THE river valley behind Tom Beag Gillespie’s home stretches out for miles, and gives name to the land on which his family have lived for generations.

Srath na Corcra is the townland that sits up on the hill in Derrybeg, part of the Gaeltacht parish of Gaoth Dobhair which has done its best to reject its Anglicisation.

The ‘corcra’ are small, blue flowers that, when the land dries out in summer, grow up from the ‘srath’ (valley).

The tide comes in to his back door, from which he looks across on the island of Aranmore. Sitting low in the distance of the valley is the GAA club’s windswept pitches across at Magheragallon, where he’s done a huge body of work in sculpting the team that will take on Corofin this afternoon.

Tom Beag is 61. His youngest sibling Kevin is a monsignor in Letterkenny, while his other three brothers (they also have one sister) all emigrated to America in the mid-80s when the industries that had thrived for years around them started to die.

Plunkett and Joseph ended up in New York, while Eamon is up in Connecticut, carrying on the family trade.

He, like their father and grandfather, is a blacksmith. The Mac Giolla Easpaigs (to give them their Gaeilge) owned a forge at the top of the hill, just yards from their home, next door to which Tom Beag built.

“I felt somebody had to stay,” he says wistfully when the subject of why he’s still about comes up.

The family has always been of Gaoth Dobhair, but with the rest moved away and himself having no family, there won’t be any left when Tom Beag takes his leave.

“It’s sad but that’s the reality of it… yeah, that’s the way it’s gonna be.”

He tried London for a couple of years in the late ‘80s, but otherwise he’s been lovingly tied to a beautiful rural outpost which, like so many, Gaelic football has done a lot to hold together.

A considerable portion of his hours are spent at the club. He’s employed under a scheme by Údarás na Gaeltachta. They pay the wages and the club gets the work out of him, maintaining the grounds.

But of the evening, when he has the current minors or under-16s captivated by his zest, there’s no money in it. Just the sheer love of the game.

Gillespie’s uncle Danny holds the joint-record of eight Donegal SFC medals with Brian McEniff and Seamie Granaghan. His father’s other brother Eddie Beag has five, four as the starting goalkeeper, from the run that saw Gaoth Dobhair win 12 titles between 1935 and ’61.

And then they went away. Tom Beag played for 15 years himself, losing senior finals in ’77 and ’78 and winning an intermediate championship in ’85, but that wasn’t considered a high point in the club’s history.

Gaoth Dobhair was once a bustling factory town, where the likes of Comer Yarns and Telectron and his own employer until the mid-80s, German firm Dianorm who made radiators, had set up.

The side-earners for many were drawing turf and selling them to the local ESB station, which would pay a decent price and then use it as fuel with which to power the town’s electricity, or keeping a few cattle.

Tom Beag still draws the turf. At either end of the smouldering open fire are two armchairs. He pours the water from the tap into the old kettle and sets it on the gas ring to boil for tea.

He’s never driven and relies on his bicycle to pull him up and down the hill from the town to home.

For longer journeys, McGinley’s coach comes around from Annagry and lifts him at the old derelict petrol station that Eddie Beag once ran.

As the employers started to migrate their bases to eastern Europe, almost 4,000 people in the area lost their livelihoods between the mid-80s and the early 2000s.

That was part of the GAA club’s struggle. Tom Beag recalls the club losing four members of the Donegal All-Ireland vocational schools winning team from 1984, one of them an All-Ireland U21 winner three years later, to emigration when they were only just fresh seniors.

The current team has lost Danny Curran to Dubai, Jamie Reynolds and Eoin Ward to Australia. James Carroll had been in Dubai too, but timed his return home well.

That is the great unknown for this Gaoth Dobhair team. The young team that Tom Beag Gillespie helped build are almost all of university age. What becomes of their lives in the far west once they’ve qualified and have to start earning?

There are no guarantees. Talent wise, Gaoth Dobhair could be around for a long time. But if one or two or three have to go off to Dublin or Dubai for work and another few take their well-earned retirement, then who knows?

If that’s how it’s to be, well it’s been some journey.

