WEE Dan McGourty was in goal for St Gall’s when they came to Bellaghy for a game in 1982.

The Belfast men were two points down with time running out. PJ O’Hare gave the call from the line for McGourty to go ahead.

“He came right up the field and put the ball in the back of the net, and they were squealing: ‘The goalkeeper can’t score!’” O’Hare recalled in a recent chat with Brendan Crossan of this parish.

The former Antrim manager’s philosophy on goalkeepers was that if they couldn’t solo the ball, they couldn’t play on his team.

Goalkeeping has moved in the kind of very small increments we associate with any form of evolution within the GAA, but that’s been a worldwide trend in sport.

It’s barely a full generation gone since Peter Schmeichel was considered the prototype for goalkeepers. Big man, brave, huge hands, loud. He was woeful with his feet though.

This is the era of Ederson and Manuel Neuer, who match the traditional aspects of goalkeeping with the ability to play ball.

Bernardo Silva of Manchester City remarked last year that his number one could easily play as a holding midfielder. If there’s a better passing range in the Premier League than Ederson’s, we’ve yet to see it.

We’ve always preferred our goalkeepers to be more reliably bog-standard.

Keep it out and lace it out. Job done, for the first century of Gaelic football’s existence.

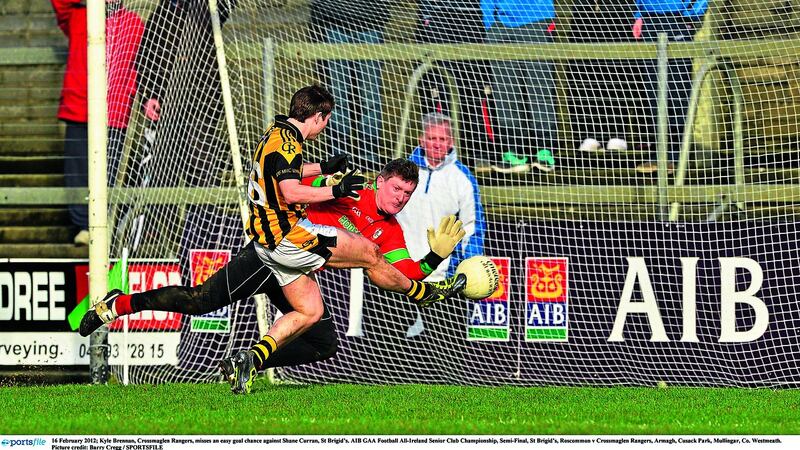

Shane Curran was the maverick who broke the mould. He recalls being fascinated by Martin McNamara from his neighbouring Galway, who was the first man he’d seen noticed the kickout in a different way.

“There is no room for fat lads in goals any more,” McNamara himself would note in an interview three years ago.

There are firsts, and there are the firsts you notice yourself.

Adrian McGuckin’s teams at St Patrick’s Maghera were often instructed to kick the ball to the wings long before it was fashionable.

No conversation on goalkeeping is complete without bowing at the altar of Cluxton.

But Shane Curran was definitely different. At the time, the standard description of his ventures out of goal ranged from bemused to uncomplimentary.

A couple of decades on, and we’re after witnessing another leap forward in the evolution of goalkeeping by two men who took the leaf from the former Roscommon goalkeeper’s playbook.

Niall Morgan and Rory Beggan were at the centre of the post-match discussion from Saturday’s Ulster final in Croke Park.

Anyone who has studied both would consider it nothing unusual to see them involved in open play. What was different was how they went full-out on every kickout, standing at midfield, and eventually contesting them in the air.

The game had inched towards that. In this summer’s Ulster championship, aside from those two, we’ve seen Shaun Patton, Odhran Lynch, Raymond Galligan and Blaine Hughes all operate in the same pocket on the opposition kickouts.

Saturday’s difference was Beggan contesting the ball. And both times he did, Tyrone won it. The second time required a miraculous recovery in which the Scotstown man got back to retrieve the ball from Mattie Donnelly as he thought about which spot he’d pick in the Hill 16 goal.

Balancing risk and reward is always the trick. In terms of goalkeeping, that runs in a thread from selecting your number one through to what you’ll ask him to do.

From shot-stopping, dealing with high balls and kicking it as far as you could pretty much the only priorities for a generation, the game has changed and goalkeeping has changed with it.

Ultimately, the game will dictate what goalkeeping does next rather than vice-versa.

“Where can it go?” wonders Curran.

“The evolution of the goalkeeper will be around the evolution of the team. I can see a game where you have 10v10 up to halfway and four or five men in the full-forward line, and end up a bit like basketball, up and down the pitch.

“The goalkeeper then may have to be a really good shot-stopper because there will be more goal chances created.

“I think the goalkeeper will evolve by how the game evolves, not the other way around.

“If Monaghan had conceded two goals on Saturday from Rory going up the pitch, coaches would start to question.

“And that will happen, because teams are gonna figure this out very quickly, let’s get support up quick and it’s only a punch into the net when there’s no ‘keeper.

