FOR a few years, every Saturday was much the same. Talisman, maybe Johnny’s because it was nearby, HMV, McDonald’s, Fred’s, then home on the 79.

A fair bit of this activity centred around the Smithfield area behind Castle Court. Then - and to a lesser extent now (so I’m told) - it was Belfast’s pornography mecca. Apologies to North Street, which had a go, but there was only ever one winner.

Smithfield was the city’s run down but no less seedy Soho equivalent; the place where blacked-out windows and neon signs beckoned well-heeled middle-aged men shiftily looking over their shoulders.

As Paul Flynn might say, they’d be constantly scanning, like Ciaran Kilkenny if he was into that sort of thing, always aware of who, and what, was around.

If you’ve seen the Trigger Happy TV sketch of one such establishment’s millionth customer being greeted by a marching band upon his exit, consider yourself in the picture.

Giggling teenagers would be no strangers to those same spots either, let me tell you, and that is what we were in the early-to-mid ‘90s. Mercifully the peculiar presence of free-flying budgies whistling past – to the owners, if you’re reading this... why? - as Catholic guilt ate away at every fibre of your being ensured those visits were few and far between.

Johnny’s (it may have had a more formal name) was a comic shop inside the Smithfield centre, a curious place where anything from military regalia to second hand computer games to Persian rugs to ninja nunchuks could all be purchased inside a 200 metre radius.

Talisman was another comic shop across the road, something akin to Forbidden Planet, though I can’t help but feel that comparison could offend its former patrons.

Fred’s was on the other side of town.

It was a comic shop too (you are probably noticing a theme), located adjacent to the strange V-shaped car park where Victoria Square now stands - probably near Hollister, though Fred’s could hardly have been further removed from the bottled sale of California soul.

There weren’t too many tans around Fred’s. There weren’t too many beautiful women either. Come to think, there weren’t too many women at all. What it did have was young and not-so-young men with greasy ponytails, band t-shirts and questionable personal hygiene. In the interests of full disclosure, I cannot exempt myself from any of those charges.

Not that I even had much interest in comics; I’d go so far as to say I had none. This was the world of a trench-coated friend, albeit one I was only too happy to inhabit because of the dark corridors that aligned with my entirely unconvincing, and unjustified, teenage angst.

What grabbed me most about Talisman was the film section upstairs. Films were important to me at this time. Still are, I suppose. Quentin Tarantino looked and talked like a guy you would meet in any of those three shops, yet everything he touched turned to cool - Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, Jackie Brown, the Kill Bills, and plenty more in the decades since.