*****

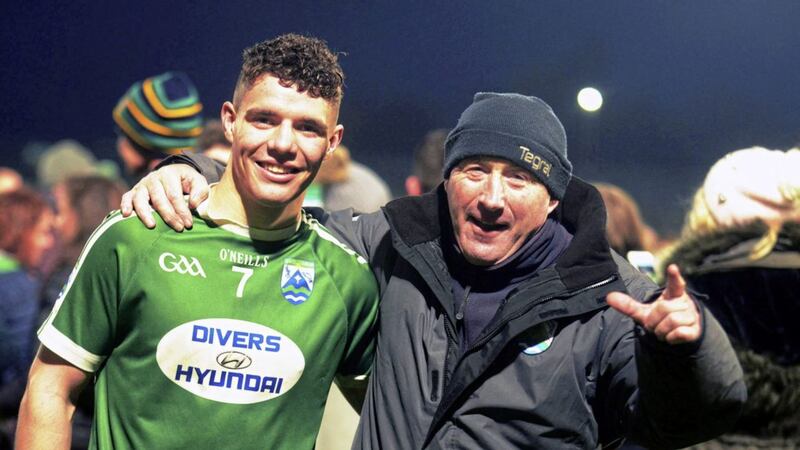

“I wouldn’t be where I am without him, he is the main guy in Gaoth Dobhair for us – that whole U21 team would see him as our coach, our manager, because he put a lot of time into us.”

Naoise Ó Baoill on Tom Beag Gillespie, December 2018

DONNCHADH MacNiallais. Brendan Ó Baoill. Tom Beag Gillespie.

You won’t see their names in the programme in Pairc Sean Mac Diarmada but without those three, none of this would have happened.

41 years, from 1961 until 2002, without winning a senior title was a long time for a club of their standing. There were all sorts of factors involved, with emigration and soccer top of the tree.

Gweedores Celtic and United are the two local clubs and for a time between the late ‘70s and late ‘80s, they were strong. Gaelic football in the town was weakened by that, and its neglect on the Derrybeg end of the parish.

There are still a few that tip at soccer during the winter, but it’s the secondary sport again. Tom Beag played himself, mostly for United, but his first love was the GAA club.

When Tadhg McGinley took on the manager’s job in 2002, he drew Tom Beag in to coach. When Tadhg took sick, Tom took the training as part of a team with Pearse Coyle, Alan Boyd and Bernard Boyle.

From 2002 until 2004, they won a Donegal SFC, two All-Ireland Gaeltachts, three Donegal Gaeltachts and a first senior league title since 1973.

But there wasn’t the depth of talent coming behind to sustain it, and so Gillespie, Ó Baoill and MacNiallais spearheaded an overhaul of the club’s underage structures in 2005.

It had many cornerstones, but one of them was the culture and language. They wanted the club to be true to itself.

Nowadays, everything conducted at the GAA club is done in Irish.

They took their under-14s for a weekend in An Gaeltacht down in Kerry in 2005, where they enlisted Dara Ó Cinneide in an ambassadorial role.

That involved him coming up four weekends a year for three years to take coaching sessions at the pitch. But the former Kerry captain could sense the importance of the cultural element.

“Culturally, more than anything else, it seemed like it was important for them to get someone from outside Donegal with a bit of Gaeilge that had achieved something and tell them they were doing the right things. And they were,” recalls Ó Cinneide.

In his mind, Tom Beag Gillespie is Gaoth Dobhair’s answer to his own clubman Liam Ó Rócháin, who was the guiding hand that crafted their run to an All-Ireland club final in 2004, as well as many a Kerry legend.

“Tom Beag’s an incredibly humble man, a quiet man, but his training sessions are absolutely brilliant. You could see the kids loved him, they’d do anything for him. He must’ve been exhausted after every training session because the enthusiasm he had, he was so vocal.

“The likes of Tom Beag is an absolute diamond. He is the GAA. I don’t want to sound trite or romantic about it, but that’s what it is. Otherwise there’s no point of it. They’re a rare breed and they’re becoming rarer because people are saying ‘what’s in it for me?’”

But as much as the trip to An Gaeltacht set Gaoth Dobhair up culturally, it was an eye-opener. They lost the challenge game handy.

St Eunan’s were always the underage benchmark domestically. When they met at under-12 level in 2008, Gaoth Dobhair took two teams down to O’Donnell Park, but the ‘A’ team were beaten by 40 points.

And yet a bit of indiscipline by a couple of players that day was dealt with by way of an internally imposed one-match ban.

There were standards being set.

Just two years later, they beat St Eunan’s in the league final, but when it came to championship there was still 15 points in it the other way.

Tom Beag, who’d taken them over at under-12 after Brendan Ó Baoill had put the man hours into their fundamentals, took the decision the following year to drop the team into the U16B league.

It wasn’t a wholly popular decision at the time, but the bulk of them were a year young for ‘A’ football. They had half a dozen replays across the year but got over Naomh Conaill in the ‘B’ final at the second attempt.