“And then coaches start to think do they need to just go back to having a really competent goalkeeper.”

Beggan’s leap at midfield could very well have ended Monaghan’s Ulster final dream. But then winning the ball could have salvaged the game. Rewards are earned by risks. It’s just balancing the two.

When Castlerahan played Eoghan Rua in an Ulster Club game three years ago, the first half was disastrous for the new Cavan champions.

Six points down and a man down, Donal Keogan allowed they’d be as well to lose by 12 as six.

He pushed everyone up on Coleraine’s kickouts and that meant his goalkeeper, Jamie Leahy, coming out and playing at full-back. They cut the gap back to two before getting caught on the break late on and losing by six.

“We’d played Cavan Gaels in a league game that year and they got 1-7 from their own kickouts. We played them in a league final and we hadn’t really been pressing, so we said we’d commit people forward.

“If we did that there’d be big holes at the back. It depends on the mobility of the goalkeeper and a load of different things. It was about stopping Cavan Gaels getting out.

“It’s really enjoyable for an audience but your kickouts are massive, you have to be winning them and getting scores off them. “It’s great to have the ‘keeper out on a high press but it’s dangerous too.”

Niall Morgan was the goalkeeper for Ireland in the International Rules in 2017. Brendon Goddard was chosen as Australia’s netminder, a position they don’t have in the AFL.

A full-forward line of Conor McManus and Michael Murphy would terrify most teams but not the Aussies. They often left Murphy unmarked and had Goddard out marking McManus.

They never looked like paying for the risk. It allowed them to own the ball and get spare men into the attack all through both games.

Morgan no doubt learned from that series but was already coming out the field at club level, and has subsequently graduated to full-time midfielder for Edendork.

There’s a definite debate over whether an inter-county goalkeeper is better playing his club football in goals or out the field, but seemingly no right answer.

The expectation on goalkeepers at club level has risen out of sync with the other 14 players. You’re expected to flight a ball into the run at chest height. If the opposition push up, you’re expected to have a bionic leg and kick the ball 80 yards over the top of them, because Patton can.

But it’s also become more enjoyable. More attractive to young players. Goalkeepers have almost become a star attraction.

Shane Curran always enjoyed it. He recalls a league game in Donegal where he set up a goal and Brian McEniff mused to him afterwards: ‘Hmm, this is different’.

The St Brigid’s man had the great advantage of playing his first decade of senior club football outfield. He was a county minor goalkeeper and played seniors in the early ‘90s but only went into goals for the club in his late 20s, though he’d been doing nets for Athlone in the League of Ireland as well.

Shaun Patton and Niall Morgan have their own top-end experience in soccer, while you’ve had the like of Graham Brody in Laois benefitting from his years of carrying ball out of goal for his club, Portlaoise.

He, as much as anyone, took it to a new level with the pace and frequency of his willingness to join the attack.

His hand in Laois’ equaliser against Wexford in the summer of 2018 seemed like a frantic late involvement but he’d been at it all day, and would keep at it the following summer, earning himself a deserved Allstar nomination.

Yet despite the emphasis on kickouts and now being able to play ball, there aren’t a huge line of serving inter-county goalkeepers that currently play outfield for the club.

The idea of the hybrid goalkeeper is grand in theory, but in practice?

“No team will win an All-Ireland with a hybrid goalkeeper who can’t do the basics,” says Curran.

“That will cost teams over time. A friend of mine asked me there if you’d put Shane Walsh in goal for Galway, and he wouldn’t get as much flakin’ and hardship, he could come out the field.

“Not a chance – if you put him in goal, Galway would be conceding three or four goals a game.

“Go back over the last 20 years of any team sport in the world, you will win nothing with a goalkeeper who’s not able to do the basics. Impossible. Won’t happen.”

His career with Roscommon was broken across the 1990s and early 2000s but even a decade after retiring, the howls of laughter and confusion in Breffni Park were unforgettable when Armagh’s Paul Courtney tried to emulate him in 2016.

A left-field choice out of nowhere, the outfield Ballyhegan player was thrown into goal. He started popping the ball off the tee and then going for the return, sallying up the pitch.

It was considered great amusement for an afternoon but not something a serious team would do.

Yet here we are now, just five short years on, and the whole idea has been transformed. You’re the odd-one-out if you’re not doing it now.

“I don’t see the hybrid goalkeeper being a runner unless you have the skillset of a goalkeeper, married to what you’re doing.”

Cluxton’s ability off the tee was second-to-none for years though Curran, perhaps rightly, argues that it was about far more than him.

Dublin had a greater level of fitness, they had more runners, they had big, athletic fielders and they had Croke Park every week.

David Clarke was the decade’s best shot-stopper. Patton has assumed the mantle as the best off the tee. Morgan and Beggan are the entertainers. The youth of today don’t know quite where to look for tomorrow’s inspiration.

But that they’re looking at the goalkeeper at all is a remarkable evolution of all of its own.