BY the time Barry Owens applied to get into St Michael’s Enniskillen at the end of his primary school days, he was already football on the brain.

His father John and uncle Seamus on that side were good footballers, while his mother Rosemary’s brother Paul McKenna was corner-forward on the Fermanagh side that reached the Ulster final in 1982, and their other siblings Damien and Raymond were mainstays of the Kinawley team for years.

The young Barry was down at Teemore “wrecking people’s heads from I was 6 or 7”, out at under-12 training in the days when that was the youngest age group for organised football.

Declan Maguire was a big figure in his young life, a teacher in Teemore Primary School from just outside neighbouring Ballyconnell who took all the youngsters for football at lunchtime and after school.

It was the greatest of thrills when himself and Ciaran O’Reilly were selected to play in Croke Park at half-time in the famous 1993 All-Ireland semi-final between Derry and Dublin.

Every day he kicked ball with his brother Sean off the side of the house and every single Saturday, the two boys and their three sisters went to visit his grandparents, where they went up against the uncles.

“We always went to my grandfathers on a Saturday, my mother and my granny went into Enniskillen, and we’d always have been kicking football there.

“There were only really me and my four siblings, and only two other cousins the same age.”

More have come behind and there’s plenty of promise showing. Lorcan McKenna and Aaron Tierney, both on his mother’s side, are on this year’s Fermanagh under-17 panel.

Their coaches will perhaps recognise the roots of the tree in the way Dominic Corrigan did Barry Owens’.

He achieved a B1 in his 11-plus but such were the application levels at St Michael’s that he had to sit an internal exam. He didn’t get in and ended up at St Aidan’s instead.

The books were never a particular interest.

“I was 15 and we had our English Lit in fourth year. We had a test the name day and I was away watching a junior match. I remember Oisin Quinn – who’d be Peter’s son – saying to me ‘how’s exams going?’ and I said I had one tomorrow. ‘You’re doing some revising,’ he said. I managed to get a B in that, I don’t know how.”

There was enough natural inclination there to get by his GCSEs and in through the doors of St Michael’s at the second attempt five years later.

In his two years there under Corrigan’s wing, Owens would win one MacRory and lose another final during the school’s most prolific spell, where they reached four consecutive finals between 1999 and 2002.

He went in at the same time as Marty McGrath, who was on the Fermanagh minor panel at 16 and whose stars already looked aligned for the success that he would go on to achieve, joining Owens on that Allstar roll in 2004.

Colm Bradley was there too, sharpening the skills that would see him lead the line for years to come.

Owens, though?

“He wasn’t on the radar much, no,” admits Corrigan, who quickly discovered his pedigree nonetheless. He had played with the McKennas during the 80s for club and county.

While Barry Owens walked into the halls of the school without a lofty reputation, he certainly didn’t go back out them the same way.

He’d played most of his club football at midfield or centre-back but in a 13-a-side minor final against Devenish, he made the fledgling steps into the number three shirt.

“We’d played Devenish in the league, we scored 2-23 and they scored 8-8 or something ridiculous. They had a real dangerous lad Gareth Gallagher at full-forward, and they moved me in from centre-half.

“We won the final. I don’t think we conceded a goal.”

In the early days at St Michael’s, he was centre-back on the ‘B’ team in the O’Doherty Cup. But when the starting MacRory full-back went on holiday, he got him his chance in a group game.

He excelled over the two years, and Corrigan’s most sparkling recollection of the magic dust he’d uncovered was in his battle with Michael Walsh in the 2000 series.

“Michael Walsh was the big name in colleges football at the time, he was a fantastic footballer, virtually unmarkable in colleges football.

“Barry and him had great battles and, not being disrespectful to Michael, Barry would have come out the better in them. That’s when I felt, on the provincial stage, Barry Owens made his mark, in those MacRory Cup battles.

“He was always known as a good defender, he had that height, a safe pair of hands and great positional sense. Often times you said to yourself you’re wasting him in there, because he had this massive drive.

“A couple of big steps from Barry would take him from centre-half back to the top of the ‘D’. He was a massive player at number six as well, a great man to drive with the ball because when he went, it was straight lines he went in.