“Maybe if we went into Division One, we mightn’t be here today,” says Gillespie.

By the following summer, they’d overtaken St Eunan’s. The underage trained January to October, twice during the week and then all-day Saturday in their various blocks.

When the sides met at the championship quarter-final stage, they drew in Magheragallon before Gaoth Dobhair went into the lion’s den and won in Letterkenny. St Eunan’s never beat them again, and that team went on to win the Ulster U21 title and backbones the senior team that claimed the Seamus McFerran Cup two-and-a-half months ago now.

Repetition was the soul of it. He had a mind for a running game and the tools were at his disposal, so he set about perfection. Tom Beag Gillespie’s training sessions are famed for their intensity and their length, times stretching to three hours.

“Tom Beag used to bring us down, there’d be no footballs and he’d just run us, run us into the ground so we’re used to it,” Naoise Ó Baoill told The Irish News before the Ulster final.

Good, old-fashioned hard work wrapped in a shroud of pride in your part of the world. To build footballers, but to build young Irishmen too, who knew their language, who loved their culture and who felt drawn to home by it.

That was the dream, as much as any trophy.

*****

“The pitch is short so the kicking position is roughly five metres behind the fifty-metre mark. The command comes ‘LEFT!’ He draws back and feels the swing. Another kick and he never even feels the leather on his foot. It is still rising when it clears the posts and the goalstop.”

A passage from ‘This Is Our Year’, Declan Bogue

THE week that Donegal played Kildare in the 2011 All-Ireland quarter-final, Kevin Cassidy begged Jim McGuinness to give him a night off training.

He wanted to go back to his roots and find the right headspace. McGuinness, after much pleading, relented. Cassidy got on to Tom Beag and they met down at the pitch.

Over the years, the pair of them had covered every conceivable angle a football pitch could offer. Gillespie would deliver the ball and, when the breaks came, he’d deliver the critique.

So as Cassidy sat back in the pocket, 50 yards out on the wrong side facing into Hill 16, there was nothing new in what he did when the ball came his way.

Same as a few weeks previous when he’d scooped the ball up heading away from goal, just beneath the Gerry Arthurs Stand in Clones. With barely a glance, he landed a score Donegal so badly needed just before half-time against Tyrone.

These grand stages were just the public getting to see what had been done at home over and over and over again.

“I’d say I did that with Tom Beag maybe 1,000 times, no joke, over the course of three or four years. It wasn’t that I wasn’t used to it,” says Cassidy.

“He’s got terrible patience. Your legs would be hanging off you and he’d say ’10 more’. It was never about him. He wasn’t the one going to be playing in Croke Park or kicking a score, but he still had that passion for it. He wanted to see you do your best.

“Even at this stage, I can see him from my house and he’s always down with somebody. It could be an under-12 player or one of the under-21s. He’s at our club every day.

“If you drive down today, he’ll be at the club somewhere. That’s all he does, all he knows. He played quite a bit himself and when he finished up, he took to coaching teams.

“He really just focuses on the basics. There’s no magic wand with him. It’s kicking with both feet, soloing with both feet, and he’s developed that in all those lads since they were 12 years of age.

“I’ve met him in Croke Park a few times recently when I’ve maybe been commentating and he’s sitting watching the Dublin warm-up, seeing if he can pick anything up. He’s always learning.

“I heard he got two buses and stayed overnight to go to some coaching thing in Down recently. That’s just the way he is.”

The pride coursed through Tom Beag Gillespie when he stood among the crowd in Carrickfinn Airport in October that year to welcome Cassidy home with his Allstar award, the club’s first.

And even though he was filled with the same pride to see the McGees bring Sam Maguire home the following year, it still hurt him to his core to see the man now leading the Gaoth Dobhair charge from full-forward miss out on the All-Ireland.

“It was hard, now. People weren’t pleased with what happened Kevin. Himself, he felt bad about it. It was… it was a hard blow for him, and the people of the parish. It took him a couple of years I’d say to get over that,” says Tom Beag.

But there are far tougher times in the grand scheme. The last few weeks in Gaoth Dobhair have been sombre as they come to terms with the loss of Michéal Roarty, one of four young men killed in a tragic car accident last month.

“He was a very nice fella, a real good footballer. It’s a huge loss to the area, but the families are left with it.”

In that moment, a sadness draws across his face. The children of Gaoth Dobhair clearly hold a special place in his heart, and he in theirs.

There aren’t many Tom Beag Gillespies left.

Bídis gar do do chroí.

'Cherish them'.