describing Heaney's Aeneid as "an extraordinary piece among an extraordinary body of work" and he is happy to lose himself in the classics. He describes it as a sort of letting go; a release "from the narrowness of the situation in the world that you’re trapped in".

Having said that, he doesn’t worry too much about the underworld, per se.

"Am I going to meet my father?" he ponders. "I don’t know. I don’t know what one feels about that. Increasingly, our world insists on the literal and there’s a feeling that it’s impossible to believe in things like the spiritual world.

"Religion hasn’t been a great help in that so often it has been authoritarian rather than poetic, but I’ll go anywhere Seamus invites in the poetry..."

However, he has, he says, by consequence of his seven decades, been to many funerals and believes the most up "uplifting" thing has always been the music and the poetry that people choose to read.

This poetic side of Rea sits at some distance to his other great love: working for the camera in film and TV – although he maintains the intensity and the emotion are the same with both.

His latest was historical revenger thriller Black '47, released last year and set in 1840s famine-ravaged Ireland, but this master of ambiguity and unaffected everyman takes roles as they come and feels just as "blessed" to be associated with great Irish playwrights and poets as with films such as Michael Collins (1996) or Interview With The Vampire (1994).

"I don’t go about thinking, ‘Oh, I’ll have to play King Lear some day' ", stresses the actor who studied English at Queen's University Belfast before training at the Abbey Theatre School in Dublin. "I do love working for both live audiences and the camera, but I find film more therapeutic.

"The pressure in theatre is like an intense, religious ritual where you purify your soul all day and then you hope to achieve something as you stand at the altar of your destruction…"

Next up is new project The Stranger, with Netflix, a Harlan Coben thriller starring Siobhan Finneran and Hannah John-Kamen, and also featuring Jennifer Saunders and Anthony Head – but he is not allowed to talk about it yet.

"I've always known I wanted to act since primary school days, even though it seemed impossible to be an actor back then," he says. "I said to my sons many years ago that I've spent my life doing what I wanted to do and that's what everyone should try to do. I know I've been lucky."

Rea, who had his two sons with ex-IRA woman, the late Dolours Price (the couple divorced in 2003), is well known for his deep passion for socialist politics and he hopes to bring these centre stage again in a special 40th anniversary celebration of the Field Day Theatre Company in 2020.

"I really want to stage a different kind of literary festival in Derry to mark the occasion," he says, his fading voice picking up some volume again. "It will focus on people from troubled areas across the world, not just Ireland, and give them a voice.

"I have a working title for it – No Borders – and, unlike Brexit, it will be all about including and not excluding people. I am very interested in how frequently people in dire situtations try to write their way out of it, with their poetry, with their words. This festival will be their platform."

:: Aeneid: Book VI is at the MAC on Sunday April 7 at 8pm – for more information and booking see themaclive.com