“F**k away off you black Fenian bastard”

IMAGINE, just for one second, hearing those words on a Saturday afternoon out at your local soccer club.

Imagine standing next to or near the person from whom the bile is being spewed. Maybe you know him, maybe you don't. What do you do?

Maybe you've found yourself in that position before – what did you say?

Anything?

Nothing?

Imagine you are the referee, standing yards away, listening on as every single syllable is spat forth but pretending as though nothing is happening.

Imagine you are one of the other 21 players on the pitch as the abuse persists. Or among the subs warming up nearby. This is a team-mate, after all. A friend. What do you do?

Anything?

Nothing?

Imagine you are the man delivering the diatribe, rabidly staring into the eyes of another human being from the far side of the wire, firing out whatever disgusting insults first reach your lips.

To your right stands your son, a boy of six or seven who hangs on your every word, who idolises you, wants to be just like you. He follows your lead to the letter.

"F**k away off you black Fenian bastard”

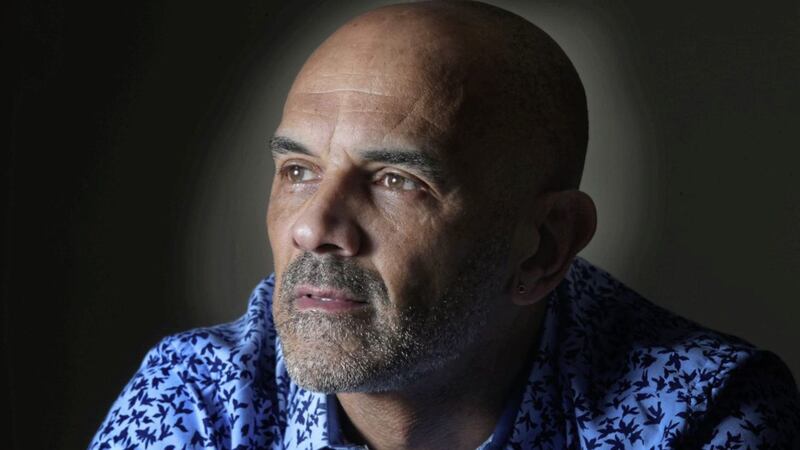

Joey Cunningham thought he had reached the stage where nothing could shock him, but he was wrong.

Quite apart from being one of the very few black players plying his trade in the Irish League during the late 1980s/early '90s, there was plenty more besides that made Cunningham the easiest of targets for terrace taunts at grounds across the north.

First of all he was a Catholic living in the south Armagh village of Crossmaglen, an IRA stronghold reluctantly living under the shadow of the British Army.

With the Troubles still raging, you can imagine how that might have gone down among some of the patrons at Windsor Park. At Seaview. At Mourneview Park. At Shamrock Park even, had he not been wearing the beloved red of the home faithful.

Then there was his GAA background. Raised in Forkhill, just up the road from Cross where he has lived with wife Siobhan since he was 21, Cunningham had been making a name for himself with club and county long before setting foot on a soccer pitch.

Indeed by then he had already blazed a trail, becoming the first player of mixed race to grace the hallowed turf of Croke Park when he featured in Armagh’s National League quarter-final defeat of Carlow on March 3, 1985 - over a decade before Jason Sherlock, son of an Irish mother and a Hong Kong father, so famously burst onto the same stage with the Dubs.

Aged just 18 at the time, this was still a couple of years before Cunningham would pull on a Newry Town jersey for the first time, never mind catching the eye of Portadown boss Ronnie McFall.

The final reason he attracted such negative attention, and perhaps most galling of all for opposition supporters, was his absolute brilliance with a ball at his feet.

For a time, when the Ports were lording it over all and sundry, he was the most dangerous player in the league. In a team not short on star turns, Cunningham’s pace and poise often made him the most exhilarating performer on show, no matter which ground he graced.

The monkey chants? The bananas? The naked sectarianism? It came with the territory - simple as that.