“He didn’t go sideways or go the roundabout. He was outstanding in both positions. You’d have loved to have a Barry Owens at three and six.”

Owens’ own recollection is typically more modest.

“We played them in the first game and I was put on Ronan Sexton first of all, and he was too quick for me. I went on to Walsh and Caroline’s cousin Niall Cunningham went on to Sexton.

“I’d a good enough game on him the first day and went on him in the replay. It just sort of happened. That’s what happens when you get a runaround.”

There was a Hogan Cup sitting there off the back of their ’99 success but an early injury for captain and key defender Ciaran Smith, and a handful of controversial refereeing decisions, let Good Counsel New Ross slip through en-route to beating a softened powerhouse in St Jarlath’s Tuam in the final.

“We’d played St Jarlath’s in a challenge game earlier in the year and had beaten them comfortably, so we knew we were on the right path. There was a bit of controversy about a couple of points, I remember the referee having to be escorted off.”

It was a fantastic four years for the school and it did produce half a dozen players for the county side that would dip their toes in unchartered waters over the next decade.

*******

WHEN he left school he went to BIFHE. The love affair with Belfast lasted until the first instalment of his loan ran out. Quit his course, back down home to the widespread arms that Sean Quinn threw around the community.

He did like so many locals and went to Quinn’s for a job at 19, and he’s been there ever since, operating now as a maintenance engineer. The doorstep of home is always where he’s been most comfortable.

He had been a Fermanagh minor and with Dominic Corrigan’s watchful eye having joined John Maughan’s backroom team, it wasn’t long until the call came to join the senior setup.

Barry Owens made his debut in the ‘B’ championship against Tipperary in 2000, but between his flirtation with Belfast and his club’s good run in his last year of minor, the flame took a while to light.

“We were training with the club and I was up in college, and I just couldn’t be arsed with it. Even then, there was a lot of training and I just wanted to play with the club for a while and try and do best we could with that.

“Plus going on the under-21s, I was training with them anyway. I probably didn’t realise what could have happened.

“I was lucky enough Maughan persisted with me. He’d have been at under-21 matches and there would have been league games the day after, and he’d have been asking me to go to them.”

So he went. And then he went again. Before he knew it, this was part of the routine of his life which stayed part, through thick and thin, for 13 years.

By that stage, he’d been as good as his word and more:

“I’d never turn my back on my county until I know I’m clean f*****”

At 32, with heart surgery and its lasting effects, two cruciate ligament injuries, a bad shoulder and any number of other bumps and scrapes along the way, he knew time had come at that level, but not before he’d left every drop he had.

He and wife Caroline had become parents to twins Shea and Ava on December 16, 2013. He took the league off to adjust and decide whether he would go back.

Getting an hour or two’s sleep at a time in the early weeks wasn’t conducive to the lifestyle now demanded by inter-county football. Yet even though he knew in his heart of hearts, he still couldn’t ignore the call.

“I was 32. I knew myself. I probably should have retired a couple of years before that. I just knew myself I couldn’t do it again.

“Even the thought of the training didn’t appeal to me, going out training two or three nights a week and then in doing weights, it wasn’t for me, not at my age.

“I remember [Pete] McGrath ringing me a couple of times seeing when I’d come back out after the twins were born. I think I wanted to, I didn’t want to let him down.

“I gave it a go but I knew then it just wasn’t in me. The last game was Laois. We probably should have won that game too.

“They were talking after the game, Pete was on about regrouping after a few weeks and going again next year. I just got up and said ‘that’s me for county football; I don’t think I can do it any more. Yous are a great bunch of lads, well fit to win Ulster, go out and win it.’”

And with that, the most decorated individual ever to wear a Fermanagh jersey set off down the long corridor beneath the O’Moore Park stand, on to the bus and away into the past.

But never to be forgotten.

*******

HIS first championship season saw Fermanagh play four games, and three of them were in the space of five weeks against Donegal.

The Ernemen got the better of the first act after a replay but then having been beaten by Monaghan, they had just six days to lift themselves again.

Owens came on in the first three and then started the fourth against the Tír Chonaill side, only to be withdrawn because of injury after just 17 minutes.