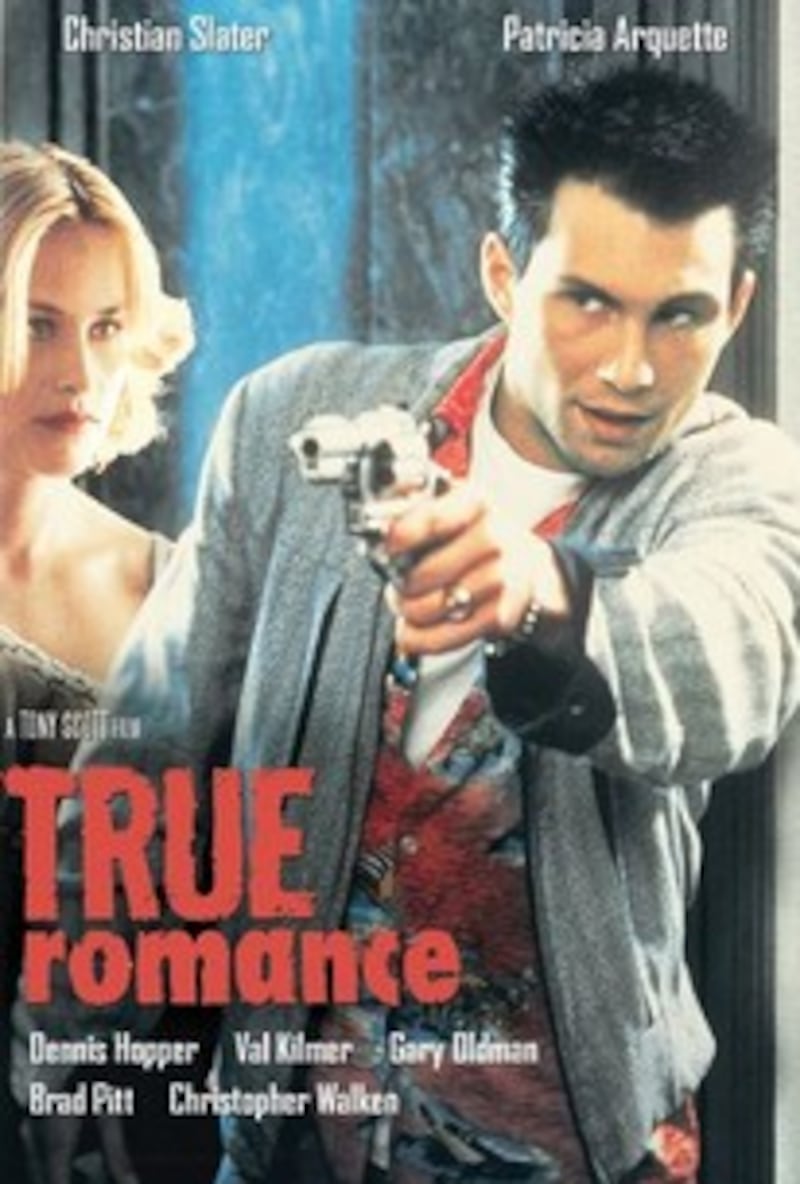

It was in Talisman I first found True Romance. Tarantino had written the script, with Tony Scott – of Top Gun and Beverly Hills Cop fame – the director. From the second that chunky VHS was popped into the two-tonne Ferguson video player at home, I was sold.

There was a bad-ass young Christian Slater, an adorable air-head in Patricia Arquette, Gary Oldman playing a dreadlocked pimp called Drexl, Christopher Walken and Dennis Hopper conjuring one of the greatest scenes of any era, Brad Pitt as a whacked out stoner, James Gandolfini giving a window into the violent future his career held and Val Kilmer as Elvis, only ever appearing in the mirror when main character Clarence was found wrestling with his conscience.

“I like you Clarence,” uh-huh-huh-ed the King, adjusting his sunglasses before a reassuring shot of the finger guns, “always have... always will.”

For years after, I’d have argued the toss with anybody that this was Tarantino’s greatest achievement. I was counter-culturing the counter-culture. Inverting the pyramid. This was microcosm of the macrocosm-type stuff, and I was intensely proud to pioneer such an alternative line of thought, much as I admired his other work.

Then I watched True Romance for the first time in a long time. Years on, I still remembered every line, every pause, every knowing look. What I didn’t remember was that it was actually nowhere near as good as Pulp Fiction or, as it turns out, quite a few films enjoyed since.

The strange silhouetted love scene near the start made me cringe, so too the choreographed slo-mo shootout at the end. Suddenly it all felt way more Tony Scott than Quentin Tarantino.

See, some things are simply of their time; for that reason, they should stay there. During the world’s Covid hiatus, Setanta screened a series of classic GAA games, indulging our lust for nostalgia in the absence of absolutely anything else.

Among them was the epic 1994 Ulster Championship clash between Down and reigning All-Ireland champions Derry. My memories are of being high up in the Celtic Park stand, barely able to see a thing while glorious chaos ensued below.

Other than the widely-shared clips of Ciaran McCabe’s goal and wee James’s point, I could barely tell you a thing about the game. Yet the sounds, the smells, the feeling of the sun beating down and, most importantly, the feelings that day brought are locked in, never to leave.

I recorded the Setanta showing but have never watched it. I don’t want to; I don’t need to. Yet May 29, 1994 crossed my mind while sitting in the stand during Saturday night’s drab Ulster Championship quarter-final clash between Down and Antrim in Newry.

It was the first time I had brought my daughter to a game. Sat on the other side of her was my father, with whom I made that trip to Celtic Park 30 years ago.

She won’t remember the wides, or the unforced errors. She won’t remember that this was a Championship game held in April. She might remember Ryan Johnston’s breathtaking free into the wind, the ball soaring majestically over the sweet spot having started its trajectory half a mile outside the post.

But, even then, I doubt it. She was too busy listening to the woman two rows behind calling Declan Lynch every name under the sun, or tittering away at Andy McEntee’s animated antics on the line.

Sometimes we get so caught up in the minutiae of sport, and what we expect on the way through the turnstiles, that we forget everybody’s experience is their own, regardless of the finer detail of what unfolds on the field.

Maybe it is better left that way.