It didn’t happen all the time, far from it, and it didn’t happen everywhere. But when it did, he learnt to let it wash over him. Whatever he picked out was banked and used as fuel to his fire.

Yet almost 30 years on, that spring day at Seaview has stayed with him. The faces of the father and son as clear today as they were when stood just yards away.

"F**k away off you black Fenian bastard”

Joey Cunningham doesn’t have to imagine what it’s like to be the person those words were directed at.

“I went to take a throw-in but we were waiting because somebody was receiving treatment. This fella was behind me and he was giving me dog’s abuse, and he just kept going.

“I’ll never forget the bitterness in that man’s face and I’ll never forget looking around and seeing his son with him, and he was giving me the same abuse.

“I wasn’t even looking at the father now, I was just looking at the son trying to imagine how anybody could bring up a child to have that level of hate towards anybody. He didn't even know what it was he was saying.

“Here was a kid who was abusing me and he didn’t even know what was coming out of his mouth. It was just insane but it didn’t make me bitter at all, it made me sad - sad to think that man didn’t know me from Adam but he jumped on the bandwagon anyway.

“And then the son, this little boy of only six or seven, had been thrown on the bandwagon too, whether he liked it or not.”

It was a long way from the sheltered life led during the free-spirited formative years spent around Forkhill, when kicking ball at the field with friends was all that mattered, the evening dimming of the summer sun the only enemy they had.

Yet, even in the midst of that idyllic upbringing, Joey Cunningham always knew he was different. Not because anybody sat him down and told him. Not because anybody called him names or singled him out in any way.

He just knew.

******************

APRIL 28,1966 - in a London hospital, a baby is born to a young woman from Banbridge, Sarah Faloon. Inside 12 months mother and infant are back in Ireland. Shortly after that Sarah marries Liam Cunningham, moves to Forkhill and the rest, as they say, is history.

Except for the questions. From curious people as he grew older, from his children, Aaron and Niamh, later in life. From himself.

Nowadays, the 51-year-old is an open book but there was a time when such inquiries were unwelcome, primarily out of a fierce sense of loyalty to his dad.

“I have no interest, never did,” he says when asked if any attempt was ever made to contact his biological father.

“I think he was African but I wouldn’t even ask my mother. My dad is Liam Cunningham who I love and adore and he’s just the be all and end all for me.

“It must’ve been hard for dad, mum bringing home a dark kid, but he’s just a brilliant man. He’s unbelievable. To this day I can still see us in the back yard of our house - 9 Fairview Park, Forkhill - just playing away with a ball.

“You couldn't have asked for any more.”

A smile beams from ear to ear as he allows his mind to drift momentarily.

“If I had to do it again, I couldn’t have picked a better place to grow up in.

“Now, even then I was aware that I wasn't the same as all my friends. It’s just an in-built thing. You look different, you know that, but nobody growing up in Forkhill ever treated me any different. I mean nobody. Never ever.”

The first time Cunningham was exposed to the harsh realities of the outside world, and of 1970s Ireland, was when he started secondary school in Crossmaglen.

“People there might have heard of you but they wouldn’t have been used to seeing you, and they would have been looking at you differently I suppose.

“They’d have been over feeling your hair because I used to have an afro. That didn’t bother me – I thought it was great, I really did. With most people, there wasn’t a bother. I was aware from young this was the way it is.

“You know, everybody wants to be liked. I never set out to be different. In actual fact, it was something that probably held me back until later on...”

Because being different, as he soon realised, would often make him a target. That he was small and light of frame served only to raise the bounty on his head.

Cunningham recalls one occasion when he scored twice in an underage soccer match for Dundalk Youths in Finglas before being set upon by four opposition players.

“They kicked the crap out of me in the middle of the game,” he says, smiling at the sheer ridiculousness of the situation in which he had found himself.

“You know, it didn't pay for me to try and be better than anybody else because that just brought more attention on to me - there was enough attention already because of how I looked.

“Here was this wee dark guy who stood out with the big afro, you couldn’t bloody miss me. So I’m thinking ‘Jesus Christ, is that bad enough without going and starting trying to nutmeg people?’”