The chalk was replaced by the cheese soon after when drill sergeant Maughan stepped down and Corrigan stepped up to take sole charge.

With Paddy McGuinness such a brilliant custodian of the number three shirt, he and Owens alternated between corner-back and full-back in 2002. They roomed together on several occasions and their defensive similarities gave the team a solid footing.

But when Kerry tore them apart in Portlaoise that summer, “a day when romantic ambition met ruthless efficiency” as one scribe put it, McGuinness stepped off the scene, leaving the number three jersey bare.

Some would say that even though he won his Allstars in ’04 and ’06, that ‘03 season where he took sole responsibility for the edge of the square was right up there.

Some would also say Fermanagh would have been in an All-Ireland final had it not been for the injury that forced him off at half-time in the semi-final replay against Mayo.

Rory Gallagher, Raymond Gallagher, Paul Brewster, Neil Cox and Mickey Lilley were among those that left gaps at the end of ’03 as Charlie Mulgrew took over to try and rebuild their shattered confidence.

The stock was replenished with the youth of Eamon Maguire, of Mark Little, of Niall Bogue. They had to fight off rumours of unrest a few weeks before Ulster began and while Tyrone did account for them, their performance was enough to give them heart for a run through the back door.

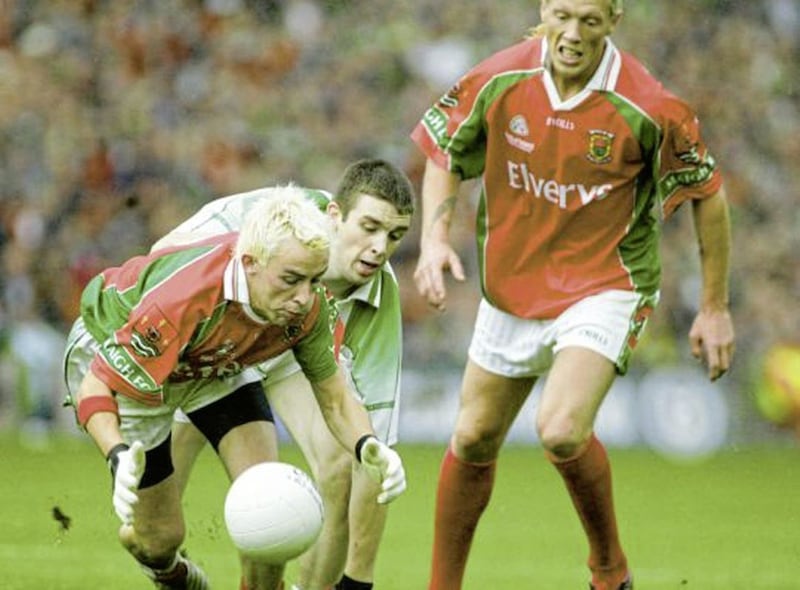

Teemore’s finest held off Joe Sheridan, Colin Corkery, Adrian Sweeney, Ronan Clarke and then Trevor Mortimer on his way to the personal recognition that November brought.

That despite having struggled with the groin against Tyrone and then an ankle ligament injury that hampered him against Meath. The two-week break after that allowed time to settle and from there, things went well until two days after drawing with Mayo.

“We trained on the Tuesday night. I felt the pain in it, I passed no remarks because it didn’t feel too bad. But the first half of the second match, I just found I couldn’t sprint that hard with the pain in it.

“I got through to half-time, they said they’d give me an injection and see how it was, but I tried it in the warm-up area and it was still the same, so they had to replace me.

“What can you do? Try and stay on and not be 100 per cent, or get some lad that is 100 per cent on that could make a difference? It wasn’t to be.”

Mortimer was the one who fisted the equaliser as the dying minutes rolled around in that replay. Mayo went on to kick the last two scores to deny a county that’s never won an Ulster title a place in the All-Ireland final.

It just wasn’t to be.

*******

In Monday’s Irish News: 2008 was all set up to be a big year for Barry Owens – new house, wedding and a Fermanagh team just coming to the boil in their pursuit of that elusive crown. Even open-heart surgery at the turn of the year wouldn’t derail the plans completely, recovering to score one of the most famous goals in the county’s history, but there would be injury disaster to follow…