Such treatment wasn't exclusive to the soccer pitch either.

Already a part of the Forkhill senior team by the age of 17, the lower divisions of Armagh football would prove to be no country for young men in the early ‘80s.

“I’d a man who broke all my back teeth because I was young, I was different and he could do it and get away with it.

“I was maybe 17 or 18, he was a lot older, and I know all his team-mates were disgusted with him. Fifteen years or so later I bumped into him and he apologised in a round-about sort of a way.

“You know why he apologised?” asks Cunningham, the answer already on the tip of his tongue before the question is even out.

“Because it was probably eating him up to think of what he did. He was a coward. What kind of a grown man does that to a kid?

“I’m thinking to myself, you’re going to grow up with sons. Am I going to wait in the long grass, an old man playing B division football and do the same to your son? Of course not.

“It was pathetic.”

Undeterred, it wasn't long before Armagh took notice of the will-o-the-wisp corner-forward starring for Peadar O Doirnin's and Cunningham first arrived on the scene in 1984 after helping the county minors to an Ulster final.

“We weren’t going particularly that well at the time and Joey was only a lad when he came in,” recalls county team-mate Brian Canavan.

“You’d have known who he was alright but you wouldn’t really have passed any remarks; all you were interested in was the fact he could play football and maybe make the team better.

“And right away you could see the talent he had – very fast, very sharp. Back in the day they’d have played small corner-forwards off the big full-forward and Joey was perfect for that role because he had such great pace.”

Armagh reached the National League final in Croke Park the following year, with Cunningham carving out his own niche in the history books along the way – even if the significance of the occasion largely passed him by.

“I had been told I was the first black person to play there but I never really thought a big lot about it... it just didn’t really register.”

Cunningham was involved in the 1987 Ulster final, and was still around the county scene on and off for the two years after but, as his burgeoning soccer career started to take flight, appearances in Armagh colours became more and more fleeting.

******************

GOD bless Mickey Tumilty, he just never gave up. With each week that passed, word spread further about the young kid lighting up the Carnbane League.

“You should be playing at a better level than this,” Tumilty, the coach of Ballybot United, would say at the end of every game without fail.

But Cunningham was happy, and that was all that mattered. There were no great ambitions to rise through the ranks and make a name for himself. No lingering dreams of a possible move across the water.

Keep the head down, have fun and you’ll be grand, he thought. But Tumilty wouldn’t let up.

“I was with Ballybot because of Mickey Tumilty, a man who I had the height of respect for.

“He would pick me up and bring me to the matches, and he’d be telling me to try and go on to the next level. So eventually I agreed to try out at Newry Town.”

Cunningham was an instant hit at the Showgrounds.

Within weeks of his arrival in the autumn of 1987 Newry had landed the County Antrim Shield, and a string of electrifying performances saw Cunningham become the worst kept secret in the Irish League.

Just five months later he played his last game for the club, but his legacy remains.

“He would be in most supporters’ all-time 11, despite being there for such a short space of time, so that tells you its own story,” says Gareth McCullough, sports editor of the Newry Reporter and a lifelong Newry supporter.

“There was just something about him, about the way he played. My granda, Sam McCullough, used to be chairman of Newry. He lived in the town and a lot of the players would have called to see him from time to time.

“I remember Joey coming out one time when I was there. I was no more than six or seven and Joey Cunningham was kicking the football to me out the back of my granda’s.

“To me, that was like some lad nowadays meeting Cristiano Ronaldo or Lionel Messi. I was completely starstruck.”

Gradually, week on week, scouts from clubs in England and among the upper echelons of the Irish League started to filter through the turnstiles, eager to catch a glimpse of Newry’s most prized possession.

Manchester United were due to send someone over on February 27, 1988 – but no Red Devils representative ended up making the trip across the Irish Sea.

Instead, Cunningham spent that Saturday in bed sucking soup through a straw, his Newry Town career having been brought to an abrupt end seven days earlier by one of the Irish League’s most notorious figures...